On February 7, 1945, Opapa finally got to enter the “action” of the war. It was a moment he had long waited for, but it did not go as planned.

As the Allied forces closed in on German territory, OSS Secret Intelligence agents were at the front lines, dropped into enemy territory to gain intelligence about the Nazi military, supplies, and plans. It was a dangerous assignment, and many agents never returned.

Opapa was part of a three-person team, known as “Team Dania”: together with his comrades Alfred Rosenthal and Paul Kröck, he planned to parachute into Freiland, Austria — Kröck’s home town. From there, they were to discover information about Nazi strategies and relay that information through radio to Allied forces back in Italy.

All three members of Team Dania were European and spoke multiple languages. Rosenthal was one of the five who, along with Opapa, requested transfer from the Operational Groups to Secret Intelligence. In their joint letter requesting transfer, he described himself in the following way:

T/5. Alfred Rosenthal. 32728515. Born Aug 1922. Dortmund-Hoerde, Germany. Education: graduated high school in Germany. Languages: Fluent German, Italian, English; fair French. Territory known: Westphalia, Northern Italy. Experience: 3 months in Divisional Intelligence school.

Paul Kröck, by contrast, had not transferred from Operational Groups. He was an Austrian who had deserted the German army years earlier. He fought with the Italian partisans before he was recruited into the OSS, where he joined Opapa and Al Rosenthal for their mission.

