A few weeks ago, I wrote a post about my great-grandfather, Árpád Gerbner, who was a teacher, linguist, and writer. Before World War I, he worked in a school in what is now Romania. Then, he moved to Budapest and started teaching there until the “White Terror” of the 1920s, in which conservatives (anti-Communist, anti-Jewish), led by Regent Horthy, took over the government and purged both Communists and Jews from many professions. Árpád lost his job at the school, and spent much of the rest of his life working at a bank.

I assumed Árpád never went back to teaching, but yesterday, I made some new discoveries — thanks to a new research assistant & translator based in Budapest.

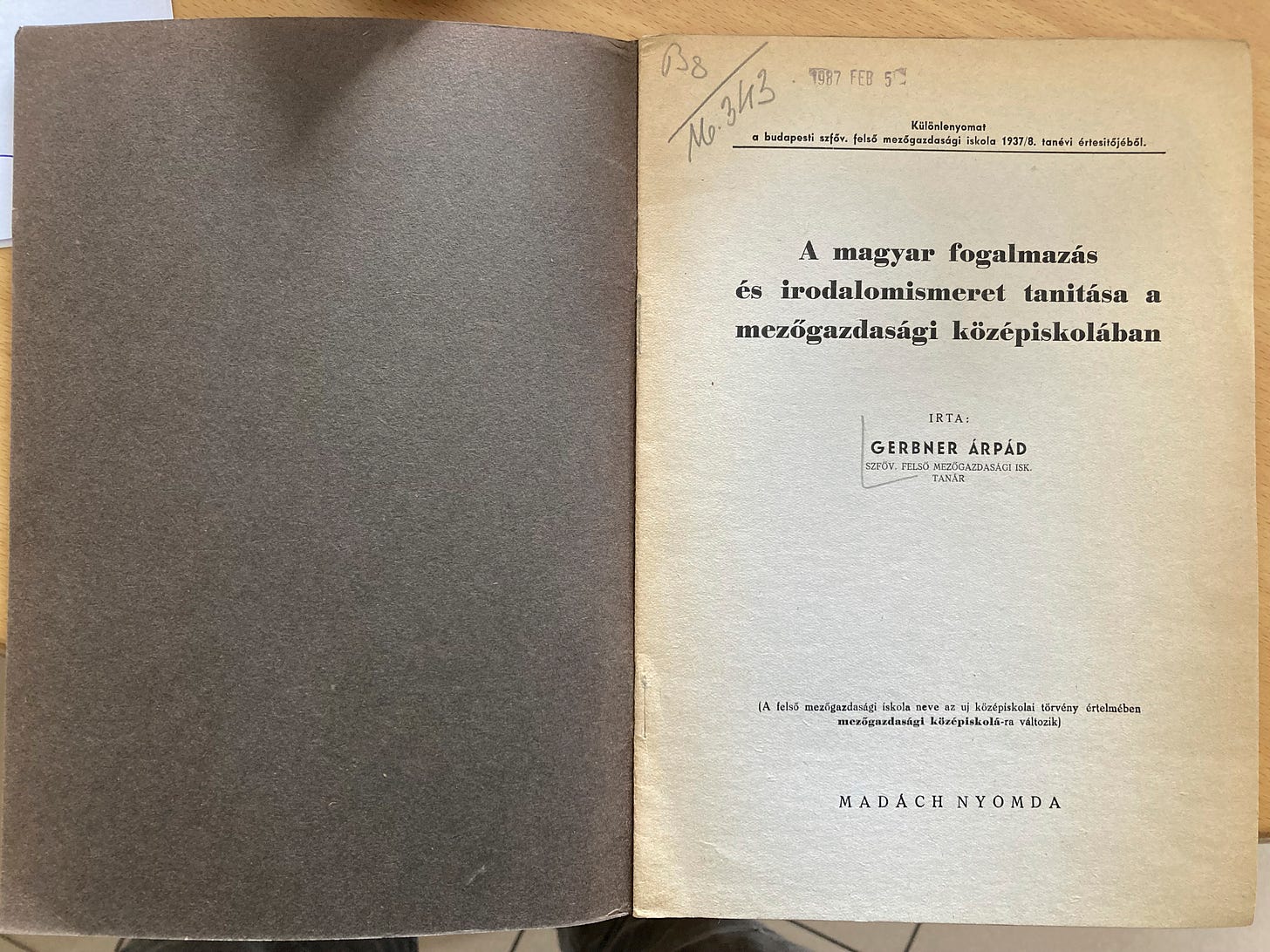

I knew that Árpád published a school textbook as late as 1938, but I couldn’t get a copy of it: the only existing one I could find was in the Magyar Mezőgazdasági Múzeum és Könyvtár, the Hungarian Agricultural Museum and Library. They didn’t have digital copies, and they only allow members examine their holdings in person.

My research assistant visited the Library yesterday. He sent me this picture of the entrance:

Inside, the librarian helped him identify not only the textbook, but also several other sources about Árpád in the 1930s! It turns out that he did eventually get another job as a teacher: from 1934/5 until 1939/40.

First, here is an image of the first page of his textbook. Really, it’s more like a pedagogical pamphlet rather than a textbook as we might think of it:

I haven’t had the text translated yet, but the title is “Teaching Hungarian writing and literary knowledge in the agricultural secondary school.”

Árpád published it while working at an Agricultural High School in Budapest: Budapesti Székesfővárosi Községi Felsőmezőgazdasági Iskola, which is located on what was then the outskirts of the city at Budapest, XIV. kerület, Kövér Lajos utca 5. Unlike Opapa’s high school, Eötvös Gimnázium, it no longer exists.

