The Hungarian newspapers from fall 1945 are a multi-layered trove of information about Opapa. Based on these newspapers, I’ve been able to piece together that Opapa opened an art exhibition at a local high school, and that he went to the theater and cinema regularly - in addition to his work for the US Army. It was also during this time that he met his future wife, Ilona Kutas.

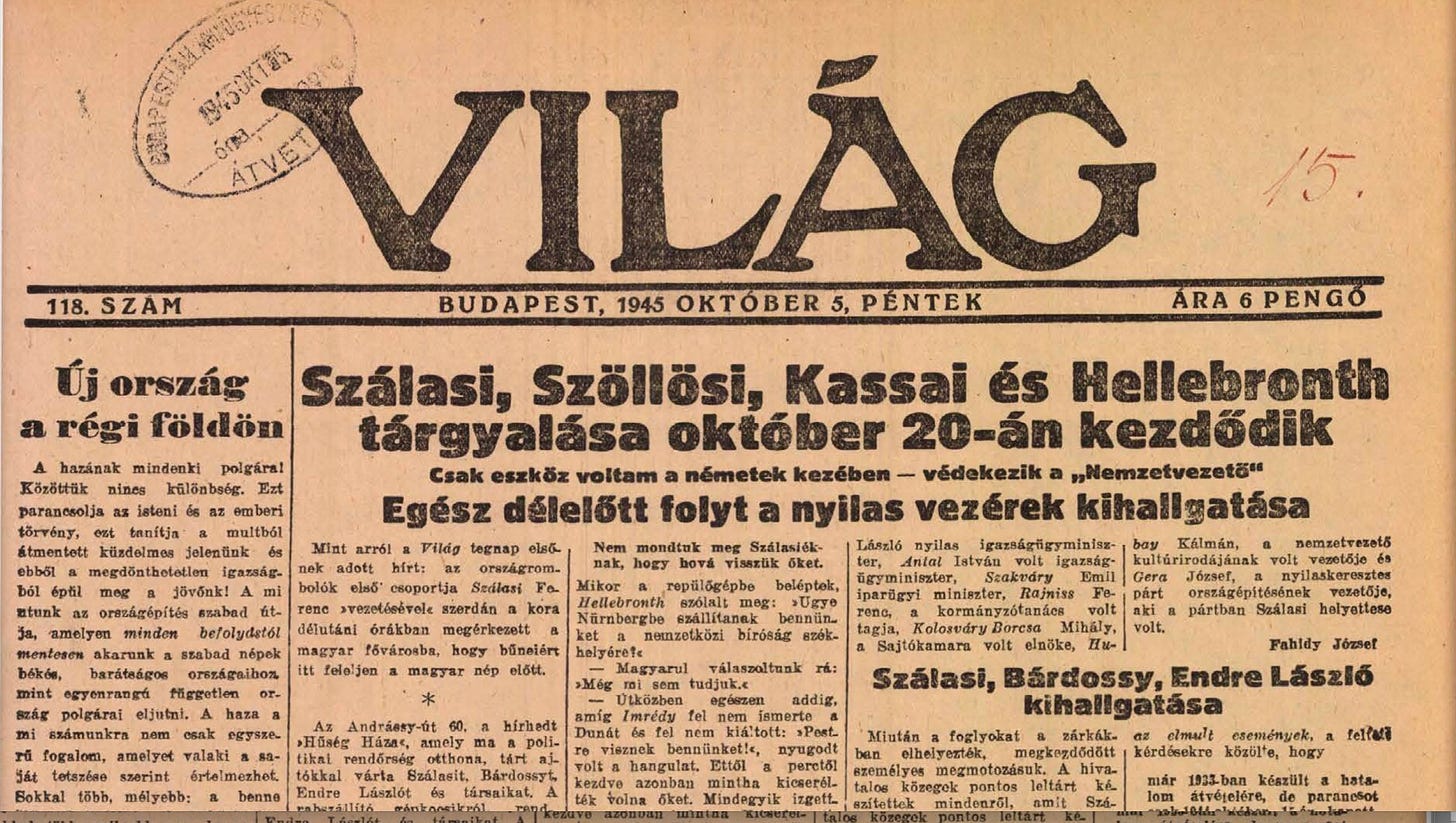

Today, I want to juxtapose two more “finds” from the newspapers that offer different lenses into Opapa’s post-war experiences: the first is a front-page article in Világ about the Hungarian war criminals that Opapa arrested and transported to Budapest. It includes an interview with a 25 year old Hungarian-American and I am 99% sure that the 25-year-old is Opapa.

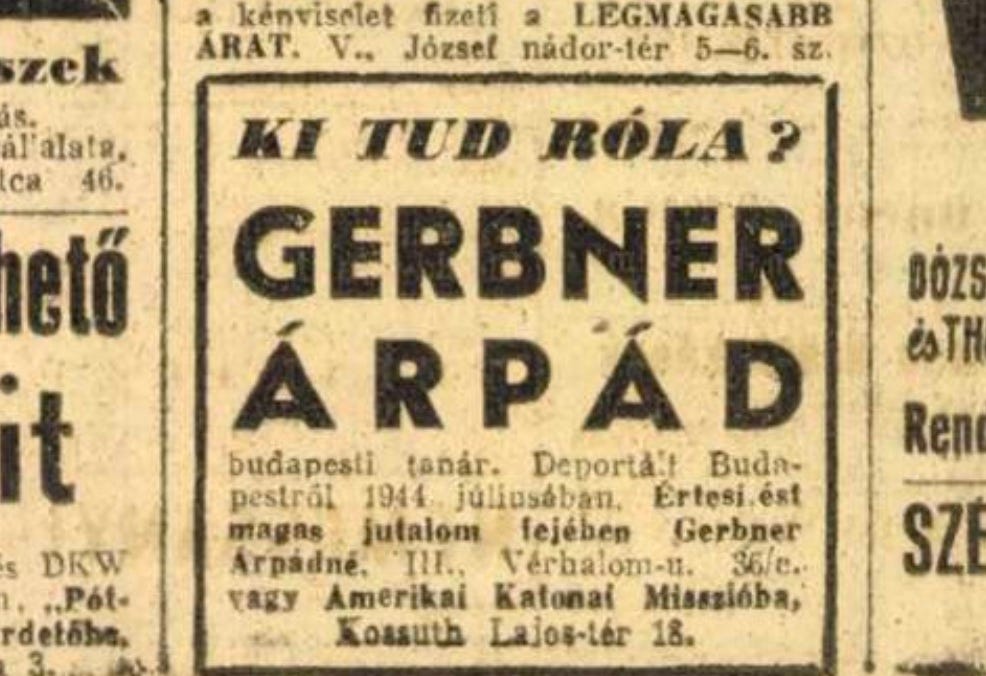

The second “find” is a wanted ad.

In the first article, in the Világ, a triumphant headline asserts that “The trials of Szálasi, Szöllössi, Kassai, and Hellenbronth will be on October 20.” The article, written by Józsed Fahidy, begins with the assertion that the “destroyers of the country,” led by Szálasi, “arrived at the Hungarian capital…to be held responsible for their sins in front of the Hungarian nation.”

After the prisoners are led to their cells, the journalist sits down with a “smiling American soldier of Hungarian origin” who is “about twenty to twenty-five years old.” This is one of the officers responsible for “bringing Szálasi and his team back to Hungary.” Since Opapa’s other Hungarian-American colleague, George Granville, was much older, I am quite sure that this is Opapa.

The journalist asks Opapa about the plane ride with the war criminals: what was it like? What did they say?

I’ve been wondering the same things. What was it like to be in such close quarters with so many people who were responsible for so many atrocities?

Opapa “puts chewing gum into his month and starts talking.” We learn that there were eleven prisoners on the flight altogher. Opapa refers specifically to five of them: former former Prime Ministers Béla Imrédy and László Bárdossy; Arrow Cross leader Ferenc Szálasi; and high-ranking politicians Vilmos Hellebronth and László Endre.

