Looking back years later on his time in North Africa, Opapa would recall that he spent “an extended and very pleasant period in Algiers.” He gained “further training but basically was waiting for a mission.”

Opapa’s diaries at the time, however, paint a less rosy picture. While he did mention going to the beach frequently, the lack of an active mission in the war led to low morale.

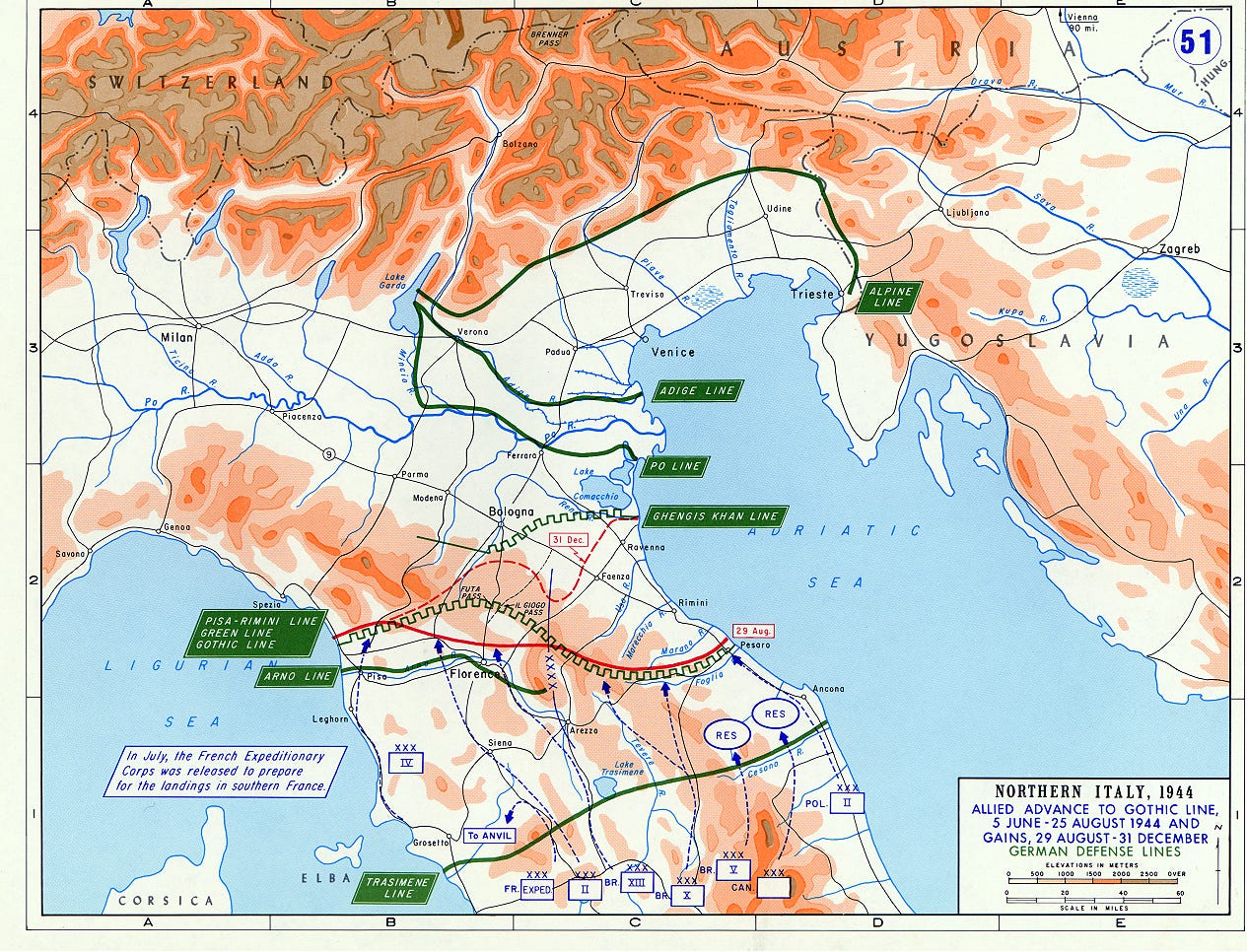

After the false promise of a mission to France, Opapa finally departed Algeria for Italy in October 1944. By that time, the Allied forces were already in control of most of the country, though pockets of Axis control remained. The liberation of Italy had begun in July 1943 with the Allied invasion of Sicily, followed in September 1943 with the capture of southern Italy and Naples. Rome was under Allied control by June 4, 1944, followed by Florence, Pisa, and Bologna in summer 1944.

By fall 1944, Allied forces were concentrating on gaining control of what was known as the “Ljubljana Gap”: modern-day Slovenia, located between Vienna and Venice, which was then part of Yugoslavia. It would be another six months before victory was declared in this area, and this was where Opapa would eventually find himself behind enemy lines in 1945.