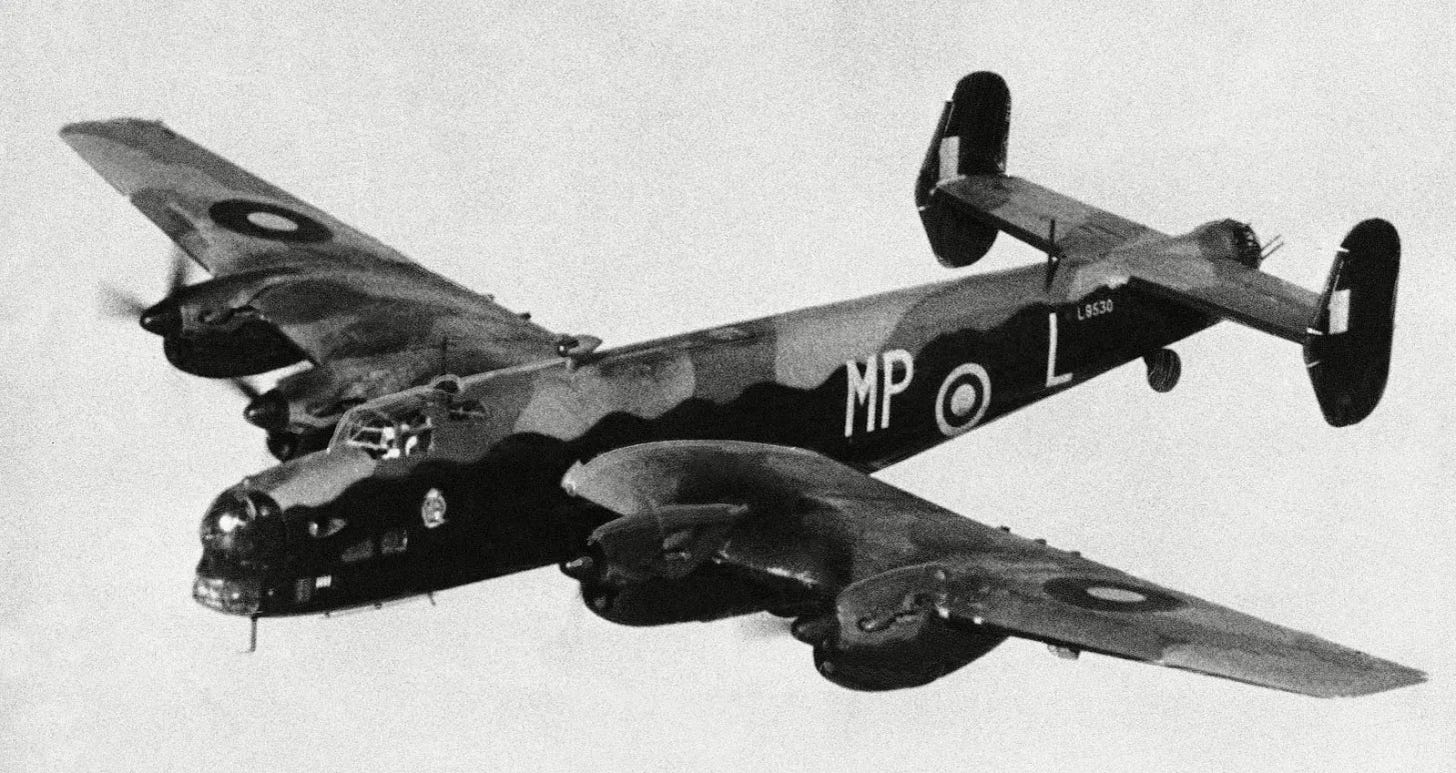

Team Dania departed in a Halifax bomber from Brindisi, Italy, during the night on February 7, 1945. The team flew north over the Adriatic sea and into Yugoslavia, waiting until they reached Freiland, Austria.

They never made it.

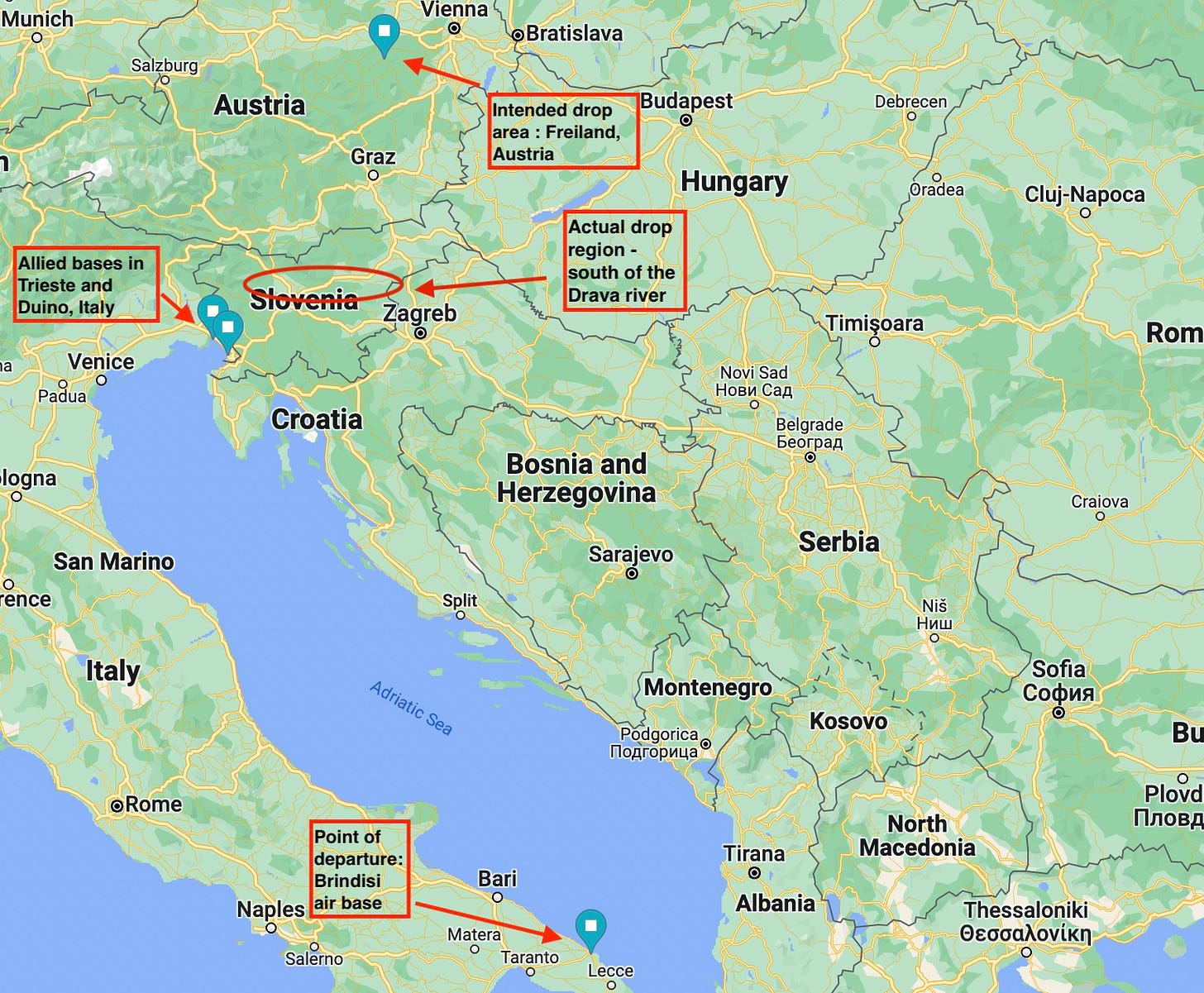

Opapa landed, instead, in a mountainous region in northern Yugoslavia, or current-day Slovenia. He eventually found Al Rosenthal, but not Paul Kröck. Here is a map showing their point of origin (Brindisi, south of Bari), their intended destination (Freiland), and their actual landing, south of the Drava river.

