Béla Imrédy

Jewish Anti-Semite

Who was Béla Imrédy, the man Opapa arrested in the summer of 1945?

For Opapa, the most important fact was that he was the Hungarian Prime Minister who ushered in the first of the Anti-Jewish laws. Today, I’m going to be looking at what these laws were, and how they affected Opapa and his family. But I’ll also examine some more surprising elements of Imrédy’s life.

The most surprising is the fact that in 1939, Imrédy was forced to step down as Prime Minister because — get this — it turns out he was part Jewish.

But first, let’s start with the legislation that undermined the civil rights of Hungarian Jews.

The first anti-Jewish law was introduced to the Hungarian parliament in April 1938, a month before Imrédy was appointed Prime Minister. According to the text of the law, its’ objective was to create “more effective safeguards of balance in economic life” and to “combat unemployment among the intelligentsia.” What this meant, in reality, was that there would be quotas for Jewish participation in the professions such as law, finance, and academics, in which Jews were considered to be over-represented.1

The first anti-Jewish law passed in May 1938, a few weeks after Imrédy was appointed Prime Minister. Imrédy, however, did not think the anti-Jewish law was satisfactory.

Imrédy sponsored a second piece of anti-Jewish legislation, which became Act IV of 1939. This Act differed from the first Anti-Jewish law in many respects. Significantly, it contained a different definition of what it meant to be “Jewish.” The first anti-Jewish law defined Judaism as a religion, and it recognized the validity of a baptism as long as had been conducted before August 1, 1919. The second anti-Jewish law was modeled on Nazi race theory, and it considered “Jews” to be a race. Baptized Jews, under this legislation, were still Jews.2

The Second Anti-Jewish law expanded on the restrictions of the 1938 law, and it was a disaster for Hungary’s Jews: Jews lost their citizenship rights; they were no longer allowed to sit in Parliament; they were forbidden from working in the Public sector, including education; they could no longer run workshops; and the quotas for Jews in the professional classes were curtailed even further. According to conservative estimates, 40,000 Hungarian Jews had lost their job by June 1939.3

Opapa and his family felt the effects of this legislation quickly: his father, Arpad Gerbner, lost his job. The family was no longer allowed to own a car. And this is when they decided to send their oldest son, George, to the United States to escape the persecution. By June 1939, Arpad wrote a letter to Opapa that acknowledged that they were “sinking.” Unable to work, he had to find a “feudal lord” in order to earn any money.

The new legislation was also a disaster for Béla Imrédy: ironically, the law that he sponsored, which defined Jews by race instead of religion, meant that he had disqualified himself for his job as Prime Minister. In February of 1939 — before the law had even passed — Imrédy’s political opponents publicized genealogical evidence that his great-grandfather was Jewish.

Imrédy faced a choice: what to do with this new evidence that he was, himself, descended from Jews?

He double downed on Anti-Semitism. He urged the Parliament to pass the new anti-Jewish legislation, and admitted that he should not hold political office.

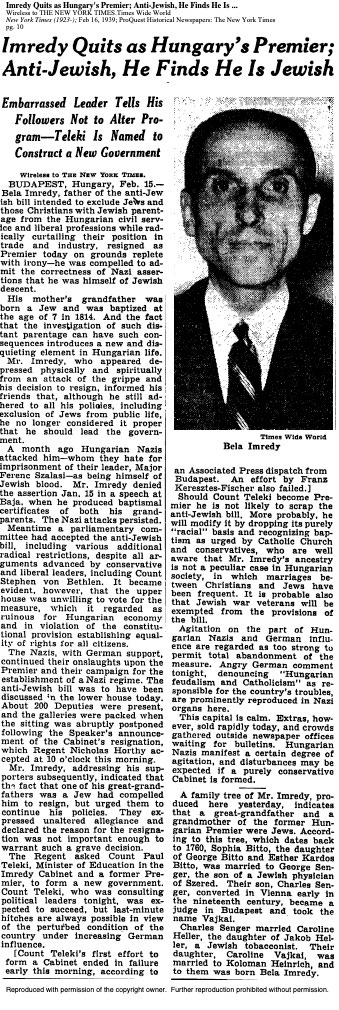

Here is the NY Times reporting about Imrédy stepping down (Dad found this — thanks, Dad!)

According to this reporting, Imrédy announced that “he still adhered to all his policies, including exclusion of Jews from public life,” and thus “no longer considered it proper that he should lead the government.”

The following year, he founded the new pro-fascist, anti-Semitic Party of Hungarian Renewal.

Cited in “The Economic Effect of Antisemitic Discrimination: Hungarian Anti-Jewish Legislation, 1938-1944,” in Jewish Social Studies 48:1 (1986), p. 66

Vagnini, “The Hungarian Anti-Jewish Laws and Relations between Hungary and Germany,” in Complicated Complicity: European Collaboration with Nazi Germany during World War II, p. 70; “The Economic Effect of Antisemitic Discrimination: Hungarian Anti-Jewish Legislation, 1938-1944,” in Jewish Social Studies 48:1 (1986), pp. 66-8. According to Vagnini, some Nazis did not think the Second Law went far enough in its racial definition of Jewish-ness. The third anti-Jewish law, passed in 1941, went this extra step.

“The Economic Effect of Antisemitic Discrimination: Hungarian Anti-Jewish Legislation, 1938-1944,” p. 68