Opapa used to tell a story about how he got into University in 1937. It went something like this: he didn’t have very good grades in high school, but he loved literature and folklore. He applied to University, and was rejected.

However, he also managed to win first prize in a national literary competition. After that, the headmaster of his school announced that it was an outrage that the winner of a national competition did not have a place in University. So he changed all of Opapa’s grades to an “A,” and Opapa was eventually admitted.

In Opapa’s story, the main reason he was rejected from University was his grades; the main reason he was admitted was the fact that he won a literary competition, and this then became a rallying cry.

The story is true, but also incomplete.

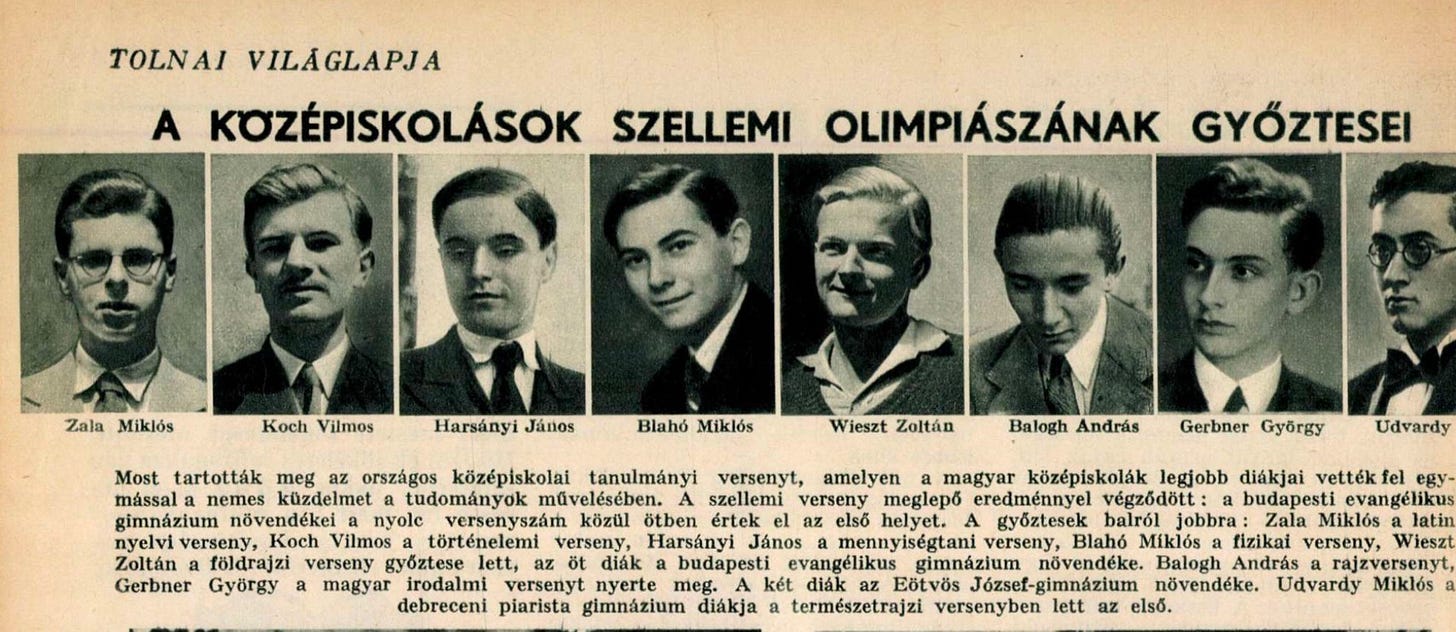

A few weeks ago, as I was scouring the Hungarian-language newspapers, I came across a cache of articles from 1937: the first several announced that Gerbner György was one of the winners of the national literary competition. Between June 4-16 1937, Opapa’s name was mentioned in seven different Hungarian newspapers in connection with the national competition. In this article from June 16, 1937, for example, his photo was printed alongside the other winners.

Then, there was silence for three months: until September 1937.

