High School Notebook

Rimóc and Hollókő: 1930s and 2024

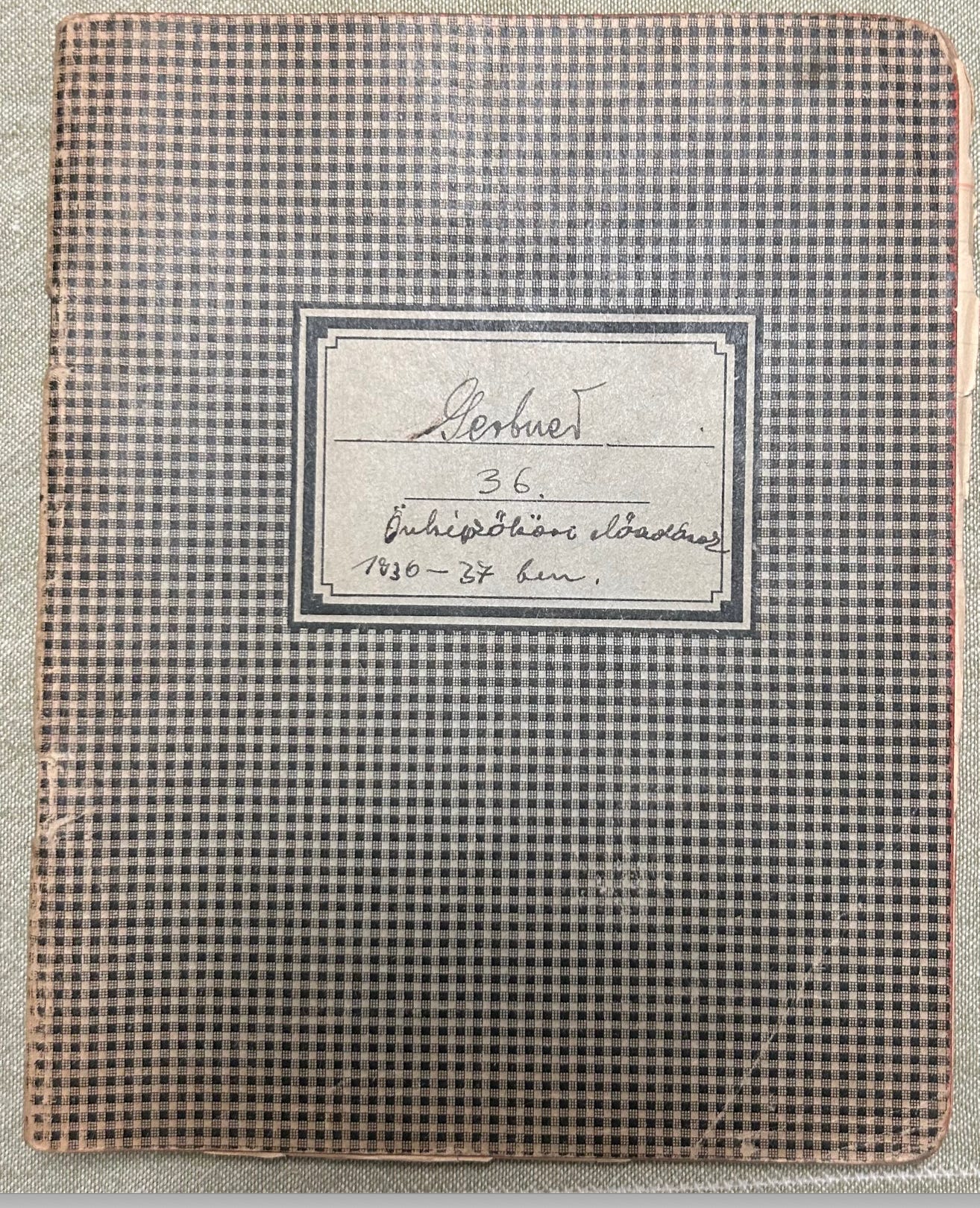

Last year, when I was going through boxes of my grandfather’s papers at my aunt and uncle’s house, I came across this notebook, dated 1936-37.

The title on the front of the notebook is “Önképzőköri előadások,” which means “Self-study group lecture.” Inside were Opapa’s notes for a presentation he gave in high school about Rimóc, the rural town in northern Hungary where he spent his happiest summers as a teenager.

Rimóc is home to the Palóc people, ethnic Hungarians with a distinctive style of dress and language. As a teenager, Opapa traveled to Rimóc regularly, where je lived with a local family and came to love the culture and the customs of the place. He stayed in touch with people from the village after he left for the United States in 1939.

As I started reading Opapa’s presentation notes, I realized that they were based on photographs he took in Rimóc — and that these were the same negatives I had recently developed and made into digital files. Each description in his presentation corresponded to a photograph.

I tried to match up the photographs with the descriptions from his presentation, but it was harder than I had anticipated. So I’m sharing one of his descriptions, and a few photographs that might match:

5th picture

Bride.

