Yesterday, I concluded that Opapa took the S.S. Flandre across the Atlantic when he fled Europe in 1939. The Flandre landed first in Havana, Cuba, and then in Vera Cruz, Mexico, where Opapa disembarked.1

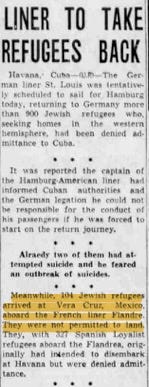

It turns out that the SS Flandre was involved in an international scandal when it arrived in the Caribbean in May 1939. Yesterday, I shared the following news clip from the Minneapolis Star.

As this article notes, there were actually several ships involved in the scandal. On the SS Flandre, “104 Jewish refugees” were “not permitted to land” in either Havana or Vera Cruz. Meanwhile, on the “German liner St. Louis,” there were “900 Jewish refugees” who were “denied admittance to Cuba” and were being transported back to Hamburg. “Two of them had attempted suicide,” the article continued, and the captain feared that there would be “an outbreak of suicides” on his return trip to Germany.

When I read this, I had three main questions:

Why was Opapa able to disembark, when so many other Jewish refugees were not?

Why were the Cuban and Mexican governments refusing entry to Jewish refugees?

What happened to the refugees who were denied entry?

Today, I’ll focus on question #2, specifically on the situation in Cuba. I found a dissertation written on this subject, which offered a very clear explanation of the Cuban situation.2

Here is what happened: In 1939, Cuba was one of the few ports still open to Jewish refugees. In order to enter Cuba, however, the Director of Immigration in Cuba, Manuel Benitez, required refugees to pay a “landing permit” (sort of a bribe) of $150 or more (about $3,300 today).

By spring 1939, however, a few factors had started to change the situation in Cuba:

First, hundreds of Jewish refugees were landing in Havana every month, leading to anti-immigration sentiment.

Second, Nazi propaganda and Cuban fascists were promoting anti-Semitic messages in the newspapers and radio station. They turned the refugee crisis into an anti-Semitic news story.

Finally, Benitez’s “landing permits” - which made Benitez and his allies very rich - became a point of contention within internal Cuban politics, when a rival political faction (represented by President Brú and his party) claimed that they were illegal.

By April 1939, anti-Semitism was on the rise in Cuba, due both to Nazi propaganda and immigration politics. Cuban newspapers were printing numerous anti-Semitic stories, and attacking the newly arrived Jewish refugees as being a drain on the welfare system in Cuba. At the same time, newspapers also started to report on Benitez and the “immigration racket” of charging $150 or more for a “landing fee” that lined the pockets of immigration officials -- and especially Benitez himself.

In response, on May 5, 1939, the Cuban government (run by anti-Benitez President Brú) issued a new decree: no refugees would be allowed to enter Cuba on one of Benitez’s “landing permits.” Only people who had deposited $500 in bonds and held appropriate visas that were approved by the Cuban Secretaries of State, Labor, and Treasury would be admitted into Cuba.

The new decree didn’t explicitly outlaw Jewish immigration, but it made it very difficult — and unobtainable to anyone who could not put up a $500 bond (the equivalent of $10,000 today). Moreover, Benitez’ landing permits — including those that were purchased before the decree — were now void. (94) Despite this, Benitez “continued to assure Jewish refugees through his agents in Europe that his certificates would be honored.” (97)

After the May 5 decree, the Jewish Joint committee (JDC), issued warnings to the European offices in Paris and elsewhere. On May 10, the JDC headquarters cabled Morris Troper (the husband of Ethel Troper, who lent Opapa $232 for his ticket on the Flandre), warning that:

ACCORDING TO NEW REGULATIONS … ADMISSION WILL BE REFUSED TO REFUGEES NOW HOLDING TEMPORARY LANDING PERMITS stop …SUGGEST YOU ADVISE ALL EUROPEAN COMMITTEES NOTIFY REFUGEES NOT TO SAIL UNTIL FURTHER ADVICES stop

Joint Distribution Committee to Morris Troper, “Cable,” May 10, 19393

This cable — addressed to Morris Troper and dated May 10, 1939 — is especially interesting, because Opapa was still in France, and he was in direct communication with Ethel and Morris Troper. It seems very plausible that the Tropers may have warned him about this situation and made sure he had the appropriate paperwork in place before boarding the S.S. Flandre.

When the SS Flandre departed on May 16, 1939, nobody knew what would happen when it arrived in Havana. Members of Joint hoped that they could negotiate a deal with the Cuban President, though they remained anxious.

The first oceanliner to arrive in Cuba after the decree was the S.S. Iberia, the ship that Opapa was supposed to take but was unable to, because it took him too long to secure a visa. The Iberia landed in Cuba the week of May 14, and its Jewish passengers held the now-illegal Benitez landing permits. Fortunately for these passengers, Benitez boarded the ship himself and allowed the refugees to enter the country. President Brú, to “save face,” declared that he would allow this because the ship had departed on April 30 -- before the May 5 decree.

After the Iberia left Havana, however, Benitez resigned as Immigration Commissioner, and he disappeared on a “two-month leave of absence.” During the second half of May, three more ships with Jewish refugees arrived in Havana:

First, on May 27, 1939: the St. Louis, a Hapag ship that sailed from Hamburg with over 900 Jewish refugees.

Second, also on May 27, 1939: the Orduña, a British ship with 120 Jewish refugees

Third, on May 28, 1939: the Flandre, the French oceanliner with 104 Jewish refugees. Opapa was one of the passengers.

Despite the fact that many passengers on these ships had purchased “landing permits” before the May 5 decree, they were denied entry. Cuban President Brú insisted that the ships leave the harbor before he would begin negotiations.

During the negotiations, the St. Louis waited near Miami — so close to shore that friends and relatives could see the passengers. The JDC (Joint) promised to put up $500 bonds for each of the passengers. Despite this, President Brú refused to budge, even though he insisted that he was sympathetic with the plight of the refugees.

So what happened to the refugees on board these ships?

Thanks to the efforts of the Joint Jewish committee — and especially Morris and Ethel Troper — many of the refugees were granted admission to other countries, including Britain, the Netherlands, France, Belgium, and Chile (note, the United States is not on the list).

Unfortunately, many of those countries would fall under Nazi rule the following year, and over 200 Jews, including some who had sailed with Opapa on the SS Flandre, would later die in the Holocaust.

The episode was one of many that demonstrated the lack of international support for persecuted Jews and other refugees at the outbreak of World War II.

Again, Opapa was one of the (very) lucky ones.

***

Nuts to crack:

I still haven’t figured out why the Jewish refugees were turned away at Vera Cruz. Was there a change in policy, similar to Cuba?

I confirmed that Opapa took the Flandre when I found the following passage in one of Opapa’s autobiography drafts:

I had to bribe a Mexican consulate official to give me a visa to Mexico, which was not unusual. I got a passage on the French ship S.S. Flandre (a wonderful small passenger liner) which was, incidentally, sunk in World War II. The only passage open at this time was a first-class passage.

Opapa also answered one of my “nuts to crack,” which was about how he managed to get a Mexican visa in Paris: he bribed the consulate official.

Zhava Litvac Glaser, “Refugees And Relief: The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee And European Jews In Cuba And Shanghai 1938-1943,” CUNY Graduate Center Dissertation, 2015.

Cited in Glaser, “Refugees And Relief: The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee And European Jews In Cuba And Shanghai 1938-1943,” p. 100

My aunt's aunt (still alive and kicking at 100) was on the St. Louis!

And lucky.