Last week, I wrote about my grandfather’s zither, which came from the rural Hungarian village of Rimóc. My grandfather spent the happiest summers of his youth in Rimóc, where he collected Hungarian folktales and learned Palóc songs and customs. He also learned to play the zither. When he returned to high school the following year, he performed Palóc folksongs on the zither for his classmates.

When I was writing my first post about the zither, I wondered when Opapa carried it from Hungary to America: it must have been after the war, I figured. Probably after he met my grandmother. Or maybe it was later, when they returned to Hungary for a visit to family. It couldn’t possibly have been in 1939, when he was traveling alone and broke, without a visa or a ticket, in the hopes of eventually reaching the United States.

I was wrong! The zither was so important to Opapa that he carried it with him — by hand — in 1939, when he fled his homeland.

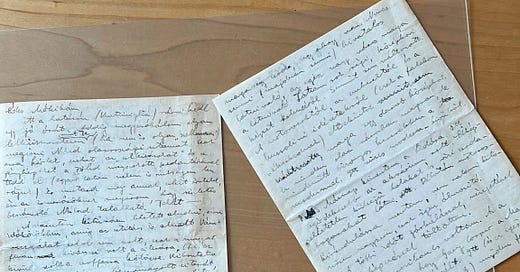

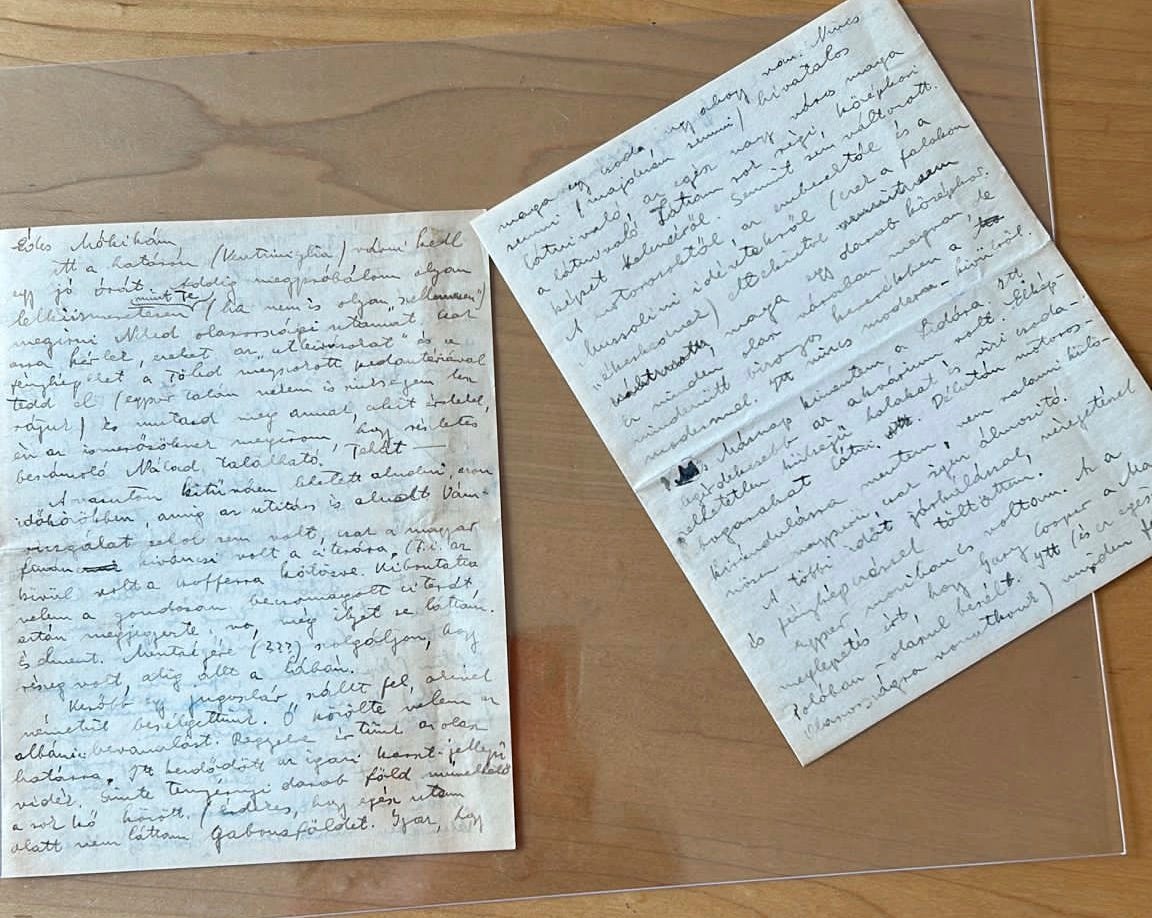

I learned this yesterday, thanks to a “mystery letter” that had no date and no envelope. It turns out that the mystery letter was a draft of a letter that my grandfather was writing to his brother Matyi in April 1939. It is four pages long, but unfinished. Instead of sending it, Opapa kept it, and it remained in a bundle with all of the letters that he received. To date, it’s the only letter written by my grandfather that I’ve seen from 1939. All of the others are written to him.

The letter is sweet and playful, and it offers my grandfather’s story about his departure from Budapest. He begins by explaining that he is “at the border” in Ventimiglia — meaning that he was on the border of Italy and France, en route to Paris, where he hoped to get on an oceanliner headed across the Atlantic. He had to wait “about one hour” and “during that time,” he wrote to his brother, “I will write about my trip in Italy at least so conscientiously as you wrote (even if not in such a “witty” way).”

Opapa’s “detailed narrative” begins with the train ride: “On the train,” he wrote, “it was perfectly possible to sleep,” as long as “our companions were also sleeping.” There was “no customs control anywhere,” he added, “only the Hungarian guy was interested in the zither.”

The zither! I could hardly believe it. The zither is heavy and bulky. As a reminder, here is what it looks like on my parents’ dining room table — it’s over two feet long.

How on earth did he manage to carry it, along with all of his other possessions?

Fortunately, Opapa answered that question in the letter. “As you know,” he wrote to his brother, “it was tied to the suitcase.”

The Hungarian man “made [him] unwrap the carefully packed zither.” Then he said, “well, I have never seen such a thing before.” After that, he left. “He was drunk and could hardly stand straight,” Opapa added.