I remember Opapa talking about this. In my memory, he recounted how the pilot was on his 40th mission, and would be returning home to his family once it was completed. The pilot didn’t want to risk flying over enemy territory, he explained, so he dropped them in Slovenia instead.

In Opapa’s draft of his autobiography, he reiterated a similar narrative:

[T]he three of us jumped by parachute in what originally was designated to be a target in southern Austria. It so happens that the crew flying us -- it was their fortieth (last) mission, and we ran into some flak, some anti-aircraft fire, and I guess, I can't blame them -- they decided we were back in the hold, they didn’t need us, they just knew that there were three guys who were sitting back there waiting for the target and their communication with us was simply a "green light. ' When they pressed the button, we were supposed to jump. Well, they pressed the button a little too soon, so they could turn back a little faster, and we landed in very strange territory -- across the Drava River, actually in Slovenia, which was a surprise to us. We landed in very mountainous territory instead of a plateau, which was our original designated landing site. So we were separated in the air and never found the Austrian partner.

It turns out that Opapa’s story — about the pilot wanting to get rid of them — is not the dominant narrative. I was surprised to read the following account in a book by Franklin Lindsay, a former member of the OSS who included Team Dania’s mission in his book, Beacons in the Night: with the OSS and Tito’s Partisan’s in wartime Yugoslavia (1993):

“The night of February 7 was clear and moonless. The team, together with their equipment in six padded bundles with parachutes, climbed aboard an RAF Halifax bomber at the Brindisi air base. The Halifax was over the target area at 23:50 hours. Krock sat on the side of the hole used for dropping to try to identify any ground landmarks. On the first pass scattered clouds obscured the ground. The plane circles and returned 25 minutes later. This time the ground was clear and Krock, looking down through the hole, was certain he had identified the lights of Freiland a few miles from their target. The OSS officer in the plan later reported: “He was so sure of himselve he would have jumped there without waiting for the OK from the navigator.”1

A similar story is recounted in another book that describes the mission, Patrick O’Donnell’s Operatives, Spies, and Saboteurs: the Unknown Story of the Men and Women of World War II’s OSS (2004):

“As the team prepared to drop on the moonless night of February 7, 1945, Paul Kröck was certain he recognized the muted lights of Freiland through the “Joe hole” in their Halifax bomber.”2

There is a clear conflict here. Opapa insists that the pilot booted them out of the plane too early, while these accounts insist that it was all Kröck’s fault: he was so sure that he recognized Freiland from the air.

I have not gotten to the bottom of this story, but my guess is that both O’Donnell and Lindsay are basing their account on the report filed by the pilot and other OSS personell who were on the Halifax that night. If Opapa’s account is true, then they clearly filed a false (or misleading) report.

If I am correct, this is a real lesson in the problematic nature of official reports. The people who file them generally want to present themselves in the best light. In this case, Paul Kröck was the easy scapegoat because he was dropped far from Opapa and Al Rosenthal. He did, in fact, survive, but I don’t think this fact is included in the OSS records.

In any case, to be continued… !

Franklin Lindsay, Beacons in the Night: with the OSS and Tito’s Partisan’s in wartime Yugoslavia (1993), p. 171

Patrick O’Donnell, Operatives, Spies, and Saboteurs: the Unknown Story of the Men and Women of World War II’s OSS (2004), p. 257

I remember George telling me that he had a radio strapped around his body, and when he jumped the bomber was going so fast that the force of the airstream instantly ripped the radio out off his uniform. To me, this detail confirms what George told me on two different occassions: the pilots wanted to ditch George and his two comrades quickly and fly home because the bomber was running into heavy anti-aircraft flak and the Polish crew was on its final mission. Not only did the pilots drop the OSS men in the wrong place, they were flying far too fast for a safe drop . George said the loss of the radio compromised the mission - he could not communicate after he hit the ground. (A Halifax bomber could fly at 265 MPH; the maximum safe airspeed for a parachute jump is 120 MPH, according to Wikipedia.)

Late comment: I remember the similar story to you, the only difference is that it was a Polish RAF crew that told them to jump early because it was their last mission and they were running into flack..

Also I thought that the the Austrian member of the team was never heard of again.