Anti-Semitism was a defining feature of Opapa’s voyage on the S.S. Flandre. But it was not the only story. Today, I’m going to focus on what it was like to be on the S.S. Flandre as it crossed the Atlantic, i.e. before Jewish refugees were denied entry into Cuba and Mexico.

I found a few lines that Opapa wrote about his experience on the ship:

I was traveling first class, with a table companion who was a Loyalist Spanish general fleeing the Franco regime who spoke only Spanish, so our halting table conversation was my first introduction to Spanish that I improved during my stay in Mexico.

George Gerbner, Unfinished Autobiography draft

There are so many interesting pieces of information here. First of all, Opapa was traveling first class. This is because there were no other available tickets, so he either had to come up with money for a first class ticket (he borrowed it) or he had to stay in Europe. So he borrowed money for the ticket, but was still broke. Opapa wrote that this “led to some embarrassments later on,” including that he had to “sneak off the boat without being able to tip the waiters and cabin staff.”

More surprising, at least for me, is that Opapa’s “table companion” was a “Loyalist Spanish general fleeding the Franco regime.” Fascinating!

I knew the Spanish Civil War occurred just before World War II (1936-1939), but somehow, it didn’t really occur to me that the story of Spanish loyalists would overlap so much with Jewish refugees fleeing Nazism in Europe. But the stories are intertwined, and so are the people.

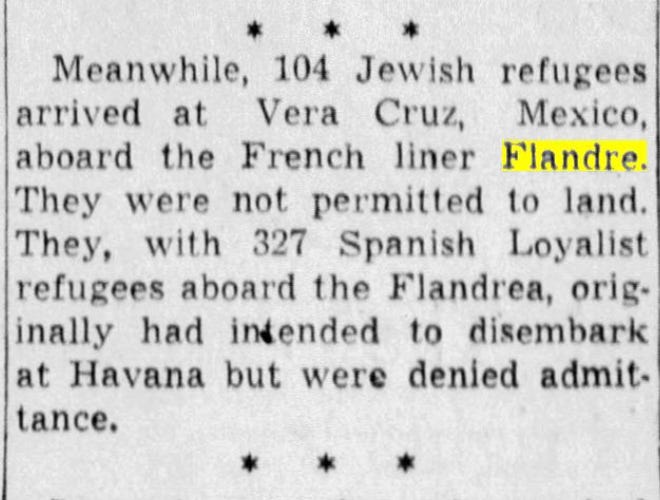

It turns out that most of the passengers on the S.S. Flandre in May 1939 were either Spanish loyalists or Jewish refugees. Here is the clipping from the Minneapolis Star. In addition to the “104 Jewish refugees,” they also mention that there were “327 Spanish Loyalist refugees” aboard the Flandre[s].

I did a little research into Spanish Loyalist refugees, which required a quick refresher on the Spanish Civil War: basically, the Civil War pitted the “Nationalists,” led by Franco — the fascist dictator who ruled Spain until his death in 1975 — against the “Republicans,” who were loyal to the government of the Second Spanish Republic. The Republicans tended to be left leaning, and included republicans, socialists, communists, and separatists, while the Nationalists were a coalition of fascists, monarchists, conservatives, and traditionalists.

After Franco and the Nationalists tried to stage a coup in 1936, both the Nationalists and the Republicans sought foreign aid. France and Britain refused to aid the Republicans (only Russia offered aid), but fascist Italy (under Mussolini) and Nazi Germany (under Hitler) agreed to support Franco and the Nationalists. Their aid helped tip the scales, and on April 1, 1939, Franco and the Nationalists declared victory after they were able to capture Madrid.

It was a horrific and bloody Civil War, and after Franco’s victory, an estimated 500,000 Spanish loyalists (ie those loyal to the now-defeated Republican government) fled the country. Most went to France and, from there, tens of thousands went to Central and South America, including Mexico. Many of those who stayed in France, meanwhile, ended up in Nazi concentration camps after Germany invaded France in 1940.

So the Loyalist Spanish General at Opapa’s table on the S.S. Flandre had just endured three years of a brutal Civil War, and was now forced to flee his country. Like Opapa, he was a refugee, but unlike Opapa, he had already seen horrific acts of violence and murder. And yet, here he was — after all of that — riding First Class on a French oceanliner.

What did Opapa and the Spanish loyalist general talk about? A few things stand out when I think about the possible dinner conversations between this Spanish General and Opapa, a 19-year-old Hungarian Jewish refugee. First, since he was traveling first class, the General was probably relatively wealthy and (formerly?) powerful. Second, he was a general. During the 1936 attempted coup, a large segment of the Spanish military supported Franco, but this man stayed loyal to the Republican government. He must have had interesting political commitments. Third, since the general “spoke only Spanish,” the conversation could not have been too in depth. But it was notable enough that Opapa, writing about the S.S. Flandre sixty years later, still remembered the general and chose to mention him. For me, knowing that Opapa was having dinner conversations with a Loyalist general from the Spanish Civil War offers a surprising and fascinating new dimension to his trip across the Atlantic.

***

Nuts to crack:

I would really like to find a passenger list of the S. S. Flandre. So far, I’ve found the following leads:

The immigration passenger records are available for Vera Cruz, Mexico from 1921-1931 on Ancestry.com, but I can’t find the ones from 1939.

This document probably has a partial list of names from the S. S. Flandre.

This document, a letter written by a passenger on the S. S. Flandre, looks promising, though it wouldn’t offer a full passenger list.

While I haven’t been able to locate the ship list for Opapa’s voyage, I did find a fascinating oral interview with another passenger on the S. S. Flandre. The passenger, Rafael Menda, was 8 years old when he took the Flandre to Cuba, and he was traveling with his parents and siblings. He was also traveling first class, so Opapa probably saw him and his family regularly. The Mendas were Italian Jews, and they spoke Ladino, the Sephardic Jewish linguia franca, which is similar to Spanish. When his family was applying for their visas in France, one of the Cuban officials heard them speaking Ladino, and offered them a different visa than was being offered to the other Jewish refugees. As a result, he and his family were able to disembark in Cuba — unlike the other Jewish refugees. I wonder whether the Cuban official assumed that they were refugees from the Spanish Civil War.

Wow! This is fascinating.

PS, Sharon sings songs in Ladino.

I love it - I keep learning new things about Opapa (and now the Spanish Civil war)