After a busy summer arresting war criminals and going on secret missions, Opapa returned to Budapest in late August or September 1945. He had recently learned that his father had disappeared, but his mother was still alive - and desperate for him to come visit.

Instead of trying to imagine what it must have been like to return to his war-torn hometown, today I want to share a short story that Opapa wrote soon after the war. The story has autobiographical elements, although the protaganist is named “John,” rather than “George.” It recounts “John’s” departure from Hungary in 1939, and his return several years later — after the war, and after disappearance of his father.

I’ve read this short story before — years ago. It brought me to tears then, and it brings me to tears now. Opapa completed the story upon his return to the United States, in December 1946.

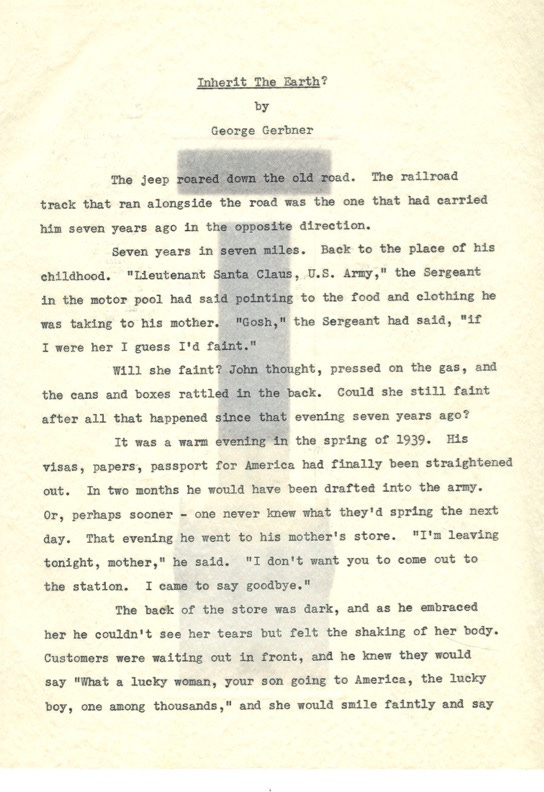

Here is a copy of the first page of the original typewritten transcript:

Here is the full transcript, exactly as Opapa had it on his computer when he died in 2005:

Inherit The Earth

by George Gerbner

8322 Livingston Way

Hollywood 46, CA

(1946)

The jeep roared down the old road. The railroad track that ran alongside the road was the one that had carried him seven years ago in the opposite direction.

Seven years in seven miles. Back to the place of his childhood. "Lieutenant Santa Claus, U.S. Army," the Sergeant in the motor pool had said pointing to the food and clothing he was taking to his mother. "Gosh," the Sergeant had said, "if I were her I guess l’d faint."

Will she faint? John thought, pressed on the gas, and the cans and boxes rattled in the back. Could she still faint after all that happened since that evening seven years ago?

It was a warm evening in the spring of 1939. His visas, papers, passport for America had finally been straightened out. In two months he would have been drafted into the army. Or, perhaps sooner -- one never knew what they'd spring the next day. That evening he went to his mother's store. "I'm leaving tonight, mother," he said. "I don't want you to come out to the station. I came to say goodbye."

The back of the store was dark, and as he embraced her he couldn't see her tears but felt the shaking of her body. Customers were waiting out in front, and he knew they would say "What a lucky woman, your son going to America, the lucky boy, one among thousands," and she would smile faintly and say, "Yes, it is a great fortune, a great luck," and would have to lean on the counter not to collapse.

His father helped him carry his bags to the train. He had bought a ticket to the suburbs so he could be with his son a few minutes longer. The train pulled out slowly, and his father took off his rimless glasses, wiped them carefully with a piece of antilope skin he always carried with him for that purpose, and John noticed in the misty light of the tourist coach how pale and flabby his cheeks had become, how gray and sparse his hair, how the corners of his mouth curled downward, how his eyes were moist and inward-looking, searching, searching, for something to say.