When Opapa first arrived in Naples in the fall of 1944, however, he continued to chafe at his inability to participate in the real action of the war. He wrote in his diary:

“At the Repl-Depot [Replacement Depot] near Naples. We got here from Africa few days ago. Have written request to C.O. of O.G. to give us mission - no result. Confusion, rumors. Every day we’re after lt. Machierman to do something for us. Tomorrow we’re going on a pass to Caserte[?] to try to see Col. Livermore. I have no ambition to do anything except try to get out of this rotten setup. Don’t feel like writing or even reading.” (Gerbner Diary, October 20, 1944)

Rife with dissatisfaction – with his “rotten setup,” – Opapa was despondent. He didn’t feel like “writing or even reading.”

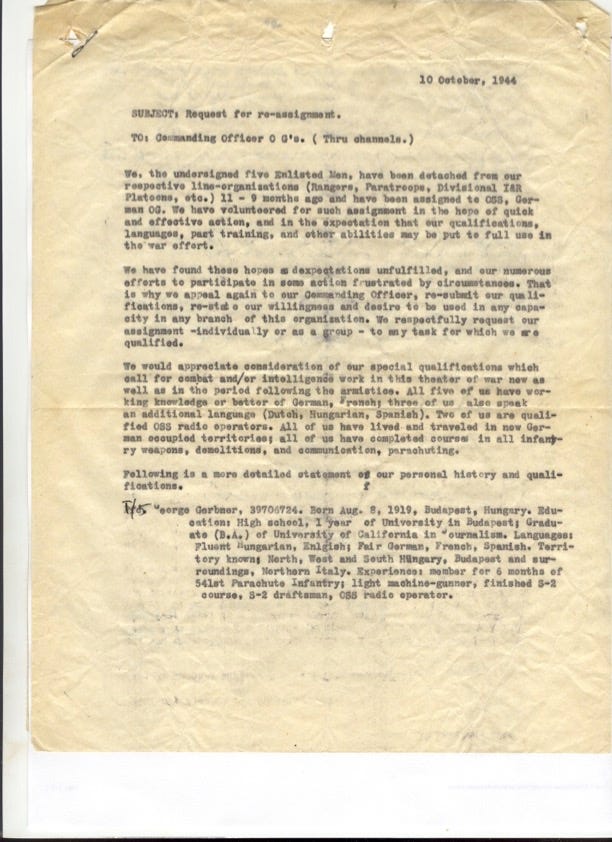

He was not the only one. Together with four other members of the OSS, he wrote a letter requesting reassignment.

The letter began:

“We, the undersigned five Enlisted Men, have been detached from our respective line-organizations (Rangers, Paratroops, Divisional I&R Platoons, etc.) 11-9 months ago and have been assigned to OSS, German OG. We have volunteered for such assignment in the hope of quick and effective action, and in the expectation that our qualifications, languages, part training, and other abilities may be put to full use in the war effort.”

It was a talented group: all five had “working knowledge or better of German, French; three of us also speak an additional language (Dutch, Hungarian, Spanish).” Two – one of whom was Opapa – were “qualified OSS radio operators.” All five men had “lived and traveled in new German occupied territories,” and all of them had completed training in “infantry weapons, demolitions, and communication, parachuting.”

The letter including a brief description of each of the five. Opapa’s reads:

“T/5 George Gerbner, 39706724. Born Aug. 8, 1919, Budapest, Hungary. Education: High school, 1 year of University in Budapest; Graduate (B.A.) of University of California in Journalism. Languages: Fluent Hungarian, English; Fair German, French, Spanish. Territory known: North, West, and South Hungary, Budapest and surroundings, Northern Italy. Experience: member for 6 months of 541st Parachute Infantry; light machine-gunner, finished S-2 course, S-2 draftsman, OSS radio operator.”

Another one of the five, Hans Wynberg, had been with Opapa in North Africa, and they had both completed the training in OSS radio operations near Algiers. Wynberg, like Opapa, was a Jew who fled his homeland (the Netherlands) and relocated to the Unites States. He would later learn that his parents and younger brother had all perished in a concentration camp. Also like Opapa, he would become a University Professor, though in Chemistry rather than Communications.

In an impassioned plea, the five Jewish refugees asked to be placed into the action of war. In their letter, they barely masked their exasperation as they appeal “again” to their “Commanding Officer,” and “re-state[d]” their “willingness and desire to be used in any capacity in any branch of this organization.”

It took a while, but on November 6, 1944, Opapa wrote in his diary that the letter “had worked.” The five men were asked to see the Colonel, and then interviewed by Captain Whithinghill of S.I. (Special Intelligence) who got our transfer through.” They were then sent to Bari, Italy for a “refresher course” in radio school. (Opapa diary, 6 Nov. 1944)

Opapa was relieved to be transferred to SI, and looked forward to active service. Unfortunately for historians, as his activity increased, his diary entries decreased. Or rather, they shifted: he started to use his diary to take notes from his “refresher” course in Bari.

One of those five men, Frederick Mayer, talked about this in an interview with the Shoah Institute (segment 45). He also went to Bari for further training.

https://vha.usc.edu/testimony/33771?from=search&seg=45