It was not easy to escape from Europe in 1939. Oceanliners were full, visas were difficult to obtain, and many countries — including the United States — were refusing entry to Jews fleeing persecution.

As I read through Opapa’s letters from 1939, I realize how lucky he was. He would not have made it to the Unites States without the help of numerous individuals on both sides of the Atlantic ocean.

I’ve always known that Opapa’s half-brother Laci was absolutely essential for his escape. I don’t think my grandfather would have survived the war without his help. And indeed, the letters from 1939 are filled with references to Laci’s “sacrifices” — he put up large amounts of money to help pay for my grandfather’s expenses, despite being out of work himself.

As I read more letters, however, new people emerge from the woodwork: distant relatives who helped Opapa in Paris and Venice; friends who offered advice; and also strangers, who went out of their way to make sure he was able to get a ticket, or get through immigration upon arrival.

Today I want to focus on one of these people, Ethel Dorothy Troper (née Gartner), a Hungarian Jewish woman who was living in Paris in 1939. She starts appearing in Árpád’s letters in April of 1939, a contact of his sister, Józsa Gerbner Bloch.

I did a little digging into Ethel’s life: she was born in Budapest in 1893, so she may have known Józsa growing up — Józsa said that they had a “lovely friendship” in 1939. Józsa would have been a bit older — I believe she was born in the 1880s. But Ethel, unlike Józsa, emigrated to the United States, and she eventually became the Office Manager of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies. In 1919, she married Morris Troper, an American Jew and US Army officer who went on to run an accounting firm.

In 1938, Morris Troper was appointed the chairman of the European Executive Committee of Joint (now known as JDC), a Jewish humanitarian organization, and Ethel moved to Paris with her husband to help coordinate the evacuation of European Jews from Nazi-controlled territories.

In 1939, when Opapa fled Hungary, Józsa urged him to contact Ethel. She gave him Ethel’s address in Paris, and later called Árpád, reiterating her advice and adding, “you can count on this lady one hundred percent.” She and Ethel had a “lovely friendship,” she added.

As it turns out, Opapa desperately needed Ethel’s help. When he arrived in Paris in late April 1939, Opapa had no money and no visa for any destination in the Americas. He didn’t know what Oceanliner he would be able to take. His French visa was only good for two weeks — and getting that visa had been a small miracle in itself.

Ethel Troper is first mentioned in Árpád’s letter from April 12, 1939, though not by name. She is just Józsa’s contact, the “wife of the chairman of Joint.” It’s not until Árpád’s April 27 letter that we learn her name: “Mrs. Troper” had agreed to help with the transfer of funds to pay for Opapa’s ticket. Laci or Árpád would wire money to Ethel Troper, who would help Opapa buy the ticket. But it seems that the money for the ticket didn’t make it to Paris. So instead, Ethel Troper lent Opapa several hundred dollars.

Months later, in July, when Opapa was in Mexico, they were still trying to figure out how to pay Ethel Troper back. Eventually, her name drops out of their correspondence — hopefully because they did successfully repay their loan.

I like this story because it helps to illuminate female networks and labor — stories and connections that so often go unrecorded. Up to this point, I just knew that Opapa went to Paris and that he got on an oceanliner from there. But it wasn’t possible to just walk up to a ticket office and get a ticket: it was extremely difficult to arrange both the oceanliner and the complicated set of visas that Opapa needed to escape Europe and arrive safely in America. Behind the scenes, lots of people were working to help him out — and many of them were women like Ethel Troper and Józsa Gerbner.

It’s difficult to find out information about both Ethel and Józsa. There are no “Ethel Morris” papers. Instead, I have to look through the Morris Troper papers to find references to Ethel — she is there, but she’s never the focus. In order to put her story together, I have to connect all the dots, slowly working out her activities and life story from passing references.