His father had been a teacher and a writer of books on history and culture, books that were never published. He had one subject, for example, a group of essays, or perhaps a book, which people abroad might appreciate, might even consider prophetic. He had been working on that the last few months before John's departure, and had told him about it. It could be entitled "The Fall of Rome." It would show that Rome fell because too few had thought it really worthwhile to work and fight for it at a time when the real morality was the one that had spread from the Syrian lands.

"Why battle, why die they thought," he had said, "if it may be true that the meek shall inherit the earth? Ecco. The subject might be timely indeed."

The train had been slowing down and they still hadn't said a word.

"John," his father said then, abruptly, as if realizing that he had been wasting precious minutes when he should have been giving some fatherly advice, "it just occurred to me that you should be careful with eating ice cream. Remember all those cases of ice cream poisoning last summer? It seems they mix it with something to give it color. Vanilla, they say, is especially dangerous."

The train had come to a stop in the suburbs. "John," his father said, "take care of yourself."

They embraced. His father stroked John's hair once or twice and pressed it to his shoulder and held it there for a second. Then he was gone.

All that was seven years ago, same road, opposite direction. John kept jumping back over the distance of a few yards (and seven years) to that old‑fashioned tourist coach with the gaslight burning over the door, his father sitting on the opposite bench, the train slowing down, time melting into minutes that will never come back, he sitting there knowing all he knew now, all he should have said then, and there was so much, so terribly much to say.

"Dad, listen to me," he should have said. "Please, please do as I say. Sell the house. Sell your things. Make mother sell the store as long as she can still do it. Take up another name. Get false identification papers. Go to the country. No...first look up some people, talk to them. It will be hard to find them but you must find them. They can help you. They call themselves the resistance, the underground. They will tell you what to do, how to fight and survive at the same time. Please, Father, listen to me! That is our only chance. Otherwise we shall not see each other again.”

John could almost see his father’s incredulous look and raised eyebrows.

"Son, you are delirious," he would have said. "What got into you? I an a teacher. Your mother and I are known and respected people. We have friends of some influence, we have a home, we have our work... Why in the world should we hide? And how could we fight? and Why? Isn't there enough hysteria stirred up already?"

"But, father, you don't understand. You don't know what will happen! Please, believe me', You don't know what beasts your respectable people will turn out to be. They are building up a monster that will get out of hand. And they won't help. Your name and loyalty won't help. Your influential friends will turn their faces when they'll see you on the street; they will go home and pull down the shutters and close their eyes because even under the shutters they will see many people being dragged through the rainy streets... And you will be there, marching, yes you will be there in a light summer suit just as the gendarmes picked you up on the streets on a warm June afternoon, and there will be no position and no name, and no respect, nothing, nothing! You must help yourself, father, you must do things you've never dreamed of doing before, you must fight to survive, fight before it's too late!"

That is what he would have said if he had only known then what he knew now. But now it was too late. Seven years too late. Twenty million lives too late. One of them his father, just as the gendarmes picked him up in a light summer suit, walking on the street with his wife, on that warm June afternoon. In a letter she told him how it happened.

They ran into a roadblock. Gendarmes half a block ahead had closed off the street and were stopping everyone. She pulled on his arm and begged him, in a whisper, to turn back. But he whispered back that that was silly. It would only make them suspicious." On the contrary, be said, he will walk up to the gendarmes and ask them what the commotion was all about. Or ask them directions to a certain street—isn't that, after all, what they were supposed to give?

He couldn't finish his question about a certain street. The gendarme looked at the yellow star pinned on his coat and grabbed him by the collar. He turned with pained surprise but smiled and said to her: "Don't worry, I'll be right back." A streetcar stopped on the corner, and the gendarme pushed him up on it and got up after him. He was still looking at her with a frozen smile, his eyes pleading: "Don't do anything... remember who we are.. . this must be a mistake ...I'll be back."

