Lovse Ivan

A window into Partisan Slovenia

Today, I’ve been reading through letters that Opapa wrote to his half-brother, Laci, in 1946. They are fascinating, thoughtful letters, describing post-war life in Budapest and Vienna. They also include my grandfather’s first descriptions of my grandmother, whom he met soon after the war (a story for a different post!)

One letter, however, goes back in time: to Opapa’s experiences in Slovenia during the war. I have already written a few posts about this: how Opapa parachuted behind enemy lines, how he joined up with the Slovene Partisans, and how he spent the last three months of the war fighting alongside them.

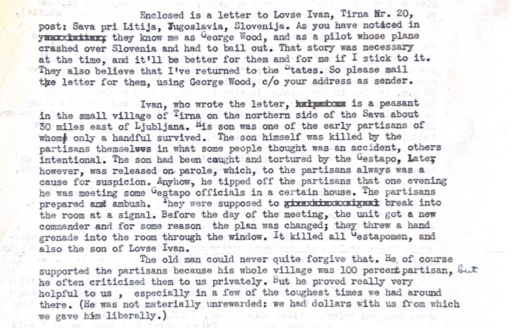

While I was able to map out some of Opapa’s experiences in Slovenia, I didn’t have many specifics. In Opapa’s 1946 letter to Laci, however, he offers some new, rather heartbreaking, information. He writes that he is enclosing a “letter to Lovse Ivan, Tirna Nr. 20, post: Sava pri Litija, Yugoslavia, Slovenija.” We don’t have the letter anymore (presumably, Laci sent it to Lovse Ivan), but Opapa does explain who Lovse Ivan is, and offers some new insight into his time in Slovenia.

