After Opapa arrested Béla Imrédy, the former Prime Minister was interrogated by the US military, and later put on trial in Budapest at the People’s Tribunal (pictured above).

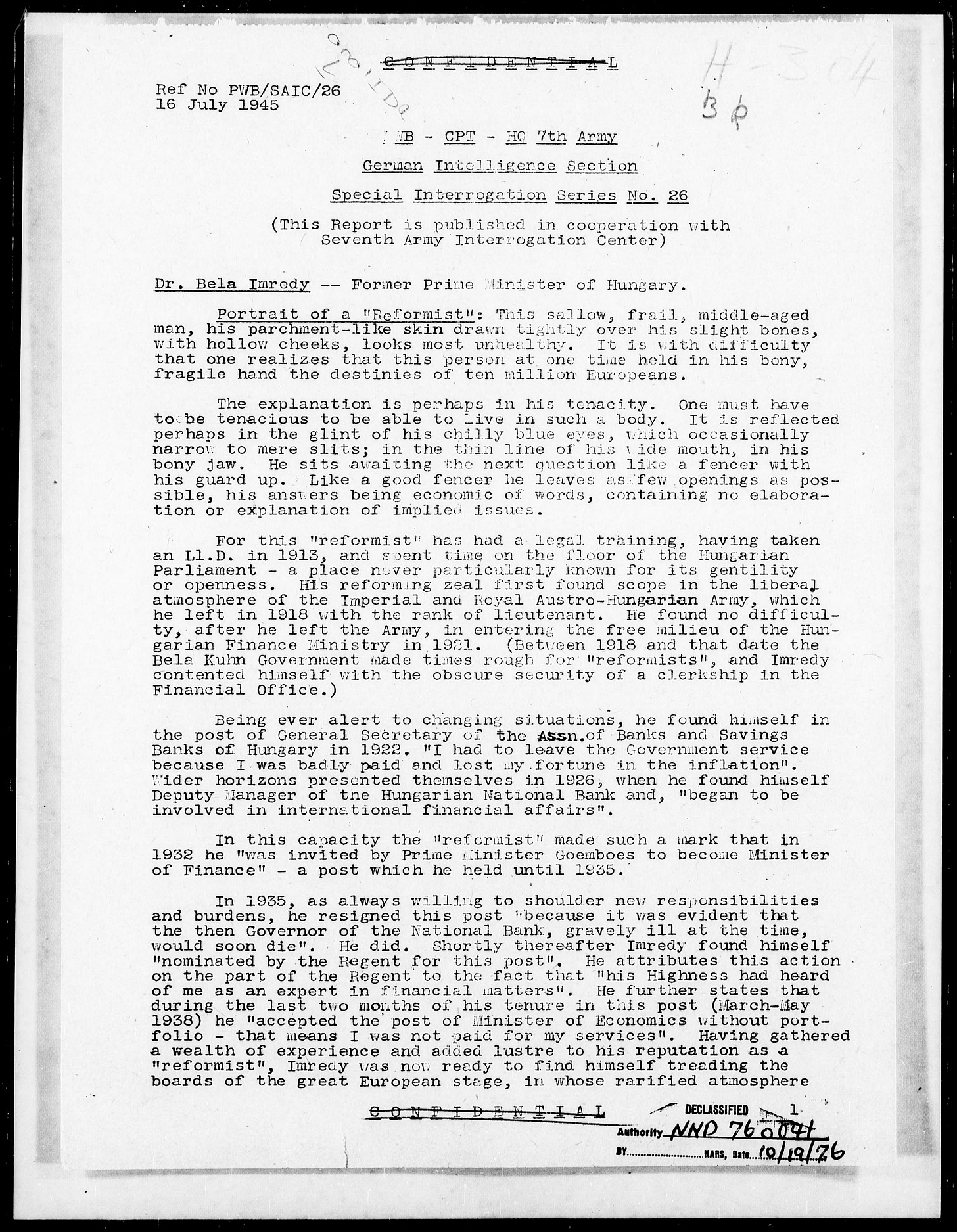

I don’t have a copy of the trial transcript (yet), but I was able to find a copy of the report about Imrédy’s interrogation by the US Army, which was digitized by the National Archives in College Park, MD:

The report was conducted by George Freimarck and Irving M. Rowe of the “Psychological Warfare Branch,” a division of the OSS, and it was declassified in 1976. I *think* it was conducted in Salzburg, before Imrédy was escored back to Budapest by Opapa. It is dated July 16, 1945, so a full four months before Imrédy’s appearance at the People’s Tribunal in Budapest, and a month (I think) after his arrest.