Then she couldn't see him any more. She felt the stare of the other gendarmes looking her over - blond hair, blue eyes, face white as chalk and heard one of them saying: "Don't you know it's against the law to walk with a Jew?"

A streetcar came the other way and stopped jerkily but nobody got off. Suddenly she said "It's late. I must fix dinner for him," and went on, hurriedly.

John drove almost automatically through familiar streets. The playground where he had spent his afternoons... The tennis courts where he also went ice-skating in the winter... The church and all the pigeons... The hill he used to climb and where he was once frightened by a man who pounced on him saying "Want money? Want money?' and tried to drag him off somewhere... the school he used to go to and, yes, the ruins all around with grass growing on the jagged walls like seaweeds over a submerged city.

Then he came to the house. It was standing. A few bulletholes here and there, but still standing. On the door there was a big, handwritten sign saying "Please wait. Will be back immediately." Weather-beaten sign, must have been out in rain, snow, sunshine; the sign of a woman, a wife and mother who is alone with nothing but a faint hope that one day, sometime, someone will come back...

The neighbors looked out the window when he stopped the jeep in front of the house. There were shouts and excited whispers, and a woman came around the corner walking slowly toward the house, looking at the pavement, when one of the neighbors yelled "Hurry. Don't you see? Your son is here. Your son, your son. He's come back."

The woman lifted her head, and raised her arms so that the packages of groceries she was holding fell on the street and scattered but she didn't notice. She ran and fell into his arms.

"Johnny, Johnny, Johnny, Johnny.”

"I'm back, mother, I'm here, Now this is no time to... Let's go inside, mother."

"Let me touch you again, just let me touch you... Johnny, Johnny. You look so beautiful. If I had known... We have hardly any food in the house. Where are my groceries... Johnny, it's you. It's you, you didn't change."

"I brought all the food you need, mother. And clothing. And coffee, soap, everything. You don't have to worry about that any more."

"Look, Johnny, look in the garden. I have kept them growing, see how they grew? Remember when you planted those trees? Oh, the furniture was all broken. This room here was a stable. They broke that wall there. But I cleaned up everything, and I wanted to have window‑panes too by the time you came home."

"We'll get the windows, mother. We'll get furniture too. You don't have to worry."

"Oh, Johnny, I'm trying not to cry ...so hard...but you didn't change, you smile just like when you were a little boy...here, I saved these, I kept them under my bed every night. He said they're important, he always said they must get to America, they must get to our son Johnny, your father said. Here, I kept them for you."

John took the thick bunch of papers. They were yellow around the edges, tied with a ribbon. Typewritten pages with penned insertions and marks in his father's methodical handwriting. A collection of essays, or, perhaps a book. Why Rome really fell. Timely subject indeed. He knew he would never open and read those papers. Those last fifteen minutes with his father on the train, without a fighting word, without a cry, without even a tear, he thought. For why struggle, why fight the tyranny of Rome? Why yell or shout or cry, or demonstrate on the streets, or give up a business, a pulpit, a three-room flat, a radio-phonograph combination, a cupboard full of China -- and why go to the mountains? It is so much more civilized, so much more moral and respectable to be law-abiding and to listen to the best authorities and to consider both sides of a story, and to be careful with eating ice cream, and to quietly write a book, and to gently, peacefully go to the slaughter like cattle. The meek shall inherit the earth?

"What did you say, Johnny? What did you say?"

"Nothing, mother. American slang. Like hell, I said. Like hell."

Made me cry.

I wonder what details he changed besides his name and the subject of his father's book. Now I do think I realize where the two version's of his father's arrest are in my head. This version is obviously from the story. The version of him being dragged off the tram car is what Opapa told me, so I would guess that is what happened (assuming that Margit told Opapa what actually happened).

Also made me cry. And reading the story after all your previous posts, it’s like reading it as a different person—like watching a movie, where you just know what’s happening and want to do and say something but can’t. Like you’re in a third realm. Such beautiful writing (yours and Opapa’s).