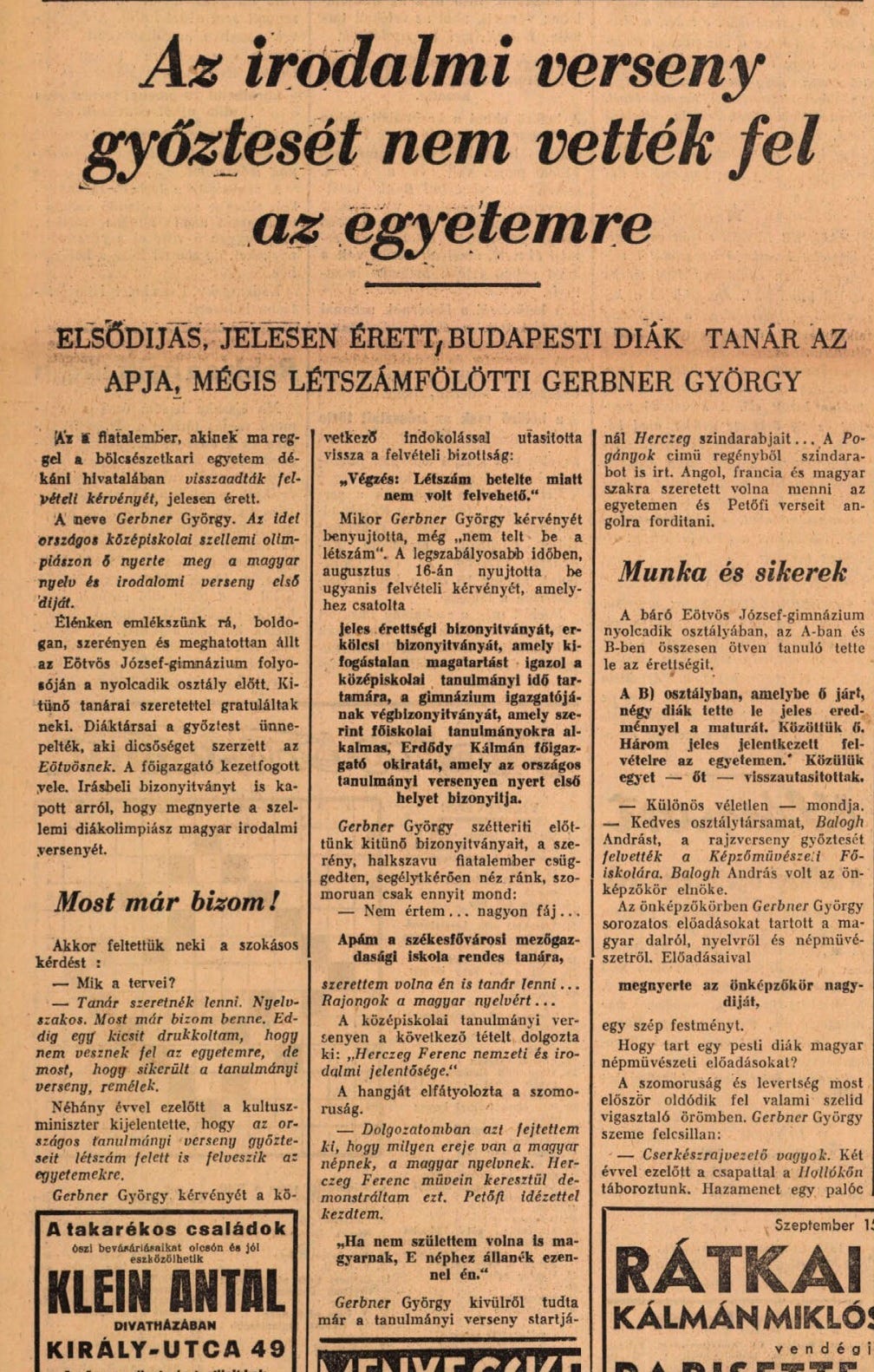

On September 16, 1937, three newspapers published articles about Opapa, and all three expressed outrage that the winner of a national literary competition was rejected from University. Here is one of them:

The headline of this article, which was published in Esti Kurir on September 16, 1937, reads: “The winner of the literary competition was not accepted at university.” The subtitle gets straight to the point:

GERBNER GYÖRGY IS A STUDENT FROM BUDAPEST WITH EXCELLENT GRADUATION GRADES AND A PRIZE-WINNER. HIS FATHER IS A TEACHER, STILL THERE IS NO VACANCY FOR HIM

The article includes an interview with Opapa. The author had visited Eötvös Gimnázium, where Opapa’s “fellow students were celebrating the winner, who had brought glory to the Eötvös. The school principal shook hands with him.”

