Well, it’s been a whirlwind since I last wrote. We are back in Minnesota, and I’m finally back to writing after several days of unpacking, doctors appointments, and running a workshop for high school teachers (my sabbatical is officially over!).

But what is most on my mind right now is that I just dropped my oldest daughter, Lolo (age 9), off at the airport. She is flying to DC with her grandmother, who will drop her off at Quaker overnight camp for two weeks. It’s the longest I’ve ever been away from any of my children, and while I’m so excited for Lolo, it is still hard to say goodbye — even if it’s just for a short amount of time.

While it’s hardly a comparable situation, the experience made me think about how heartbreaking it must have been for Opapa’s mother, Margit, to say goodbye to her son when he fled Budapest in 1939. He was older — 19 years old rather than 9 — but the situation was terrifying and dangerous: she didn’t know if she would ever see her son again, or whether he would make it to the United States. He had no visa and was only allowed to depart with the equivalent of $5 in his pocket. He was broke and alone.

Over the past couple months, as I’ve translated and read more family letters from 1939, I’ve been trying to understand Margit better. By all accounts, she was a pretty difficult person, very demanding and probably depressed. My grandmother did not have a good relationship with her, and she was not affectionate towards her grandchildren. But one thing is certain: she loved her son, and it was excruciating for her to let him go.

As I’ve pieced together the events of 1939, I have learned that Margit did not want Opapa to leave Hungary: she hated the plan. She was so angry and heartbroken, in fact, that she refused to write to him. I know this only because Árpád mentioned it in his letters to Opapa. In Árpád’s letter from May 21, 1939, six weeks after Opapa’s departure, he offered a partial explanation for Margit’s silence:

Of course, we miss you. And the fact that your mother is not writing to you is partially because she thinks a lot about her work, she can never come home during lunch time, she is tired in the evenings.

Árpád Gerbner to George Gerbner, May 21, 1939

As Árpád indicated, Margit was not only hearbroken and angry that Opapa left, but she was also extremely tired and busy. She worked as a dressmaker and a photographer, and she had recently been forced to give up their car (due to anti-Jewish legislation), meaning that she had to take public transportation and was no longer able to come home for lunch.

Three months later, in July, Margit had still not written to Opapa. This time, Árpád was more direct in his letter:

My dear György, if you can make your mother write to you with your remark that “her silence does not mean any good” – then you will surely learn from her what it means…I warn you that her silence might also mean that your departure was against her permission, and its consequences are still not to her liking. I hope that these waves will calm down.

Árpád Gerbner to George Gerbner, July 12, 1939

From this letter, we can surmise that Opapa was frustrated — and probably hurt — that his mother refused to write. In a letter to his father, he wrote about “her silence.” It response, Árpád alludes to the real reason that she was not writing: Opapa left “against her permission,” and she was still angry.