What an odd and fascinating interaction: it’s not clear whether the Hungarian man was a customs official inspecting luggage, or whether he was just some random drunk Hungarian man, curious about the odd package tied to my grandfather’s suitcase. But either way, I’m glad that the interaction led my grandfather to mention the zither in his letter.

It means that the zither was Opapa’s constant companion in 1939. When he arrived in Venice, after taking the train out of Budapest, he must have carried it across bridges and canals to the Hotel Budapest, where he stayed. The zither then accompanied him across Italy — through Florence, Genoa, and Ventimiglia — and then through France to Paris, where he would have lugged the large instrument to the Hotel Bologne.

When Opapa finally managed to get a ticket on an oceanlinger — the Flandre — the zither boarded the ship with him. Perhaps he played it for fellow passengers, teaching them about the Palóc and introducing them to Hungarian folksongs. The zither then accompanied my grandfather in Mexico, where Opapa spent six months trying to find a way to enter the United States.

Opapa and his zither eventually boarded another boat, to Cuba this time, and then finally to New Orleans, where both zither and Opapa were ordered deported — only to be saved at the last moment. By 1940, the zither found a new home in California, where it likely spent the war years. A few decades later, it would join my grandparents — along with my dad and my uncle Tom — to Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, before finding its’ current resting place in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The more I learn about this object, the more I feel a deep sense of amazement — and gratitude — that it remains in our lives.

***

Nuts to crack:

Are there any other surviving letters written by my grandfather about his experiences in 1939? The letters from his father and brother all reference his letters, but I don’t know whether they still exist.

Did George Gál travel with Opapa in 1939? I know they both left Budapest that year, but I’m not sure if they were traveling together or not. They did not take the same oceanliner (I think George Gale was able to travel directly to the United States), but it’s possible that they spent the early part of the trip together. In this letter, Opapa used the pronoun “we” a few times so I wasn’t sure.

What would Opapa say about the media’s push to have Trump’s upcoming trial in FLA televised?

I love "The Zither, Part 2"!

I do not think that George Gale traveled with Opapa in 1939, I think my Dad would have mentioned that.

Also, I don't think I have seen letters that Opapa wrote to Laslo on 1939, only after the war.