When they took off, the prisoners did not know where they were going. Hellenbroth asked, “You are taking us to Nürnberg, to the seat of the international court, aren’t you?”

The atmosphere on the plane was calm until former Prime Minister Béla Imrédy “recognized the Danube and shouted: ‘They are taking us to Pest!’” Then, the prisoners became agitated, “constantly moving in their seats.” They were “not allowed to talk during the flight,” but Opapa reported that “as we reached Hungary, they secretly said a couple of words to each other.” When they arrived in Budapest, László Endre “grabbed his own hair with his tied hand. He must have tried to find out whether he was awake or he was dreaming.”

Aside from that minor commotion, Opapa reports that “nothing in particular happened during the flight.” The trip took two and a half hours, and with the exception of Bárdossy, the “eleven war criminals are in a good state of health.” They also “brought a lot of luggage.”

In the article, Opapa is described as “smiling” and “chewing gum.” He seems confident and straightforward. Not only has he arrested the war criminals; he has also transported “all the official and private notes” as well as “several historical documents” which will be presented to prove their crimes.

The second newspaper clipping presents a very different story. There is no “smiling” American officer, and no “chewing gum.” This one, which was printed just a few weeks later, is a wanted ad for Árpád Gerbner:

The first sentence is a question: “Ki tud róla?” “Does anyone know?” The rest of the wanted ad reads:

Árpád Gerbner is a teacher from Budapest. Deported from Budapest in July 1944. Information for a high reward to Gerbner Árpádné, III Verhalom street or to the United States Military Mission Kossuth Lajos square 18.

Like the Világ article, this one does not mention Opapa by name. But it offers a great deal of insight into what he was going through. While Opapa was a smiling, gum-chewing soldier in the Világ article, confidently transporting war criminals, this wanted ad is a reminder of the pain and loss that lay under the smiling surface: he had no idea where his father was.

I am quite sure that Opapa was the one that arranged for this ad to be placed in the newspaper. Initially, I thought his mother Margit had done so, but when I saw the date, I realized it was over a year after Árpád’s disappearance, and only a few weeks after Opapa’s arrival in Budapest. If Margit had thought to put an ad in the newspaper, she probably would have done it earlier. Moreover, the “United States Mission” is listed as a place where people can get a reward for information about Árpád Gerbner — another indication that Opapa is the behind the ad.

Opapa continued to take wanted ads out in the newspapers: he ran an identical ad in Magyar Nemzet a few days later, and also had one printed in the Világ on November 6, 1945.

As far as I know, no one ever came forward with information. For the rest of his life, Opapa would wonder what, exactly, had happened to his father.

For me, seeing the wanted ads for Arpad was a jolt: I had been reading about Opapa’s triumphant arrest of the war criminals, his attendance at the theater, the opening of the art exhibit, and the first weeks of his relationship with my grandmother. There was joy, triumph, and love. But of course, this was a time of tremendous mourning as well.

The mystery of his father’s disappearance continued to haunt Opapa. Last week, I was going back through my own email, trying to see if I had any old correspondence with Opapa. I couldn’t find any, but I did find an email from Sister Elvira, who worked as Opapa’s research assistant for many years. The email was dated January 2006, just a few weeks after Opapa died. In the email, Sister sent me information about Opapa’s own research into his past. She wrote:

Right after you left I found the printout of information about that JewishGen network (am not sure this is the right name) that helps Jews search the names of missing relatives. George had a username and password that you can use should you want to pursue the search. You will find the material in an envelope with your name on it.

I had completely forgotten about this email, but it confirms what I knew: that at the very end of his life, Opapa continued to look for his father.

What a stark juxtaposition between his public role as hero and more private role as a son missing his father. Feel like I never really knew the latter part of him. So glad you’re doing this research and writing - really brings him (and Omama and the family) to life in both familiar and new ways.

So sad