Yesterday, I left off with the German invasion of Hungary, which began on March 19, 1944. At that point, Hungary’s Jewish population had faced years of discrimination and brutality. And yet, Hungary also had the only remaining “intact” Jewish population in Axis-controlled Europe. The country had even become a haven of sorts for Jews from other parts of Europe, who fled to the (very) relative security of the Hungarian state.

After the German occupation of Hungary, however, the Holocaust proceeded with terrifying speed: by July 9, 1944, less than four months after the invasion, German commander Adolf Eichmann and his Hungarian collaborators had deported 437,402 Jews. Nearly all were sent to Auschwitz, where 80% were murdered upon arrival.1

Even this rapid process, however, had phases. Historians consider the Holocaust in Hungary to be the culmination of years of genocidal practice: by 1944, the Nazis had become experts at isolating, deporting, and murdering millions of people. In Hungary, the Nazis followed a blueprint that had been systematically developed in other countries. They were aided by Hungarians who could have impeded the process at multiple points.

As a result, Jews in Hungary were subjected to the rapidly dehumanizing stages of the Holocaust in just four short months. Here is how it happened:

Stigmatization: Within days of the German occupation, the Nazis passed a flurry of new decrees that pushed Jews completely out of Hungarian society. Visual stigmatization was part of it. For the first time in Hungary, Jews were forged to wear the yellow star. Here it is how it was described in the Prime Minister’s decree of March 31, 1944:

“wear a canary-yellow, six-pointed star at least 10 x 10 centimeters in diameter, made of cotton, silk, or velvet, affixed to an easily visible place over the left breast of their outer garments.”2

We know from family stories that Árpad wore the yellow star. He was also subject to another important component of stigmatization: the restriction of movement and information. Jews could no longer go to movies or to restaurants with Christians; they were banned from beaches; their food rations were reduced, and they could shop only 1-2 hours per day. Jews were required to hand over both radios and bicycles, in an effort to restrict access to information and movement. Eichmann also set up a Central Jewish Council, which warned Hungarian Jews to follow the next decrees.3 These were more extreme versions of what Hungarian Jews had been enduring for the previous five years.

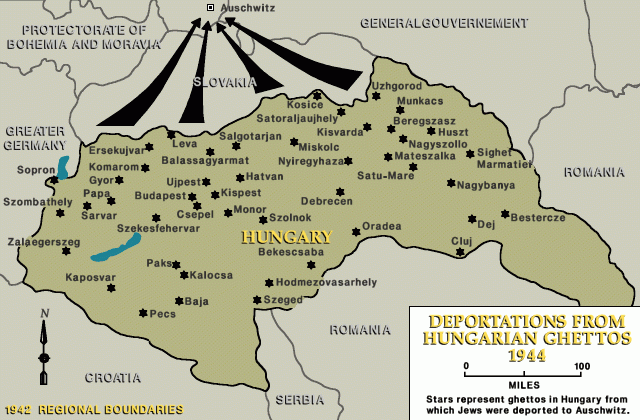

Ghettos: After stigmatization, the German-Hungarian government proceeded quickly with ghettoization. On April 7, 1944, just weeks after the German occupation, Eichmann, László Endre (the newly appointed state secretary), and other officials circulated the first confidential decree about the creation of ghettos. On April 16, just eight days later, authorities began moving Jews in northeastern Hungary. A second, formal ghettoization decree was issued on April 26, clarifying who was to be considered a “Jew,” and making the process public. Over the next ten weeks, Hungarians created 215 ghettos and collection camps throughout the country.4

Munkács ghetto in Hungary. Photo from the Yad Vashem website. In Budapest, by contrast, Jews were placed in “yellow-star houses” and every family was to share one room. In total, 220,000 Jews (and converted Christian Jews) were forced to move into 1,944 apartments that were demarcated as “yellow star houses” beginning on June 21, 1944.

Deportation: Even before the ghettoization process was complete, German and Hungarian authorities had already reached an agreement to deport all Hungarian Jews (aside from those in the Labor Service) to Auschwitz II-Birkenau. They reached this agreement on April 22, 1944, just over a month after the Germans invaded.

In order to carry out the deportations, Hungary was divided into six regions, and operations focused on one region at a time. As a result, the first deportations were in the provinces, and they began in May. The result was one of the fastest executions of genocide in history. As historian Zoltán Vági writes,

Never before had this many people been deported this quickly. Years had not sufficed to fully complete the anti-Jewish “cleansing campaign” in France, the Netherlands, or Poland. In Hungary it took only another fifty-six days (from May 15 to July 9) to deport all the Jews from the country, except for the capital.

By July 1944, however, international pressure — combined with the deteroriating position of the Germans — led Horthy and other Hungarian leaders to end the deportations. On July 9, with FDR threatening military retaliation, Horthy announced that the mass deportations would be halted.

By the beginning of August 1944, then, things had improved slightly for the Jews of Budapest. They had managed to evade mass deportation, and they hoped that the worst was behind them. Most historians write about the months of late July to August 1944 as relatively “calm” and “safe” months, after the terror of the initial months of German occupation from March to July and the Arrow Cross rule that began in October 1944.

And yet, Árpád was murdered on August 15, 1944. What happened?

Obviously, we will never know the full story. But when I posted about finding Árpád’s grave a few weeks ago, Dad responded with a comment that got me thinking. According to Dad, there are actually two different family stories about what happened to Árpád:

I have heard two versions of Arpad's disapearance.. one was the streetcar, the other was that Arpad and Marg[i]t were walking down the street and there was an Arrow Cross checkpoint. Marg[i]t wanted to turn around but Arpad said "no, we will just tell them we're we are going and they will let us through" and they took him away.

Both versions of the story seem eminently plausible. But the second version is especially interesting to me, given what I now know about the phases of the Holocaust in Hungary, and especially in Budapest.

By August 15, many of the Jews in Budapest likely thought that the worst was behind them: unlike the Jews of the countryside, they had not been deported. The Germans were clearly losing the war, and even Horthy had been forced — by mass international pressure — to end the deportations. In the summer of 1944, news about the concentration camps had been widely reported in the international news, and there were public condemnations of the genocide that was taking place in the Nazi territories.

Perhaps, given this context, Árpád was hopeful again. It’s possible to understand taking an extra risk: to get on the streetcar, or to pass that checkpoint. It’s a small gesture, a small effort to reclaim even a shred of normalcy.

But of course, the worst was not over yet.

Árpád was murdered in the relative calm between the storm of the first mass deportations in Hungary, and the horror of late fall and winter 1944, when the Arrow Cross enacted a reign of terror on the Jews.

So if it was the Arrow Cross men at the checkpoint who killed him, his death was a harbinger of what would happen next in the Hungarian Holocaust.

Vági et al, The Holocaust in Hungary, p. xxviii

Prime Minister’s Decree no. 1240/1944, Budapesti Közlöny, March 31, 1944, 3. Cited in Vági et al, The Holocaust in Hungary, p. 73.

Vági et al, The Holocaust in Hungary, pp. 72-4.

Vági et al, The Holocaust in Hungary, pp. 76-82

Interesting to see the research and “official” footnotes alongside quotes from Dad. Really puts a personal family story into a (terrible) moment in history.

Horrifying. At least Opapa was able to bring some of these ....... to justice.