She is still young, only her hair-do is different from the unmarried girls. From the age of 30, they only wear blueprint (kékfestő - a Hungarian blue dye) or black clothing. A nice szakácska (type of apron) with rich patterns.

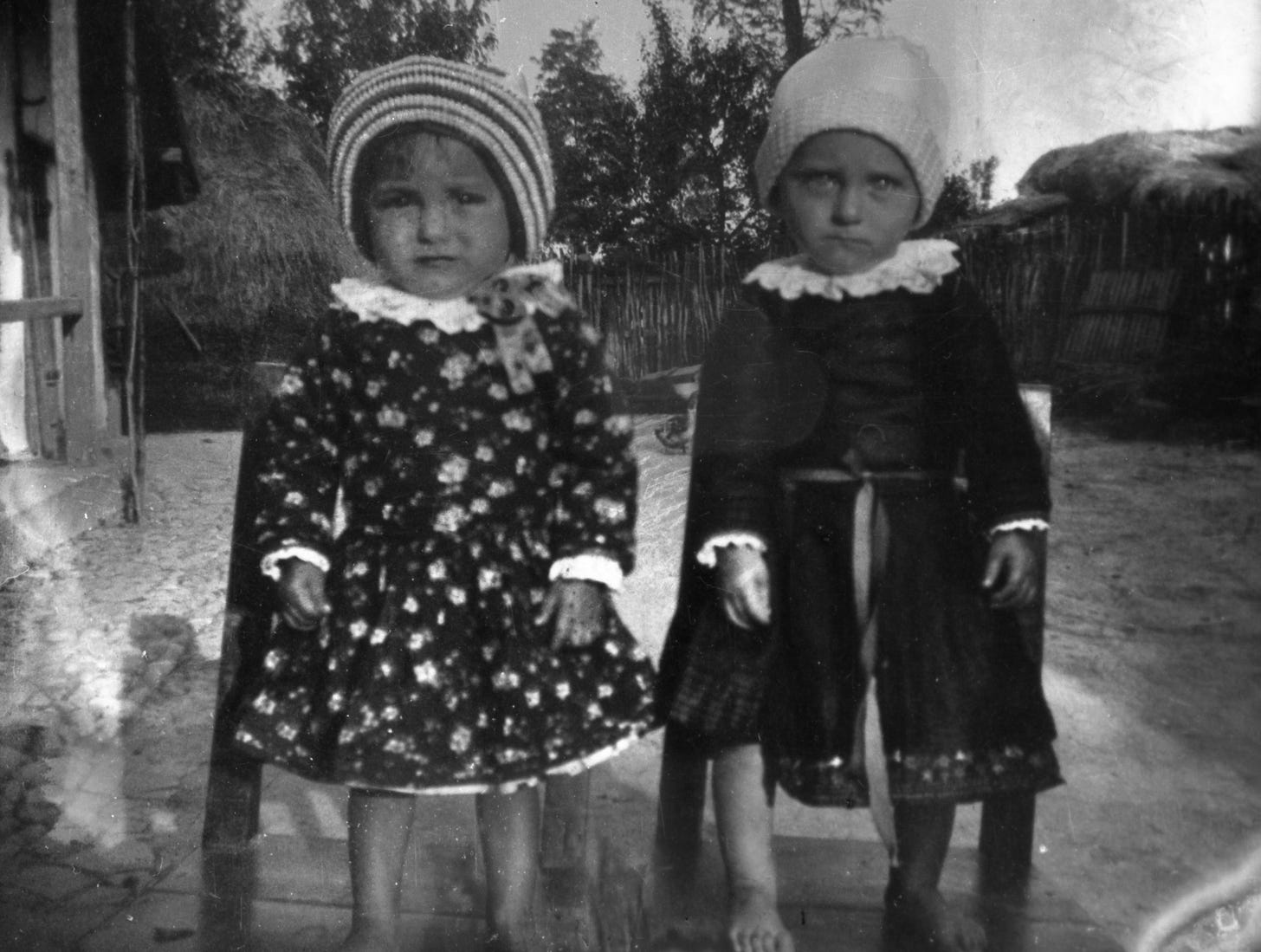

And here is one of several photographs of Opapa in Rimóc in 1936 or 37, this time with two young Palóc girls in traditional dress:

Since Rimóc and Hollókő were so important for my grandfather, I made it a priority to visit the towns during our family research trip to Hungary last month. I wanted to see the Hungarian folk villages that had inspired my grandfather as a teenager.

Today, Hollókő is a UNESCO World Heritage site and as a result, it is a “pristine” village — geared towards tourists. You park your car before the entrance to the town, and then you can walk through the streets, visiting a variety of museums and small shops. It is very cute, and also very manicured. While you can purchase “traditional” Palóc goods around town, it has changed dramatically since my grandfather was there in the 1930s. It is technically still an “inhabited” village rather than an open-air museum, but there are no locals wearing traditional dress, and it feels like a tourist destination, albeit a beautiful one.