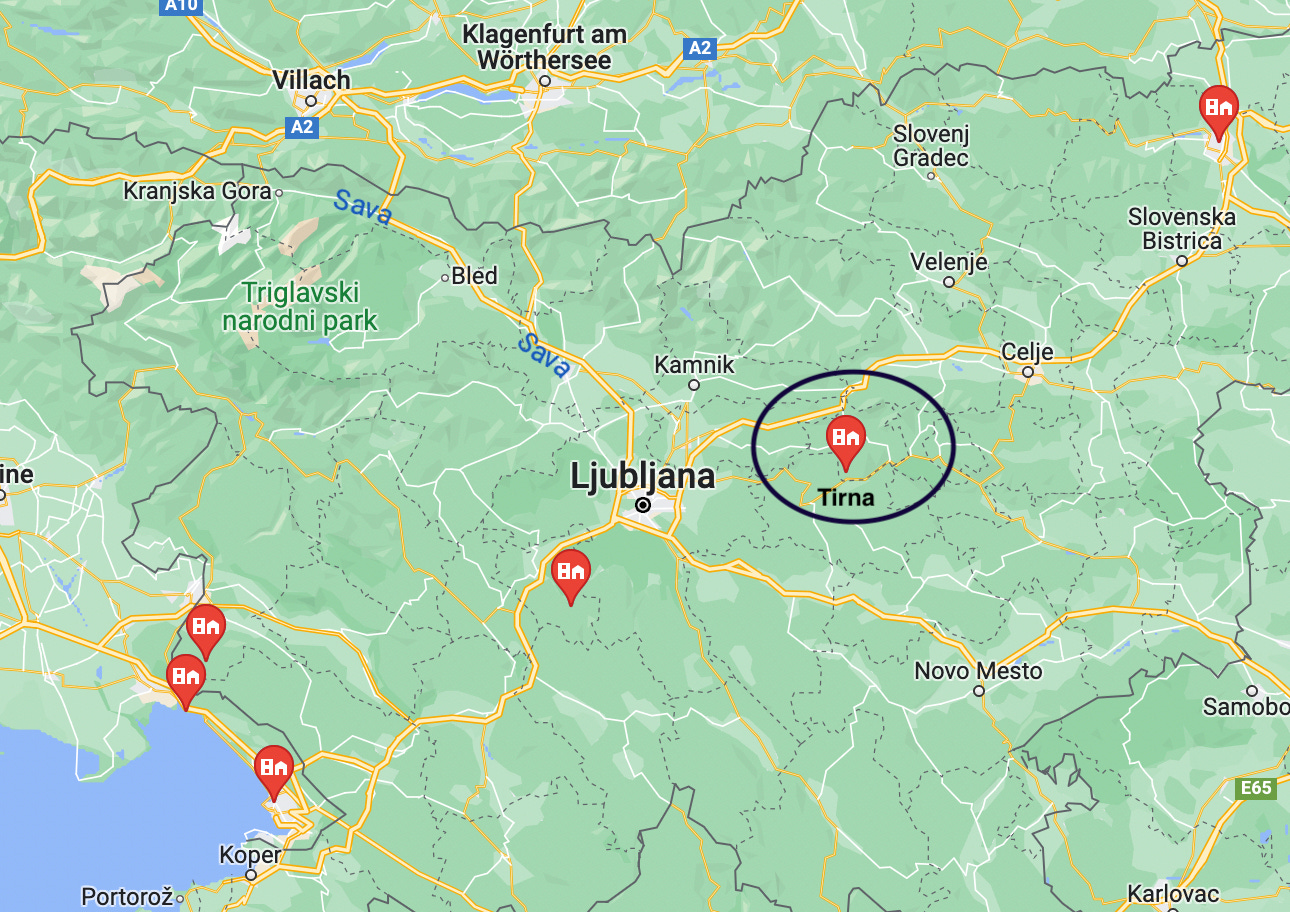

First, we learn about where Opapa spent time in Slovenia: in Tirna, a village “about 30 miles east of Ljubljana” on the “northern side of the Sava.” As you can see from the map below, Tirna lies about halfway between Maribor, where Opapa landed in February 1945, and Trieste, where he arrived in May 1945.

Second, we learn about how Opapa introduced himself to the Slovenes: they knew him as “George Wood” — his spy name. Opapa also told them that he was a “pilot whose plane crashed over Slovenia.” The Slovenes “believe that [he] returned to the States,” so Opapa asked Laci to send his enclosed letter to Ivan and mail it from the US, “using c/o George Wood” and Laci’s US address as the sender.

Third, Opapa relates a heartbreaking story about Lovse Ivan and his son, offering a window into life in Slovenia during the war:

[Lovse] Ivan…is a peasant in the small village of Tirna on the northern side of the Sava about 30 miles east of Ljubljana. His son was one of the early partisans of whom only a handful survived. The son himself was killed by the partisans themselves in what some people thought was an accident, others intentional. The son had been caught and tortured by the Gestapo. Later, however, was released on parole, which, to the partisans always was a cause for suspicion. Anyhow, he tipped off the partisans that one evening he was meeting some Gestapo officials in a certain house. The partisans prepared an ambush. They were supposed to break into the room at a signal. Before the day of the meeting, the unit got a new commander and for some reason the plan was changed; they threw a hand grenade into the room through the window. It killed all Gestapomen, and also the son of Lovse Ivan.

In this story, Opapa explains that Lovse Ivan’s son, who was one of the first Slovene Partisans in the village, was captured by the Gestapo. After he was tortured, he was “released on parole.” As a result, many of the other Partisans did not fully trust him (because he had been released rather than killed or imprisoned). Still, the son was feeding information back to the Partisans, including a meeting of “some Gestapo officials in a certain house.” The Partisans planned an ambush, but instead just threw a grenade in the house — killing not only the Gestapo, but also Lovse Ivan’s son.

According to Opapa, some people believed this was an “accident,” while others presumed it was “intentional.” Lovse Ivan, for his part, could never quite forgive the Partisans:

The old man could never quite forgive that. He of course supported the partisans because his whole village was 100 percent partisan, but he often criticized them to us privately. But he proved really very helpful to us, especially in a few of the toughest times we had around there. (He was not materially unrewarded: we had dollars with us from which we gave him liberally.)

In this final passage, we gain some insight into the relationship that Opapa developed with Lovse Ivan, and we also see the tragic messiness of war: Lovse Ivan “of course supported the partisans,” but he could also “never quite forgive” them for the loss of his son. Perhaps as a result of his mixed feelings, he “proved really very helpful” to Opapa, “especially in the toughest times.”

Opapa doesn’t say what the “toughest times” were, but life with the Partisans was certainly not easy. If the Partisans distrusted Lovse Ivan’s son — who was himself a local Partisan — they were probably deeply suspicious of Opapa, a Hungarian-speaking American officer with a cover story.