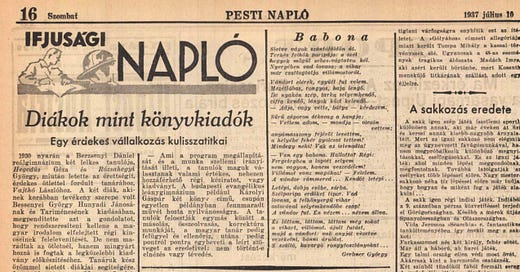

Yesterday, as I was going through the Hungarian newpapers, I found what might be Opapa’s first publication: a poem, printed in Pesti Naplö on July 10, 1937. Opapa was eighteen years old, and had just won the national literary competition.

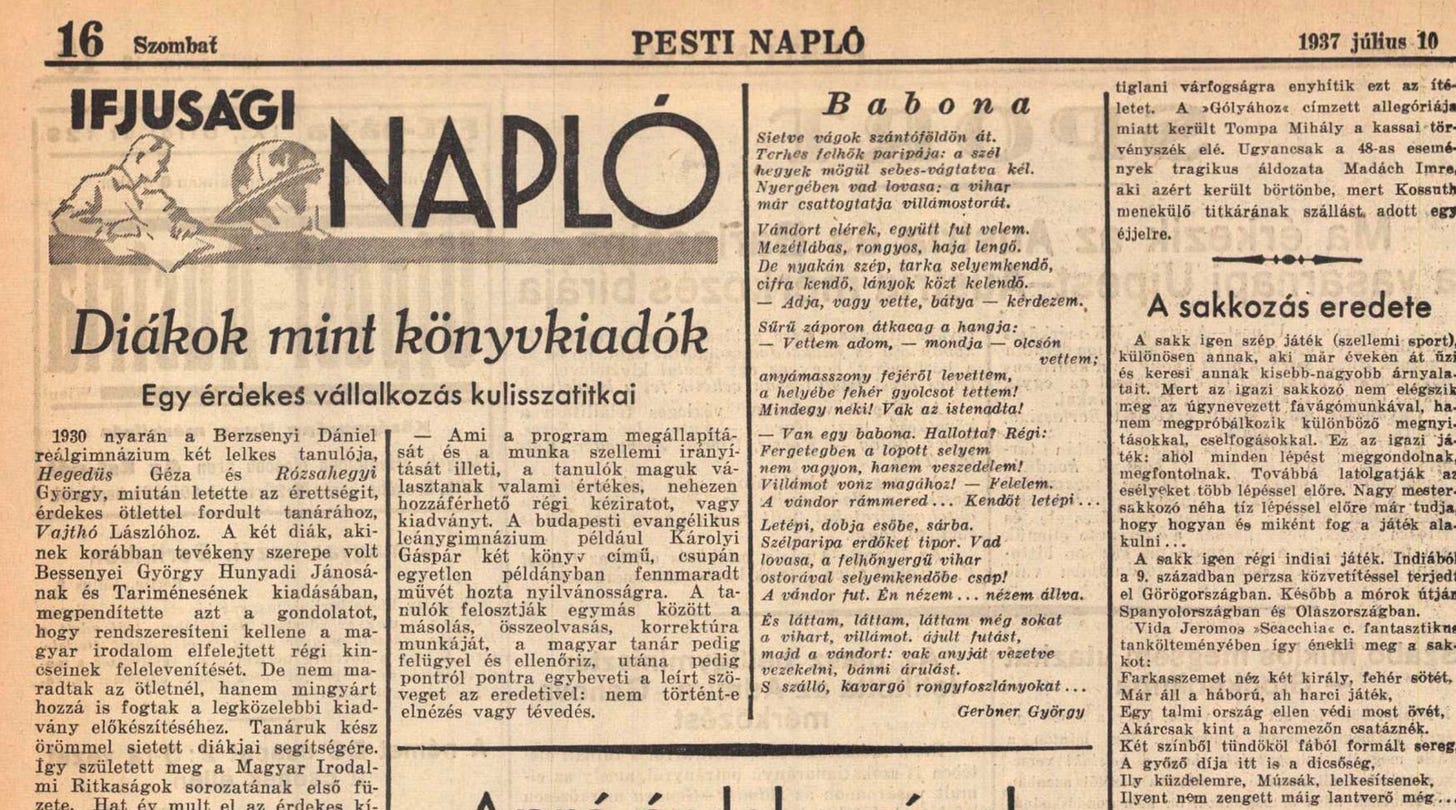

The poem is titled “Babona,” which means “Superstition”:

I haven’t had the poem translated yet, and I don’t want to butcher it with Google translate, so the contents of the poem will remain a mystery for a little while. But seeing it reminded me of how important poetry was to Opapa.

