It wasn’t a Christmas miracle, but I did have a delightful Christmas day surprise this year.

Yesterday, after present-opening and other festivities, I was combing through my grandfather’s war-time letters again (yes, really). As I did so, I realized that the only letters I had ignored were, ironically, the two English-language letters written to my grandfather by Helene (Hank) Gale, the American wife of Opapa’s high school friend George Gale (ie György Gál).

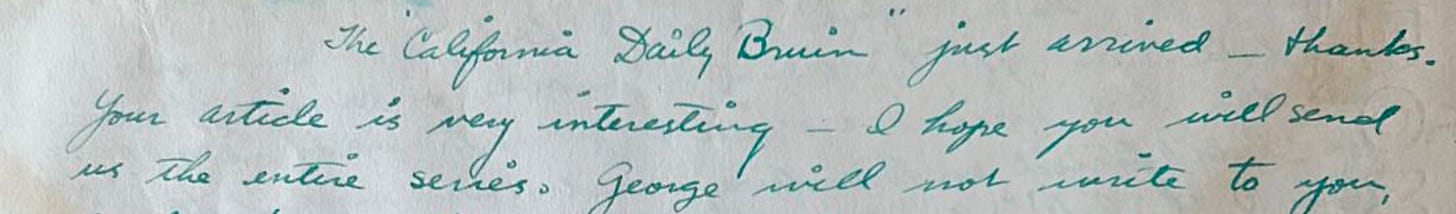

One of the letters included a short postscript. Here it is:

When I saw the words “Daily Bruin,” I did a double take: this was the student newspaper at UCLA. I had recently looked through the Daily Bruin for the years 1940 and 1941, hoping that I might find something written by or about my grandfather. I had searched the text for his name, for the U.C.L.A. International Club, and for a few other terms, but didn’t find anything. I even browsed through some issues, but there were thousands of pages for just 1940 and 1941, so I didn’t read through them all. (You can see the digital files here and here if you’re interested.1)

But now, thanks to this tip from Hank Gale’s letter, I knew there must be something.

I re-opened the digital files for the UCLA Daily Bruin. Hank had started writing her letter on February 19, 1940, and she posted it on March 11, 1940, so his article must have been published between those two dates.

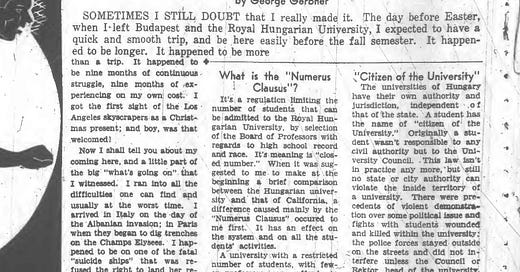

After several minutes of scrolling and scanning, I found it: “15,000 Miles to U.C.L.A: Former Hungarian Student Tells Trip Experiences,” by George Gerbner. My jaw did, actually, drop.

There, before me, were my grandfather’s own descriptions of his 1939 journey from Hungary to the Unites States — the trip I spent several months researching earlier this year. How did this not come up in my previous text searches?! And not only that: this was only the beginning. Three days later, on March 7, 1940, Opapa had published a second installment of his story. Further installments were included throughout March and April. Then he started publishing on other topics: the history of Hungary and Romania from the 19th century to the beginning of the World War; commentaries on fascism; responses to editorials. I have not finished combing through the issues, but so far, I have found about a dozen articles he wrote between 1940 and 1941 for the UCLA Daily Bruin.2

As I read through his first article, much of it was familiar to me: I knew the date he departed, I knew about his journey through Italy and France, I knew about the S.S. Flandre, and his six months traveling in Mexico. But there were many new details: precious details, like how they began to “build trenches on the Champs Elysees” when he arrived in Paris.

Most significantly, I was able to read Opapa’s own narrative about why he left Hungary from the persective of March 1940, just months after he arrived in the US. This was before the full horror of World War II had been revealed; before Germany had invaded France; before millions of Jews had been deported to death camps; before his father was murdered. In March 1940, Opapa’s narrative about his journey was still in its infancy: it contained details he would later forget, and the broad contours of the story would evolve and change over the years — just as the meaning of World War II would change as the horrific events of the next five years came to light.

The most striking thing to me about Opapa’s 1940 narrative is that he never — not once — mentions the word “Jew” or “Jewish” in reference to himself. In fact, the only references to religion in this first post are to (1) Easter, when he departed Budapest, and (2) Christmas, when he arrived in LA: “I got my first sight of the Los Angeles skyscrapers as a Christmas present,” he wrote, “and boy, was that welcomed!” Christian holidays create the narrative bookends for his journey.

Rather than writing about anti-Semitism explicitly, Opapa focused this first article on “Numerus Clausus,” the quota system used at Hungarian universities. Numerus Clausus was intended to limit Jewish matriculation at Hungarian universities, but Opapa doesn’t explain this. Instead, he uses subtle and oblique references to explain how “high school record and race” were the qualifying metrics for admission.

The next section of his article, “Citizen of the University,” goes into more detail about student life at Royal Hungarian University. The University was autonomous, which meant that it had its’ own jurisdiction, “independent of that of the state.” While this might sound nice, in reality it meant that when there were “violent demonstrations” within the bounds of the University and students were “killed,” the police did not intervene.

Again, Opapa didn’t mention specific incidents of “violent demonstrations,” but they were most likely violent demonstrations against Jews. There were so many incidents of anti-Semitism in central European universities that they had become part of life during the interwar period.3

Reading through Opapa’s columns, I wondered about his objective in writing about his experiences for the UCLA Daily Bruin. I see him trying doing a few different things: he was certainly trying to process what happened to him over the previous year; he also wanted to inform American students about events in Hungary and Europe more generally. But at the same time, I see him carefully constructing a narrative about himself. Who did he want to be in this new country, at this new University? What did he want people to know about him, and what did he not want to reveal?

At his high school, his religion had defined his place: he was listed as an “Israelite” in his high school yearbook, and his courses were organized, in part, around Jewish worship services. After high school, the rise of anti-Semitism — including Numerus Clausus — meant that his opportunities were curtailed dramatically during his first year of University.

I think that above all, he wanted to be free from the oppression of anti-Semitism. He wanted to create his own narrative — his own story.

And this is how he chose to begin.

The digital files are even more confusing than I have explained: all of the Daily Bruin newspapers are listed as being published in 1912 (!), so at first I thought there was no digitized version of the newspaper from 1939-1941. After corresponding with the UCLA archivists, they explained that several decades of the Daily Bruin are listed as 1912, but that there are dozens of reels, so you have to find the correct reel for the year. 1939-40 is Reel 19, and 1940-41 is Reel 20.

I’m delighted, but also a bit peeved that I had trusted my initial text searches of the Daily Bruin. As an experiment, I decided to download the entire run of the Daily Bruin from 1940 and 1941 and put it through my own text recognition software, to see if I could get it to turn up anything for my text “Gerbner” would turn up. It took about 7 hours to run the software on the digitized file, but once it was through, I got about 10 hits for “Gerbner.” Upon further inspection, however, I realized that the software was still missing several hits for “Gerbner.” Lesson learned: don’t trust text recognition software!

See, for example, Karády and Nagy, eds., The numerus clausus in Hungary: studies on the first anti-Jewish law and academic anti-semitism in modern Central Europe (2012)

The parallel between the demonstrations on the campus of the Royal Hungarian University and what is presently occurring on many American campuses is so disturbing.

Amazing!