The journalist then asked Opapa “the usual question”: “What are your plans?”

Opapa replied that he “wanted to become a teacher,” but he was worried that he wouldn’t be able to because was not accepted at University. He had been “hopeful” because he won the national competition. According to the article, “A couple of years ago, the Minister of Education and Religion stated that the winners of the national academic competition would be accepted at university even if there is no vacancy.”

Yet in Opapa’s case, despite the fact that he had won the national competition, he was still rejected due to “no vacancy.” The author clearly thought this was ridiculous:

When Gerbner György submitted his application, there was “no lack of vacancy”. He submitted his enrolment application at a correct date, on August 16. He also enclosed his graduation certificate with excellent grades; his certificate of good conduct proving his impeccable behavior during his high school studies, his final school certificate issued by the school principal stating that is suitable for higher education; a document issued by principal Erdődy Kálmán, verifying his first place at the national academic competition.

The journalist described how Opapa “spread out his excellent certificates for us,” adding that “the modest, soft spoken young man is looking at us discouraged, asking for help. He seems sad and only says: ‘I do not understand… it hurts a lot…’”

The article reiterated Opapa’s accomplishments in great detail: for the literary competition, Opapa wrote about “The national and literary significance of Herczeg Ferenc.” Opapa’s voice was “filled with sadness” as he explained:

In my essay, I was elaborating on the power of the Hungarian nation, the Hungarian language. I was demonstrating this throughout Herczeg Ferenc’s works. I started with a quote from Petőfi.

“Ha nem születtem volna is magyarnak,

E néphez állnék ezennel én.“

[If I was not born Hungarian,

I would join this nation, now]

The author also noted that Opapa “had already learnt Herczeg’s play by heart… He even wrote a play based on the novel Pagans [Pogányok]. He wanted to enroll in the English, French and Hungarian majors at the university and wanted to translate Petőfi’s poems into English”

During the interview, Opapa’s eyes “lit up” when he recounted his work as “head of the scout squad,” and his visits to Rimóc and Hollókő. At University, he hoped to “further develop his scientific studies, [and] his love for the Hungarian people and language.”

The Esti Kurir article, while very sympathetic to Opapa, did not offer a reason for his rejection. Two other articles, however, made some suggestions.