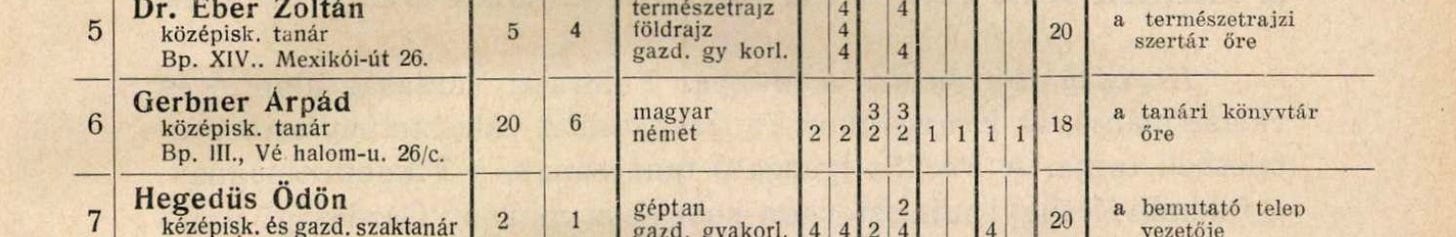

My research assistant found the yearbooks from the Agricultural High School, and they run from 1929-1942. I searched through them, and I can see that Árpád was hired in 1934, over a decade after he was forced to leave the teaching profession for the first time.

The yearbook gives some insight as to why Árpád was hired. It explains that the school was founded in 1926, but “in September 1933, our Main Maintenance Authority separated our school from the Civil School for Boys, and in September 1934 it gave a separate faculty to the Upper Agricultural School.” As a result, “the same teacher was no longer able to teach in two different schools at the same time, which made it very difficult to plan pedagogical work.” The result was that several new teachers were hired: “professors Andrasovszky István, Gerbner Árpád and Krisch Tivadar.”

Árpád taught Hungarian and German language and literature, and he was the “caretaker of the teachers’ and youth library.” He also served as the head teacher of the “Self-education circle.”

In 1935, Árpád wrote a short description of the activities of the “Self-education circle.” It seems they had some space issues due to “construction,” but they were still able to meet on several occasions. “We can recall with true joy,” he wrote, “the almost celebratory moments of healthy youthful spirit and a devout desire to learn, and the inspiring memories of debates that we have preserved in our records.”

During one Self-education circle, “Rába István and Sellei Sándor…read poems for the audience.” At another meeting, some students “gave celebratory speeches,” while others “recited texts on the occasion of the national holiday.” On February 2, 1936, “the young pupils organized a dance performance” and “performed Hungarian songs.”

The school seems underfunded and lacking proper facilities, but it makes me feel happy to know that Árpád was, in fact, able to teach again after being forced out of the profession due to political circumstances in 1920.

And yet, as we know too well, the political circumstances would change yet again. In 1938, the Hungarian Parliament passed the first of several anti-Jewish laws, which set quotas for Jews in several profession. The following year, in 1939, a more stringent set of anti-Jewish laws proposed by Prime Minister Béla Imrédy were passed. These placed further restrictions on Jews in several professions, especially finance, academics, and law.

The last mention of Árpád Gerbner comes soon after the Second Anti-Jewish law was passed. Here, he is listed in the 1939-40 school yearbook. There is just one reference to him:

It notes that he is a Hungarian and German teacher who teaches 18 hours per week. He is still in charge of the library. His address is Bp. III, Vérhalom-u. 26/c.

And then, he disappears from the records. No explanations, no notice, no mention whatsoever. We can only imagine the conversations that led to the termination of his appointment — the second time in his life that politics and anti-Semitism led him to be forced out of teaching.

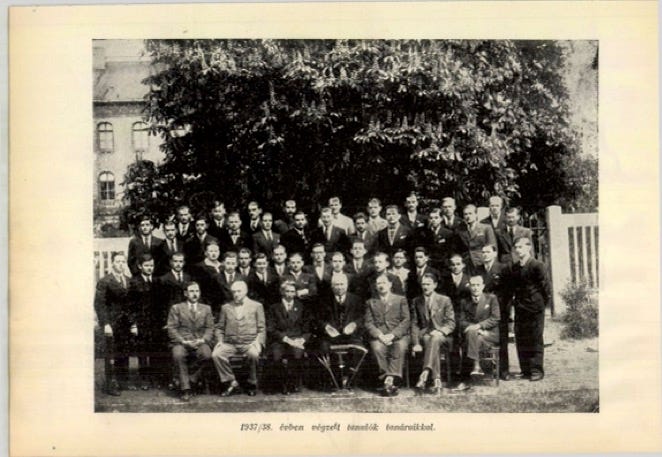

But I won’t leave you with that. Instead, let’s go back to 1937/8, where we can see him sitting in the front row, second from the left, head slightly tilted to the right, hands placed on his knees. It’s the fifth picture of him I’ve ever seen.

***

Nuts to crack:

How did the anti-Jewish legislation actually work? How was it implemented? Was there some type of committee formed to determine compliance?

Also, when did it go into effect? The second law was passed in April 1939, but Árpád seems to have been able to keep his job for a full year after it was passed.

Well, it is really great to learn that Arpad went back to teaching in the 1930's! I wonder why Opapa didnt tell me that (or he did and I forgot). Regarding his loosing his teaching job in 1920, what Opapa told me was that when the communists took over they got rid of the principal of Arpad's school and made him the principal. Then when the right wingers defeated the communists they kicked Arpad out of teaching altogether. Did Opapa tell you this as well?