Last week, I started investigating Opapa’s typewritten journal that runs from June 30-July 10, 1945. It’s very different from his 1944 journal, which was written by hand and recorded his reflections and thoughts. This one focused on his activites, and they are clearly related to his secret intelligence work for the OSS. I’ve been trying to decipher the significance of this document, and I’m going to spend the next few posts digging deeper into them.

On Friday, I wrote about the theme of car troubles. Today, I want to focus on a different topic: the aftermath of war in Trieste, where Opapa was stationed from July 2-July 10, 1945.

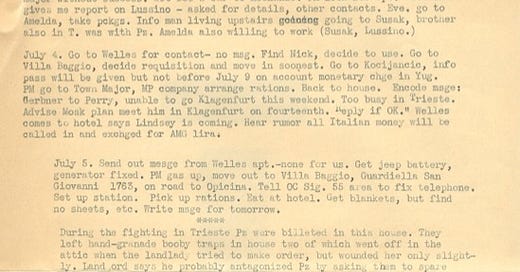

In between encoding messages, making visits to various contacts, and preparing to go on an expedition to Yugoslavia, Opapa mentioned the horrifying after-effects of war, as booby traps and hand-grenades continued to wreak havoc. Take this entry from July 5, 1944:

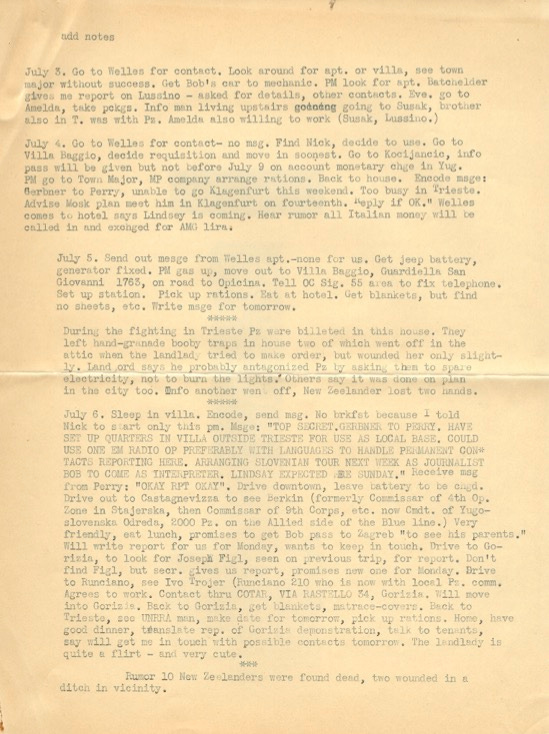

During the fighting in Trieste Pz were billeted in this house. They left hand-granade booby traps in house two of which went off in the attic when the landlady tried to make order, but wounded her only slightly. Landlord says he probably antagonized Pz by asking them to spare electricity, not to burn the lights. Others say it was done on plan in the city too. Info another went off, New Zeelander lost two hands.

In this passage, hand grenades left by the “Pz” (still trying to decipher who this represents) are left for unsuspecting civilians to find. The owners of this house in Trieste wonder if they had antagonized the Pz by “asking them to spare electricity” and “not to burn lights.” But their home was not the only one booby-trapped: Opapa notes that a “New Zeelander lost two hands” at another location. The next day, he wrote that there was a “Rumor [that] 10 New Zeelanders were found dead, two wounded in the vicinity.”

Random violence was not the only disorienting aspect of post-war Trieste. Opapa’s journal is filled with rumors and suspicions that were circulating. On July 4, for example, Opapa writes: “Hear rumor all Italian money will be called in and exch[an]ged for AMG lira.” (AMG stands for “Allied and Mility Government of Occupied Territories.”) The sense of uncertainty about the future is palpable.

There are also rumors about arms smuggling, which leads Allied headquarters to order a unit “to start extensive search of civilians, especially women with bundles, on all westbound trains fr Yug. to Trieste, as info has been received that arms smuggling has been going on and is planned to increase with the help of women.” Fascinating (and disconcerting) that headquarters is so focused on “women with bundles.”

Finally, while they are not necessarily “important,” I love the small details in Opapa’s journal that speak to the broader sense of disorder — as well as the banal aspects of everyday life — that existed in the immediate aftermath of the war. For example, on July 5, he wrote that he got “blankets, but [could] find no sheets, etc.” The next day, when he went to Gorizia, he “g[o]t blankets, matrace-covers.”

Even in the chaos of the post-war period, people had to sleep.

I am pretty sure that Pz means Partisans.