Yesterday, I focused on photographs to offer a window into Partisan life. Today, I’ll focus on the descriptions of Partisan life written by Opapa and Franklin Lindsay, another member of the OSS who published a memoir of his time with the Slovene Partisans from 1944-45.

Opapa actually had Franklin’s book, which is entitled Beacons in the Night: with the OSS and Tito’s Partisans in wartime Yugoslavia, on his bookshelf when he died. Unfortunately, Opapa didn’t make any notes in the margins, so it’s impossible to know what he thought of the book.

In any case, the two men had some analagous experiences. Both Opapa and Lindsay, for example, went on long treks through the Slovenian winter, where they relied on the hospitality of peasants for food and shelter. This particular passage from Lindsay’s book struck me, with its’ detail about the importance of traveling with a spoon:

“When we came in the family immediately stood up, greeted us shyly, and motioned us to take their places. Each of us carried a spoon stuck in his boot top. It was often called the Partisan’s secret weapon, and when we first arrived with the Partisans we were cautioned never to lose our spoons; if we did we would starve to death. I dipped my spoon into the stew. It tasted marvelous. I knew that this was the family’s meal and if we ate it all they would go to bed hungry.” (420)

Franklin Lindsay also included some of his own photographs of his winter trek:

Both Opapa and Lindsay also encountered Partisan celebrations. In fact, Opapa’s first contact with the Partisans was a celebration. He wrote:

I went as far as I could up the mountain, and strangely, I heard music. Lo and behold, it was a Partisan brigade with a brass band, holding a dance. They were having a wonderful time and weren’t afraid of the Germans.

Lindsay, like Opapa, attended Partisan parties. Here is his description, this one in the only building with a roof in a newly liberated village in Slovenia:

“We were told there would be a Partisan dance that evening, and that we were expected to attend. It was held in one of the few buildings with a roof still intact. There were about fifty Partisans and civilian political workers, and the wine flowed freely. The dances were traditional Slovene dances, somewhat like American square dances, the music provided by an accordion and robust singing of Partisan song” (50)

It’s interesting that Linsday compared the Slovene dance to an “American square dance.” When I was looking through the Partisan photographs in Red Glow, I found this image of a Slovene dance in the mountains:

And this one of a Partisan musician:

Finally, both Opapa and Lindsay describe the destruction wrought by the Germans as well as other militias. Here is Lindsay:

“We spent the first night in a small village that had received horrible treatment at the hands of the Germans a few months before. The village church was a burned-out shell, and most of the houses were burned out as well, victims of a German sweep in force to retaliate for Partisan attacks on German garrisons and installations.” (50)

Similarly, this is what Opapa wrote, when he explained why he felt he could not trust the Slovene family that offered him dinner and a bed to sleep in:

They gave me dinner and offered a bed but I chose to sleep by the door. The reason was that I could not afford the risk of any member of the family going out to notify the nearby German garrison of my presence. And the reason for my fear was the knowledge that if the Germans find out that they were hiding an allied soldier, they would shoot the whole family and burn the entire village. (I had walked by enough burned villages to know that that was not an idle threat).

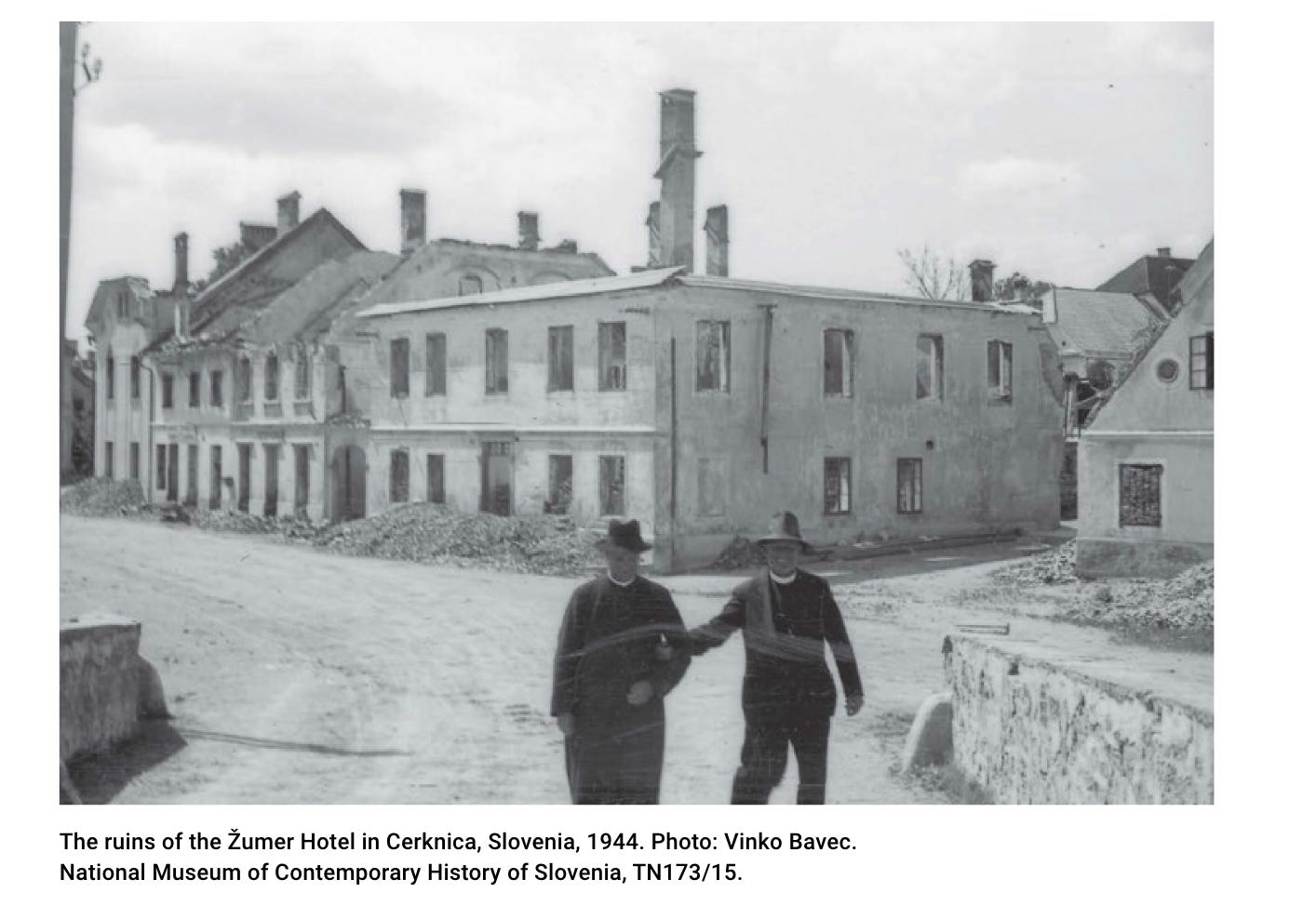

Partisan photography confirms the destruction.