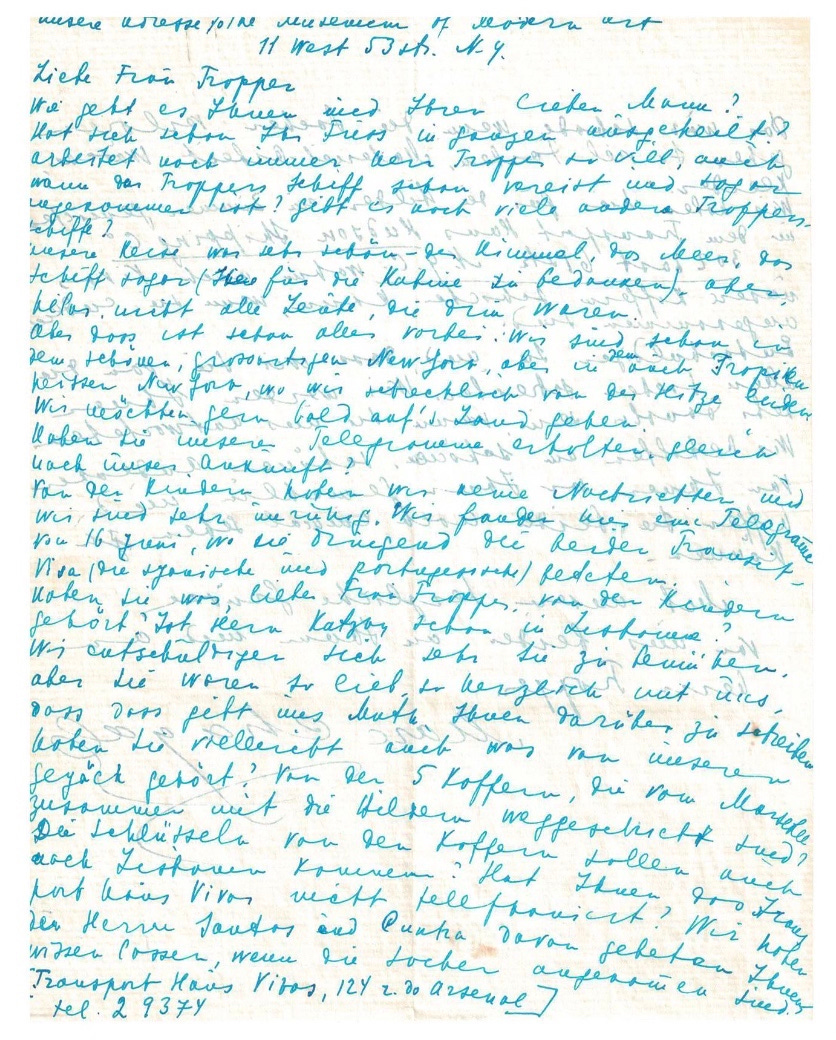

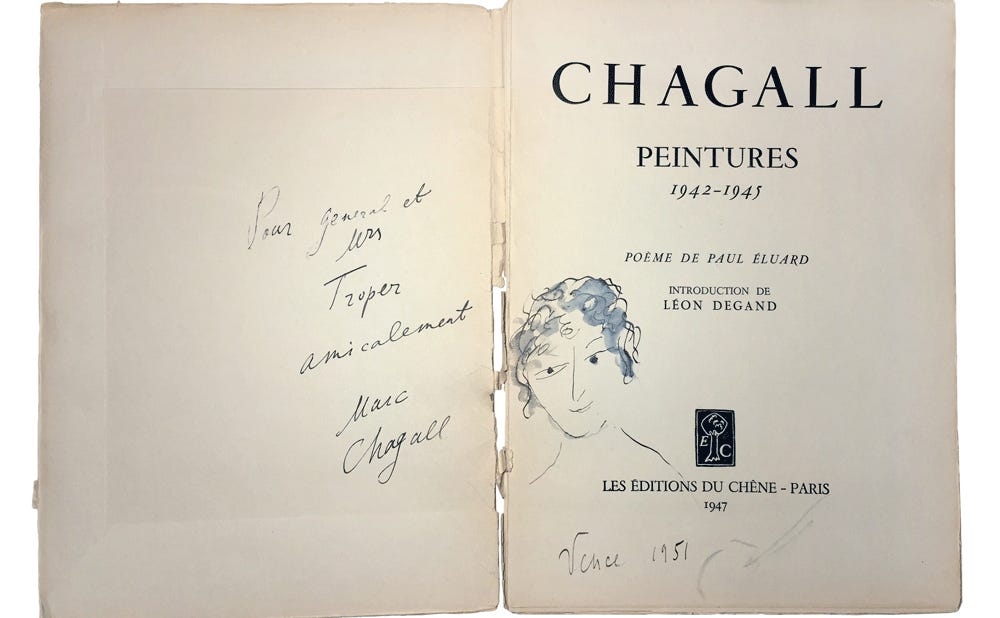

So to end, I want to share another reference I found to Ethel Troper — this one from the French artist Marc Chagall. It turns out that Ethel Troper also helped Chagall — along with his family and artwork — flee Nazi-occupied France. While most references to Chagall mention only “Morris Troper,” Chagall’s own letters sold at auction a few years ago, and several are adressed not to Morris Troper, but to “Frau Troper” — Ethel.

As a gift of thanks, Chagall also inscribed a copy of his Peintures to “general et Mrs Troper.”

***

Nuts to crack:

I can’t seem to get access to the Guernsey auction that sold Chagall’s Holocaust letters. Anyone else have luck?

When exactly was Józsa Gerbner born?

More of a P.S. than a “nut to crack,” but: less than a month after helping Opapa, the Tropers would help to negotiate the resettlement of more than 900 Jews who have been refused entry into both Cuba and the United States on the SS St Louis.

Thank you for your next great post, and for finding these details. I have always wondered who (a Parisian) bought George his ticket. One of the main lessons from Opapa’s stories is that one person’s offer of help can make a difference. Yes, systemic change is needed, and yes, ‘it takes a village’, AND each of us has the power to help and change the course of someone else’s life. He was always grateful to many people -- often unnamed-- who helped him.