A few weeks ago, I wrote about how Opapa traveled to Salzburg after the war ended and arrested several Hungarian war criminals, including the former Hungarian Prime Minister, Béla Imrédy. It was a triumphant mission, and one of the proudest moments of his life.

One thing I love about doing this research is that as I dig into Opapa’s life, new pieces of the puzzle emerge — not just through my own research, but also through the generosity, insight, and help of friends and family.

Today, I’m focusing on some new evidence about the Nazis that Opapa arrested that has come to my attention thanks to members of my family. First, I want to share some photos that my sister Emily scanned and sent to me. I’d seen some of them before, but not all. The most exciting (in my opinion) was a photo of Béla Imrédy as he arrived in Budapest after being extradited from Austria.

Imrédy stares straight at the camera as he steps off the plane. Opapa is to the right of Imrédy, looking over his shoulder. On the other side of Opapa is Gábor Péter, the head of secret police in Hungary. Soon after this picture was taken, Imrédy would be tried and convicted of war crimes, and sentenced to death.

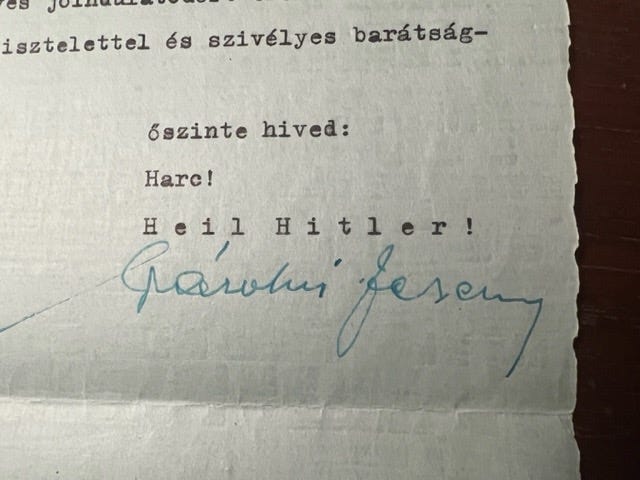

The second new piece of evidence, which my aunt Kathie scanned and emailed to me, is a letter that Opapa took from the desk of a Hungarian Nazi when he arrested them in 1945.

The letter, written in Hungarian, is addressed to Mécser András in Berlin. András Mécser was a far-right Hungarian politician with close ties to the Reich. The sender of the letter is possibly someone named dr gróf Károlyi Ferenc, though I’m not 100% sure, since the signature — which I am having trouble deciphering — does not seem like it matches the name. Still, as you can see from the “Heil Hitler” at the end, this man is definitely a Nazi:

Thanks to Google, I have completed a rough translation of the letter. In it, the author asks András Mécser for help finding work. Due to the “situation on the front lines in Hungary,” he has “moved in with [his] brother-in-law to the Reich to wait for calmer times.” The “situation” undoubtedly refers to the advance of the Russian army, which had begun to encircle Budapest in winter 1944.

The author then makes a request: both his wife and his brother-in-law “want to take up work.” His wife is an “experienced typist.” While neither “speak German perfectly,” he asks Mécser to “find a way for them to be employed in an intellectual position that suits their skills, education and abilities, either at the Embassy or Consulate itself, or at any other institution.”

It’s possible that the author wrote many of these letters as they tried to earn income after fleeing Hungary, and this one was not sent for some reason. Or, alternatively, Mécser was the person that Opapa arrested. (I’m searching for a list of the Hungarian war criminals arrested in Austria, but this will probably have to wait until I can get to the National Archives in DC this summer).

While the letter itself sheds some light on the banal aspects of being a war criminal on the run, I am more interested in the fact that Opapa chose to take and keep this letter: of all the things to grab, why did he choose a letter? Did he think about it as a sovenier? A token of victory? This is one of those times I really wish I could just ask Opapa more about why he kept this letter for the rest of his life. But I’m grateful that he did.