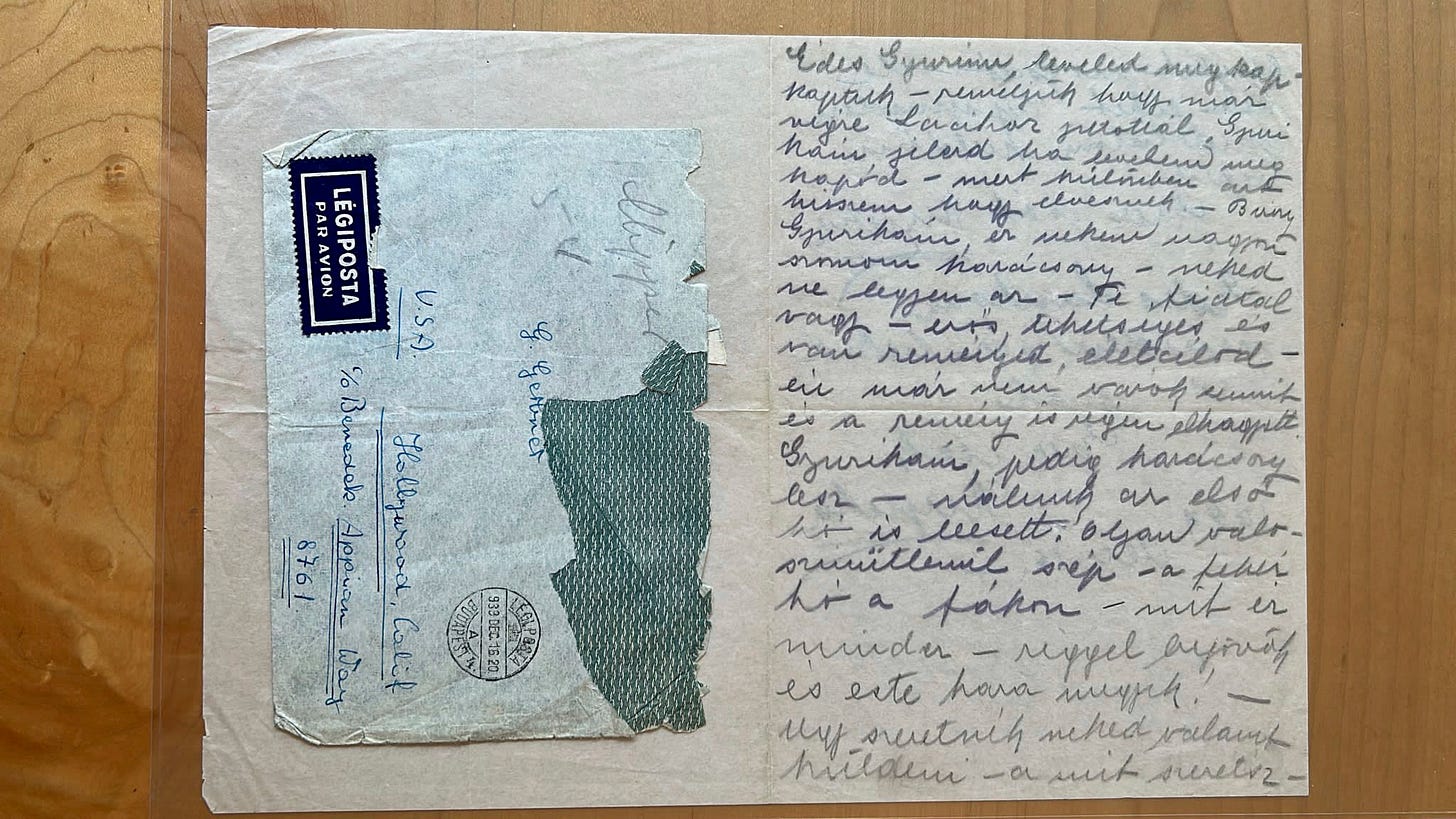

It took nine months — until December 1939 — for Margit to write to her son. Her letter does not mention her long silence, but it is full of sadness:

My dear Gyuri, I – we – have received your letter. We hope that you could finally get to Laci...My little Gyuri, this is a very sad Christmas for me – you should not have [a sad Christmas] – You are young, strong, talented and you have hope, goals in your life – I am not looking forward to anything anymore and hope has left me long ago.

Margit Gerbner to George Gerbner, December 16, 1939

Margit seems truly depressed. “You are young, strong, talented and you have hope, goals in your life,” she writes to her son. But “I am not looking forward to anything anymore and hope has left me long ago.”

Margit still saw some beauty in the world: “It is so unbelievably beautiful, seeing the white snow on the trees,” she wrote. But then she went back into a place of nihilism: “what does any of this matter – I leave [for work] in the mornings and I go home in the evenings.”

Despite her ennui, Margit wanted to make her son happy: “I wish I could send you something – something that you like, bejgli, with walnut, but it is not possible!” Instead, she sent “a thousand kisses.”

I love the reference to bejgli — Hungarian pastries rolled with walnut or poppy seeds.

Margit’s next letter, addressed to both Opapa and Laci, her oldest son, was even more despondent, though she was relieved to know that Opapa had finally made it to California, and reunited with Laci:

My dear Laci, Gyuri, I am waiting for your letters every single day – though now I am not so troubled that I know – that you, my Gyuri, are with Laci. I am with you all the time, every day and I can image how surprised Laci was when he saw you, Gyuri. I cannot write anything good about myself. My health could use a lot of improvement. The weekdays go by somehow – but the holidays – are unfortunately really bad. I spent New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day in bed – I was sick, with very heavy pain in my heart and nerves. Nothing helps, even if I conquer myself unconsciously – a lot of things hurt. When will we see each other?

Margit Gerbner to Laslo Benedek and George Gerbner, January 7, 1940

Margit may have been depressed even before her son’s departure, but the pressures of the previous year had clearly taken a toll: from Árpád’s letters, I know she had lost one of her employees, and they were forced to give up their car. So Margit was now working from dawn to dusk, without a break, trying to make ends meet. Her husband would soon lose his job due to the anti-Jewish legislation, putting even more pressure on her.

There were good reasons to be depressed. And there were good reasons to be heartbroken. Reading Margit’s letters, I shudder to think of what would come next for her — her younger son would go to a labor camp, her husband would disappear. She would have no idea whether her older sons, both in the United States, had survived.

“When will we see each other again?” Margit wrote in January of 1940.

It would take nearly six more years, but she would see her son again. After the war, when my grandfather returned to Budapest, he reunited with his mother. Opapa wrote about the experience in his semi-fictionalized short story, “Inherit the Earth.” While it’s impossible to know how much of this recounts the real sequence of events, I think it offers a compelling picture of a mother’s tearful delight to see her son after so many years, and so much misery:

[H]e came to the house. It was standing. A few bulletholes here and there, but still standing….The neighbors looked out the window when he stopped the jeep in front of the house. There were shouts and excited whispers, and a woman came around the corner walking slowly toward the house, looking at the pavement, when one of the neighbors yelled “Hurry. Don't you see? Your son is here. Your son, your son. He's come back.”

The woman lifted her head, and raised her arms so that the packages of groceries she was holding fell on the street and scattered but she didn't notice. She ran and fell into his arms…

"I'm back, mother, I'm here, Now this is no time to... Let's go inside, mother."

"Let me touch you again, just let me touch you... You look so beautiful. If I had known... We have hardly any food in the house. Where are my groceries... It's you, you didn't change."

"I brought all the food you need, mother. And clothing. And coffee, soap, everything. You don't have to worry about that any more."

"Look… in the garden. I have kept them growing, see how they grew? Remember when you planted those trees? Oh, the furniture was all broken. This room here was a stable. They broke that wall there. But I cleaned up everything, and I wanted to have window‑panes too by the time you came home."

"We'll get the windows, mother. We'll get furniture too. You don't have to worry."

"Oh,…I'm trying not to cry ...so hard...but you didn't change, you smile just like when you were a little boy.”

George Gerbner, “The Meek” (1946)

***

Nuts to crack:

Margit mentions celebrating Christmas in her letters to Opapa. I’ve been trying to figure out the meaning of this — how common was it for assimilated Jews to celebrate Christmas in 1930s Budapest? Had Margit been baptized?

I’m trying to figure out more about Margit’s work: one of Opapa’s friends, Péti Gál, write that he sold fashion designs to Margit. What type of designs, I wonder, and who was her clientele?