As a teenager, when he was not learning about Hungarian folklore or playing the zither, Opapa was often writing poetry. Poetry, to Opapa, combined beauty, passion, revolutionary fervor, and national pride. As he would later write,

“Writers and poets were admired as celebrities. Their poems were published in the front pages of leading daily papers. They had been the leaders, heroes, and sometime members of patriotic, nationalist movement of liberation from oppression. They became my heroes, models and inspiration. I practiced their style to develop my own, wrote short stories and poetry every night, and eventually, at the age of 19, published a small book entitled “My Poems.” I was convinced that I found destination.”

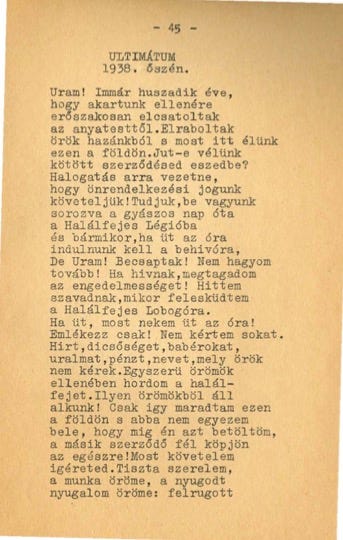

We have Opapa’s book of poetry from his teenage years, and it contains over thirty poems, written between 1936-1939.

Here is one of them, entitled “Ultimátum”:

