Ok, here’s something wild. Some of you may remember the post about my grandfather’s short story, “Inherit the Earth,” which he wrote in 1946. It is a semi-fictionalized version of Opapa’s departure from Budapest in 1939, and his return in 1945 — after his father had disappeared.

In the short story, the protaganist is named “John,” not George, and I’ve been trying to figure out how much of it is autobiographical, and how much is fictional.

In a previous post, I wrote about how in the short story, the father has been working on an academic text on the “Fall of Rome.” The climactic moment of the story comes when John returns from the war, and all that is left of his father is his yellowed manuscript. In the short story, “John” says he will never read the manuscript.

Árpád, like the father in the story, also left behind a manuscript, but it was about the History of Human Culture, from prehistory to the present. Since Árpád’s manuscript was not about the Fall of Rome, I assumed the references to Rome in Opapa’s short story were fictionalized.

But it turns out, I was wrong.

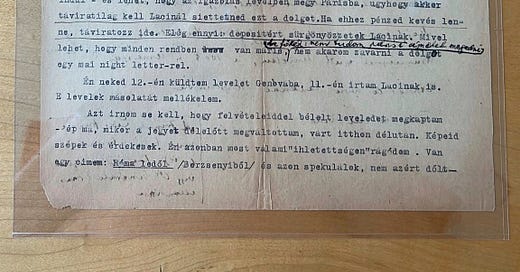

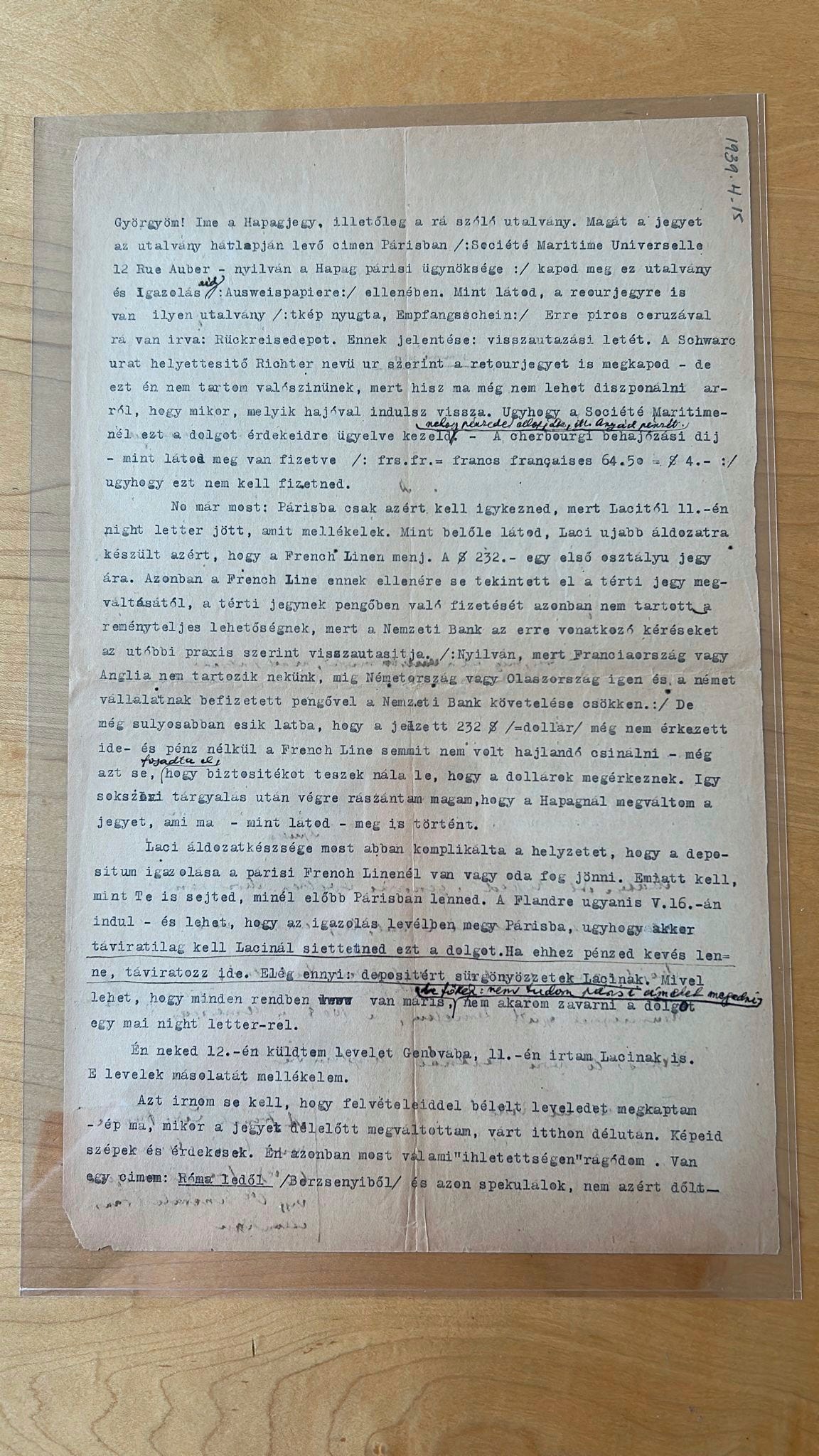

Opapa was actually quoting Árpád directly in the short story. He was quoting from a letter that Árpád wrote to him in 1939, when he was traveling to Paris, hoping to get on a ocean liner headed for the Americas.

I had the letter translated last week. After a few paragraphs related to logistics, Árpád writes about his “inspiration,” a line from the Hungarian poet Dániel Berzsenyi about “Rome falling.” He then offers his own theory about why Rome fell:

Rome has fallen because nobody considered it worthy to work, to fight for it – when the real morals were the ones spreading from the land of the Syrians towards Europe.

And here is Opapa’s line, from his short story, describing the manuscript the father is working on:

It would show that Rome fell because too few had thought it really worthwhile to work and fight for it at a time when the real morality was the one that had spread from the Syrian lands.

It’s an almost word-for-word translation of the letter, with a few slight adjustments, mostly due to translation.

I found this connection to be stunning. Among other things, it made me realize that Opapa must have been reading, and re-reading, the last letters he had from his father while he wrote his short story. It makes sense, of course, and it is deeply touching.

Knowing this adds a new dimension for me regarding Opapa’s relationship with his father’s letters — the letters I am now reading myself for the first time. Reading his father’s letters, and writing about them, was part of his mourning process. They were the way he remembered his father, the prism through which he processed his father’s disappearance.