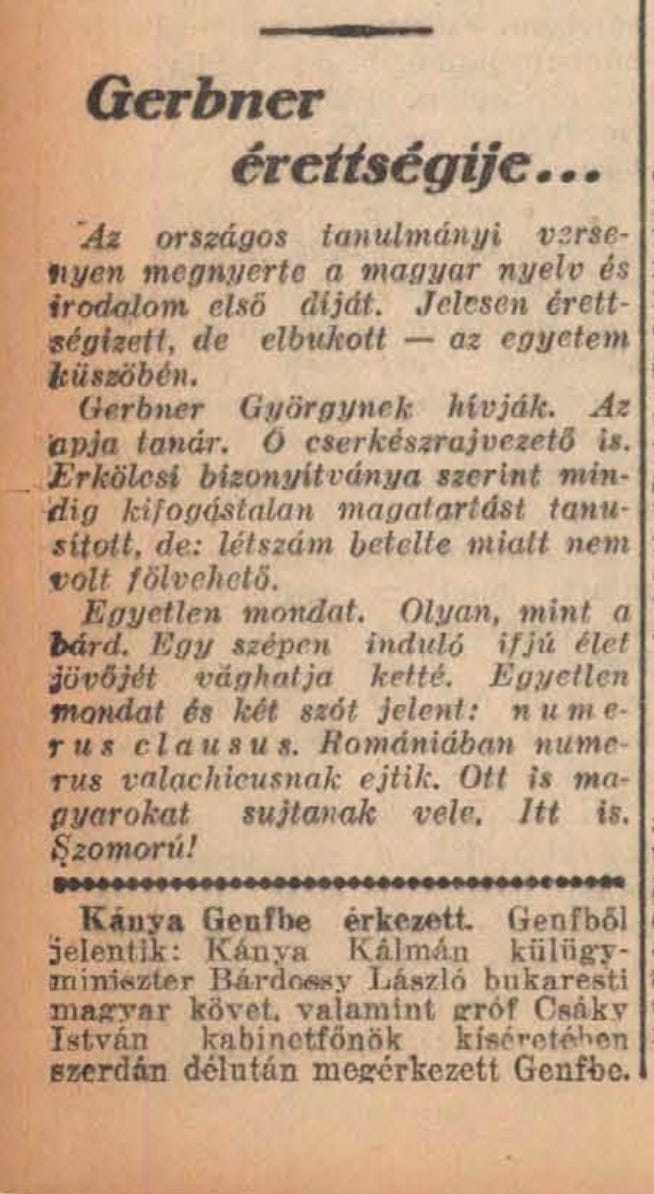

In this short article from Népszava, the author writes that Gerbner György “won the first prize in the Hungarian language and literature at the national study competition. He graduated with honors, but failed — on the threshold of university.”

Why?

“Two words: numerus clausus.”

Hungarians would have known exactly what the author meant by “numerus clausus”: it refers to the quota system. In Hungary, the numerus clausus system was introduced in 1920, and it capped Jewish participation in various industries and institutions at 6%. The law was repealed in 1928, but by the late 1930s, numerus clausus was again becoming more prominent. There was still no “numerus clausus” law, but there would be — in 1938, the following year.

The second article is even more clear about the reason that Opapa was rejected from University. It also suggests that Opapa was not the only victim of bias:

On Wednesday, the news leaked out that Czinczenheim, who won the second prize in the mathematics department of the academic competition, was not accepted at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, where many applicants with honors were rejected. György Gerbner, who won the first prize in the Hungarian language and literature competition, was rejected although this boy's father is also a high school teacher and meets the conditions in all other respects. In the case of György Gerbner, the only factor that could play a role was the fact that he was a young man of Jewish faith, who was cherished in high school and who was certainly praised and feared for his very special talent.

Here, it’s pretty clear: Opapa was rejected because he was Jewish.

Opapa knew this too. In 2004, about a year and a half before he died, he created a word document on his computer and entitled it “My Life.” In this document, he offered a different version of the story than I remember him telling us at the dinner table. According to “My Life,” religious and ethnic prejudice were a well-known component of University admissions in 1930s Budapest:

[E]ntrance into the university…was not only a highly selective procedure but also a prejudicial one, systematically limiting or excluding Jewish and Gypsy applicants.

Yet, he continued, “it so happened that my school sent me, on the basis of a school-wide competition and then a district-wide competition, to a national literary competition.” When he won first prize, “one relatively liberal daily paper also wrote an article about how shameful it was that application of the winner of the national competition was rejected on religious grounds.”

Eventually, the principal of his school intervened:

The principal of our school came to the classroom where the final session of the baccalaureate examination was held and looked at the list of graduating students and said, “They have made a terrible mistake in not recognizing this Gerbner who's so good.” In the presence of everyone, including myself, corrected every one of my grades to an A. That assured my admission to the university, which was otherwise out of my reach on account of the “numerus clausus,” one of the many anti-semitic measures of the time. It's one of the series of “accidents” that in many ways provided turning points for my life.

This version of the story is exactly like the one I remember Opapa telling — except that in this one, Opapa writes explicitly about “numerus clausus” and anti-Semitism — these, of course, were the real reason he was not admitted to University.

It all makes sense: Opapa never talked about how he was Jewish, so why would he include “numerus clausus” in the story he told about his admission to University? I don’t fault Opapa for wanting to leave both anti-Semitism and Judaism behind him in Hungary. But it’s interesting that when Opapa sat down at his computer in 2004, at age 85, he decided to change the story again — to re-introduce the reality of anti-Semitism into the story of his life.

Perhaps he decided, after many years of censoring his own life story, that he wanted the truth to be known. Maybe he wasn’t ready to tell this version at the dinner table, but he chose to record it on his computer. The document he created, “My Life,” was not finished, but I think it’s a story he wanted us to know.

For if Opapa believed in anything, it was the power of stories.

I see I never commented on this post. I meant to but got distracted. Of course I got the same version as you of how he got admitted to the university (without the being Jewish component, just that his grades weren't that great so the Principal changed them to A's). As I think I told you, he told me that he was Jewish the summer after my freshman year in college. But even then he didn't indicate that that was the reason he was initially not accepted to the University.