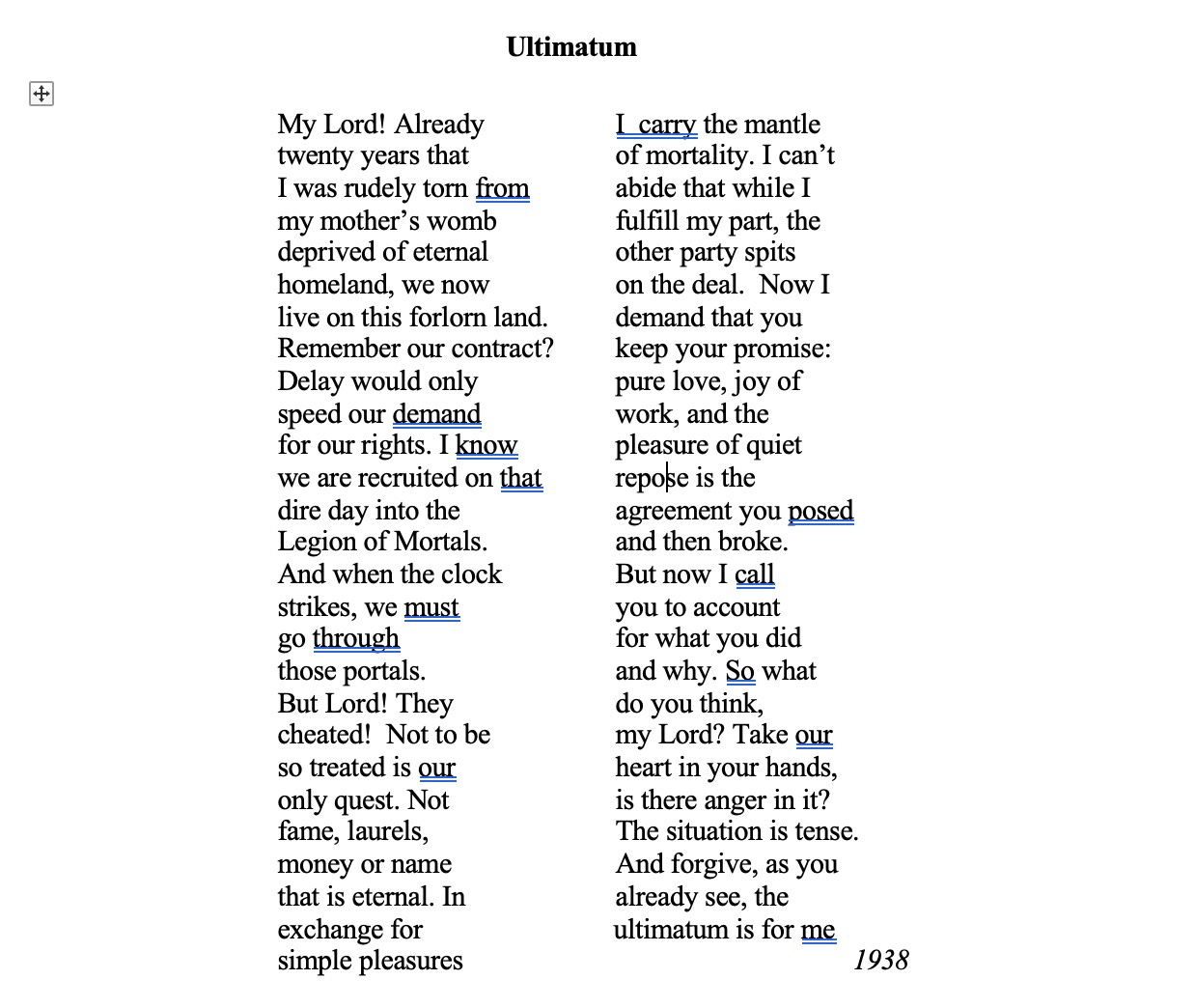

Poetry is notoriously difficult to translate, and Hungarian does not translate easily into English. It is full of puns and double meanings that are impossible to replicate. But fortunately, Opapa translated this one himself. He was planning to use it for his autobiography. Here is his translation:

Opapa wrote “Ultimátum” in the fall of 1938, just a few months before he himself was “rudely torn” from his homeland of Hungary.

When he left Hungary, Opapa also left behind poetry. As he later wrote,

Being uprooted meant isolation from the language, from everyday practice in the language and its dialects, and its subtleties. I have never been able to recapture that in any language. So partly my circumstances and partly my own interests led me to become more a researcher, an analyst, and social critic of cultural production.

To be torn from Hungary, and from the Hungarian language, meant that Opapa could no longer be a poet — his first love. Opapa would soon be fluent in English, but its “subtleties” were not those of Hungarian; it was impossible, he wrote, to “recapture” poetry without his native tongue. Instead, he turned to research, to analysis, to the scientific study of culture.

And yet.

As with so many other things, Opapa returned to poetry in his 80s. In the last years of his life, as he was working on his autobiography and translating his father’s manuscript into English, Opapa started writing poetry again — in English this time. The topics ranged from the whimsical to the political. He wrote about his retirement home, about the petty slights of old age, about his fascinations and his delights. One poem criticized US foreign policy. Others echoed his academic scholarship on consumer culture and mass media. Some mused about what it would have been like to be a different person. A few lamented the way the elderly were treated in society.

Here is one that makes me smile, and reminds me of all of the stacks of paper in Opapa’s office when I was a kid:

My Obsession / One thing I can’t tolerate / is an empty sheet of paper. / When I see it, / I must fill it. / If not now, then later. / I wonder what made me so eager / to write verses if so meager / substance. Never mind! / I can leave all doubts behind / because what you see and read here / for better or worse, another verse / and my obsession, empty paper, / is satisfied—until later.

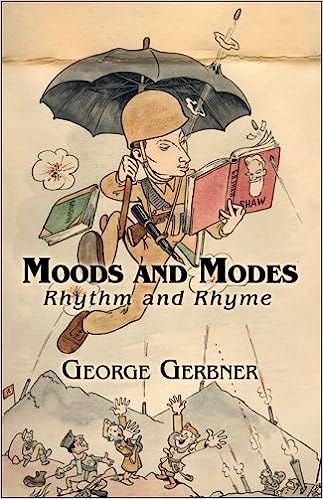

Opapa never finished his autobiography, but he did finish a book of poetry, which was published on December 26, 2005 — two days after he died.

In it, he brought together his teenage poetry with his poetry from his 80s. “Moods and Modes,” he called it. About a quarter of the poems were written in the 1930s. The rest — over 80 poems — were all written in 2005, the last year of Opapa’s life. One them, entitled “A Poem A Day,” captured Opapa’s approach to writing poetry during this time, as well as a bit of gallows humor: “A Poem a Day / keeps boredom away / A poem a week / is still somewhat neat / A poem a month / just for a dunce. / A poem a year / the end is near. / Even more is: / rigor mortis.”

In English, Opapa’s poetry is often humorous and playful. I wish I knew what his poetry was like in Hungarian. It is a divide that seems unbridgeable.

Even as Opapa translated his own poetry, he continued to reflect on this divide between English and Hungarian — and on what he lost when he was forced to leave Hungary in 1939. This is how he introduced his teenage poetry in Moods and Modes, with a verse he wrote in 2005:

I was a poet in Hungary Until uprooted from the country I loved, and whose poetry inspired a revolution that nourished a generation. As the poet Petofy writes: "Rise up Magyar, do not revel. This is the time now or never!" So my poetry, subversive is recreated in English in which I have been naturalized but never homogenized.

Naturalized, but never homogenized.

***

Nuts to crack:

Opapa mentions that he published a book of poetry before he left Hungary. I wonder if this is the book we have (which is typewritten, but it’s not published by a publisher).

Did he publish other poems in Hungarian newspapers?

We have a box of his poetry books in our barn. The cover art (watercolor of GG parachuting while reading) is one of my favorite pieces are art -- but sadly is missing.