Today, we are going back in time — to the summer 1936, the summer that Opapa turned seventeen. The summer of 1936 was, in Opapa’s words, “sensational.” It was better than any other summer, “better than any vacation” he’d gone on before.

Now, what do you think the *best summer ever* might entail for a seventeen-year-old boy? If you’re thinking romance ala “Grease” the musical (ie: “Summer Loving”), you’re wrong.

In true Opapa fashion, the best summer ever meant that Opapa got to live in a remote Hungarian village, working the fields with the local Palóc people, and learning about Hungarian folklore and dancing.

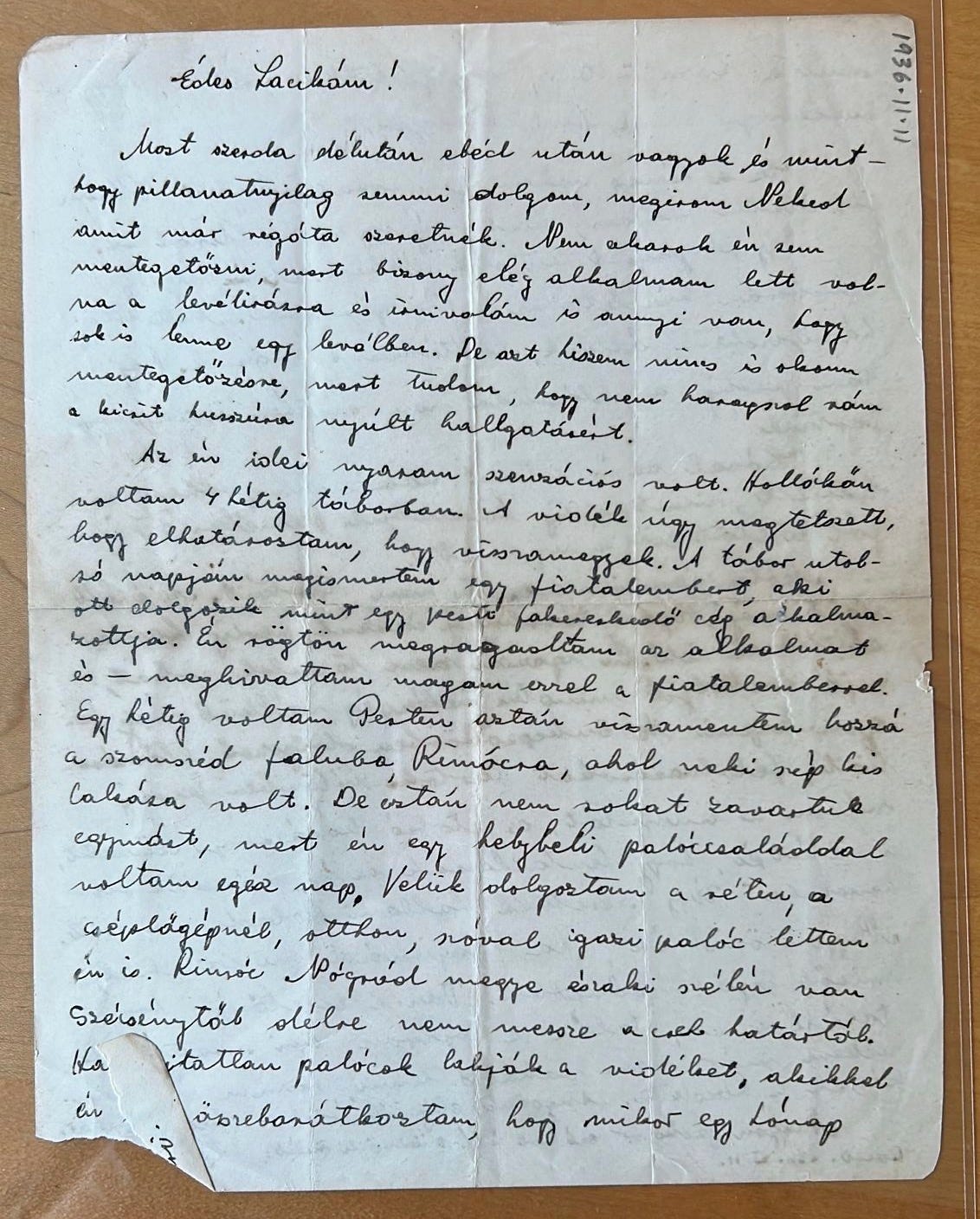

Opapa described his summer in a lovely letter to his half-brother Laci, who was living in Los Angeles. Here is the original letter:

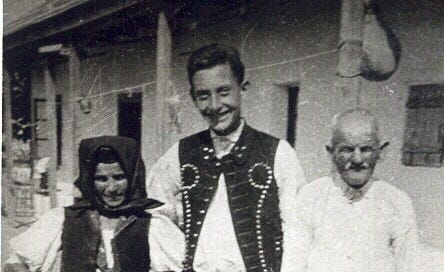

Opapa wrote that he went to camp in Hollókő for a month. Hollókő, a village in northern Hungary, is now listed as a UNESCO heritage site (as of 1987). I think Opapa spent most of his time in the countryside, near the village. I am pretty sure he was at a Scouts camp, though I am not 100% sure. I found a few photos on Opapa’s computer that are probably from the summer of 1936, and he had titled them “Scout1,” “Scout2,” and “Scout3.” This one is “Scout3”:

Opapa “got to like the area so much” that he “decided to go back.” On the last day of camping, Opapa met a young man who was from a village in northern Hungary, but worked “as an employee of a wood trading company in Pest.” Opapa immediately “seized the opportunity” and managed to get himself invited to the young man’s home in Rimóc, the neighboring town.

Rimóc, he wrote to Laci, “is located at the North part of Nógrád county, South to Szécsény, not far from the Czech border.” The region is home to the “Palóc people,” ethnic Hungarians who have distinctive dialect, dress, and customs.

After a week back home in Budapest, Opapa returned to Rimóc. This time, he lived with a local Palóc family in Rimóc. He saw his friend occasionally, but spent most of his time with the Palóc family, “working with them at the fields, by the threshing machine, [and] at home.”

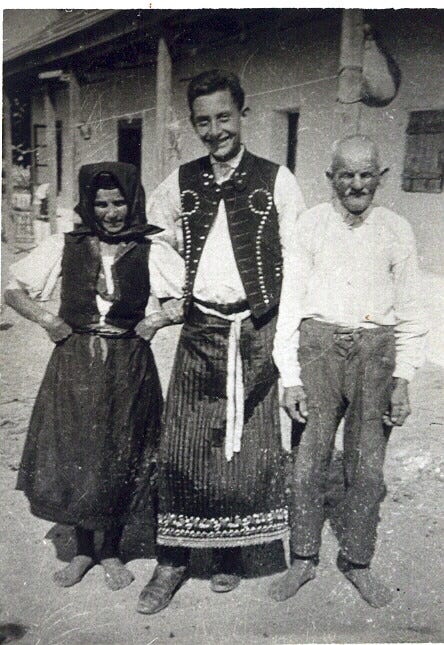

“I became a real Palóc myself,” Opapa wrote, and “after one month, they made me promise to return during the vacation at Christmas.” Opapa included a photo with his letter to Laci: “My young friend took this picture with my little camera,” he wrote. “My hosts are standing beside me, with their house in the background. And I am wearing Palóc clothing that we were wearing on festive days.”

I am pretty sure that I have identified the photo that Opapa described. He stands between a man and a woman, and all three of them are dressed in traditional Hungarian dress.

The summer was transformational for Opapa. “This month meant a lot to me,” he wrote to Laci. “Nothing interesting has happened ever since.”

While many interesting things did happen to Opapa, the time he spent with the Palóc was formative, and it would reverberate throughout his life. I remember Opapa talking about his summer visits to Hungarian villages decades later, when he was in his 70s and 80s. He loved learning about Hungarian folklore and culture.

Opapa’s summer with the Palóc would also shape his perception of the media. Many of Opapa’s later critiques of “mass” media, I believe, were informed by his experience visiting the Hungarian “folk” and listening to their stories.

***

Nuts to crack:

Am I right about the year/location of the photos in this post? I’m pretty sure of the Palóc photo, less sure about the Scouts.

Also, this was another photo that might be from the same summer. Does anyone remember Opapa talking specifically about any of these photos?

Great post. Of course Opapa told me about his summer in the village, but not much. I didn't even know where it was. But I am pretty sure that is where he got and learned a little of how to play his zither (now on top of our piano and in need of new strings).

George never talked about any of these photos specifically (and we never saw them until after his death . . . ) BUT he really enjoyed talking about his experiences in the country and his study of 'folklore' as it was called then. He also talked about playing the zither (which I think he took up in the country) and he kept his wooden zither all his life, everywhere he moved. It now sits lies atop our piano, strings unstrung and ribbons fading.

For some reason I think George also wrote poetry that summer? We have all his poems in Hungarian, by the way, which he translated for his own book of poetry he published the year before he died. That was such an important summer, I recall, because he said he knew he wanted to study folklore and write poetry.