I can also see what Opapa chose to quote, and what he did not. In the full letter, Árpád actually continued his explanation of why Rome fell:

So: Rome made two major mistakes. One of them was destroying Carthage and making Carthaginians go all over the world – and the other was destroying Jerusalem and sending the spirit of Jerusalem all over the world, moreover, taking it into the Empire. Ecco! – Of course, the topic is relevant today. The “law” will be made in a couple of days – and the economy is struggling already … I hope, that until you will be at sea – at least – everything will be calm…

For Árpád, the Fall of Rome was both a historical event, and a metaphor for current politics. It was how he made sense of foreign policy and law. But Árpád does not follow the same trajectory as the “father” in Opapa’s short story. He writes a paragraph about the Fall of Rome, and then he returns to logistics: he is working on a book, but it’s about human history, and Rome is barely mentioned.

Reading the letter next to Opapa’s short story makes me want to think more about Árpád’s perspective. In the letter, Árpád wrote that his inspiration was the Hungarian poet Dániel Berzsenyi. So I looked up Berzsenyi’s poem that Árpád was reading. It’s called A magyarokhoz, “To the Hungarians” and it was written around 1800, so over a century before Árpád was writing.

In the poem, Hungary is declining — like Rome, Troy, and Carthage. The poem actually features Árpád, who was the celebrated head of the Magyar tribes in the 9th/10th century. In the poem, Berzsenyi excoriates the Hungarians for their way they have treated each other:

Oh you, once mighty Hungary, gone to seed,

can you not see the blood of Árpád go foul,

can you not see the mighty lashes

heaven has slapped on your dreary country?

Amidst the storms of eight hundred centuries

a thousand times, in anger,

you trod upon your own self, your own kin.

Your beastly morals scatter it all to dust

a brood of vipers, venomous, hideous,

lay waste the castle which beheld the

hundreds of sieges it used to smile at.

I can see how, in 1939, this poem might have helped Árpád make sense of the world crumbling around him.

***

Nuts to crack:

What “law” was Árpád referring to in his letter? The letter was written April 15, 1939.

I’m curious how others interpret his reference to the “spirit of Jerusalem.” Is he talking about Christianity? Or Judaism?

Not really a “nut” to crack, but here is the full Berzsenyi poem translated into English.

This is a phenomenal find, Katie - well done. George, unlike “John”, read his father’s work. It is fascinating to see see Arpad’s intellectual trail being followed by George, and now you - very poignant.

The literary connections here are indeed stunning. Amazing. Your use of literature in your research gives so much depth to the stories -- Arpad and George were both very literary -- just like you. xoxo