Still, I was curious to see if I could find anyone who might know the people in my grandfather’s photographs, so at one of the museums, I asked the woman working there whether she recognized anyone in his photographs. We spoke to each other with the help of Google Translate, since I can’t speak Hungarian and she couldn’t speak English. She told me that she only moved to Hollókő in the 1980s, but she offered to introduce me to someone who was from Hollókő — a word that was translated into English as a “Ravenstone,” because that is the meaning of “Hollókő” in Hungarian.

We walked down the street to talk to an older woman, who was born and raised in the village. I showed her the letters my grandfather had received from one of the “Ravenstones” back in 1939, and also photos of many of the Palóc people who lived there. We spoke for a while, and had a nice conversation. But alas, she said that she was too young to remember anyone.

After a lovely few hours in Hollókő, we decided to drive to Rimóc. My grandfather spent more time in Rimóc than Hollókő, and I hoped we would have more luck. Perhaps, since it was not as much of a tourist destination, we might find someone who remembered someone from the photographs. It was a long shot, but I was curious to at least see the place.

Unfortunately, Rimóc was completely deserted. No one was on the streets, and — more strikingly — it did not look like a “Palóc” village at all. Without the UNESCO label and the tourist industry, it seemed more like a typical village — in fact, the most remarkable thing about it was the “I heart Rimóc” sign when you arrive in town:

The experience made me think about cultural change, what it means to call something “traditionally” Hungarian, and the effort to “save” so-called “national” or ethnic cultures. As a historian, I am always suspicious of the word “traditional”. Usually, “traditions” are what you call something when you want to mark a practice as distinct from the “modern,” and the word is saturated with cultural nostalgia that implies an unchanging past. But cultures, and customs, are always in flux, so nothing is ever really “traditional.”

At the same time, however, I do appreciate the effort to understand, preserve, and celebrate “traditions” that are no longer regularly practiced. I see my grandfather’s teenage desire to “preserve” and “collect” Palóc songs, traditions, and dress — and to capture them in photographs — as part of his love for his homeland. I also believe his interest was connected to an appreciation for agricultural labor and a critique of class-based urban society during a period of change, modernization, and urbanization. Finally, I think his summers in Rimóc were part of a larger effort to appreciate — and record — oral cultures during a time that saw the expansion of “mass media,” including radio and “talkies.”

I’ll write more about Opapa’s love of folklore moving forward, but I’ll end with the report I found in his school yearbook from 1937 about the presentations he gave based on his time in Rimóc:

Here we would like to mention that Gerbner György, student of Class 8B, scoutmaster gave several lectures in the youth clubs, based on the material he collected last year at the camp in Hollókő; at the literature youth club he presented the rituals of a Palóc wedding, then a folktale he had collected; at the music youth club he gave a lecture on Palóc music and he made the presentation more appealing by playing Palóc folksongs on a zither; and at the art youth club he gave a presentation about Palóc folk art and he received the Grand Prize of the Art Youth Club for this work. This versatile work with which he showed the results of his activities at the summer camp to the students at the school and contributed to the students’ knowledge about their own nation shall be set as an example to others.

As I read this description, I realize that one thing I am missing, in doing this text-based research, is the sound of the zither, and of course the very essence of oral storying: hearing the story passed down. I’m glad I have memories of Opapa talking about Rimóc when I was a child, but I wish I could ask him to tell me more, in person.

Alas, I am left with just visual evidence: text and photographs. So I will end with one more photograph of Opapa from his summer in Rimóc. He is wearing his scout uniform, standing next to his host father:

***

Nuts to crack:

Going through Opapa’s photographs of Rimóc and Hollókő, I found this one that I wasn’t sure how to interpret. It looks like a religious procession?

And here are some cute kids, I just love the outfits:

Bad Dad catching up on my e-mails. Great article, and it was very interesting to see Holloko and Rimoc (Rimoc not as much). I wonder what it was like for Opapa to go to these places. Hard to imagine since I would think that life in Rimoc was far more different than life in Budapest than life in, say a tiny town in the hills of West Virginia would be today from Philadelphia (due to the lack of a unifying mass communications system). Obviously.

Dear Katie,

This post is just wonderful. Your description of the tourist aspects of today's Holloco (I don't have Hungarian punctuation) put me in mind of Americans visiting Colonial Williamsburg. Somehow you know the place didn't look or feel the same back in the day as it does now. And I'm intrigued by Opapa's high school paper and his presentation of his experiences. Years later, though his appreciation of the "traditions" and culture of the two towns likely took on deeper intellectual meaning, it seems possible that his papers for school were ruminations on what he did last summer. I wondered if any of the distant cousins or friends who have stayed with you over the years at PLP had the same kinds of reflections on the traditions of nodding to everyone, summer tea parties with specific protocols, hiking to the big rock (?) and other landmarks, the church grove, finding red efts, square dancing, team games, etc. - all of which would feel foreign and kind of exotic to urbanites. And then they would go home knowing that the things they had experienced were not at all foreign to the people who "lived there" and were going to continue. We will likely never know the answer but I am thoroughly enjoying the possibility.