The document is written with a dramatic flair oozing with distain. It begins with a visual description of Imrédy as a “sallow, frail, middle-aged man” with “parchment-like skin drawn over his slight bones,” and “hollow cheeks.” “It is with difficulty,” the authors continue, “that one realizes that this person at one time held in his bony, fragile hand the destinies of ten million Europeans.” Wow.

It is not until later pages that the authors quote Imrédy at length, offering a window into his defense. Here is how he defends the First Anti-Jewish law, which he supported but found to be unsatisfactory:

“With the ‘Anschluss’ of Austria to Germany, Hungary became direct neighbor of Germany and from one day to the other found herself in front of completed changed economic and political conditions. The internal political situation also began to feel immediately the effects of Germany’s direct neighborhood, the extreme right gained more and more ground. The Jewish problem entered in an acute stage.”

Here, Imrédy attempts to blame rising German influence, along with public pressure, for the bringing more attention to the “Jewish problem.” He refers to the Anschluss, or Union, of Germany and Austria as a principal reason for the shifting political calculus. There is some truth to this, though it is also misleading: when Austria became part of Germany in March 1938, it meant that Germany exerted an even more powerful influence on Hungary, and there were numerous factions within Hungarian politics debating how to maintain Hungarian autonomy between Germany and Russia. Still, Imrédy’s statement that “something had to happen to satisfy public pressure” was an unconvincing demonstration of the use of the passive voice to put the blame on an anonymous third party (the “public”) when his own statements at the time confirm his passion for anti-Semitism.

When the interrogation turns to the Second Anti-Jewish law, which Imrédy sponsored, this is how he described and rationalized it:

“It was mainly based on the proportional system, i.e. the fixing of the Jewish participation in different branches of the economic and intellectual professions in percentages. As regards the voting rights my first idea was to form a special electoral body of the Jewish population entitled to send a corresponding number of representatives into the House. But the majority of cabinet members took the view that this would in further consequence lead to a splitting up of the population into national groups. I accepted this view and so the bill contained the abolition of voting rights.” (3)

Again, Imrédy manages to blame others for the bill: he claims that he didn’t want to completely take away Jewish suffrage, but since his idea to “form a special electoral body of the Jewish population” was rejected by the House, he states that he passively “accepted” that “the bill contained the abolition of voting rights.”

Later in the interrogation, when questioned about Jewish deportations to Auschwitz, which began in 1944, he states that he saw, from the window of his motorcar:

“a line of Jews - men, women and children - ten kilometers long being driven from Budapest to Vienna. As I remember, these people were escorted by armed members of Szalasi’s party and the SS.”

Again, blame is directed elsewhere. Here, Imrédy implies that “Szalasi’s party and the SS” are responsible. It’s not untrue: Ferenc Szálasi was an ultra right-wing fascist who was the leader of the Arrow Cross Party and became the leader of Hungary in the last six months of the war. When he gained power, Szálasi supported mass deportations of Hungarian Jews. It was during this period that Arpad Gerbner was taken off a streetcar in Budapest, and never seen again. We still don’t know whether he was transported to Auschwitz, or murdered in a mass execution (probably the latter, since there are no records of his arrival at a concentration camp).

I suppose it’s too much to expect a fascist anti-Semite to demonstrate any kind of remorse or self-awareness, but I still find Imrédy’s defense to be deeply depressing. His refusal to connect his own policies, especially the revocation of Jewish Civil Rights during his leadership, to the escalation of Anti-Jewish policies after he was forced to step down, is either egregious denial or blatant hypocrisy. But of course, this is the same man who - when forced to admit his own Jewish roots - continued to support anti-Semitic policies.

No wonder Opapa described arresting Imrédy as one of the proudest moments in his life.

Really wish we knew more (ie, we had asked Opapa more) about his analysis of this irony. But we did not have your research back then...