Family, Memory, and Secrets

Some reflections

I’m going to write about something I’ve been hesitant to discuss in my previous posts. It’s not about my grandfather — at least not directly. It’s about my grandmother, Ilona, who we always called Omama.

As a kid, I felt very close to Omama. I was her first grandchild, and she lived nearby, in the suburbs of Philadelphia. When I was in preschool, my grandmother would pick me up once a week and take me to lunch in Suburban Square. These excursions left an indelible impression on me, and I still feel deep nostalgia for the scent of my grandmother’s perfume, and the feeling of the maroon cloth seats in her 1980s Peugot sedan. In fact, any time I see a Peugot, I think of my grandmother.

My grandmother liked to have deep, meaningful conversations, and to ask probing questions. As a child, this made me feel like she really cared about me; like she really wanted to know and understand me.

My relationship with my grandmother started to change when I was a teenager. Not because I was a teenager, but because my grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Over the years, once she forgot who I was, I would have small talk with her — she asked me where I was from, who my parents were. But by the end of her life, she spoke only in Hungarian, and there were no more conversations.

My grandmother connected with people deeply, but she was also a private person and she did not like surprises. She kept certain information about herself locked away. Her age was a mystery to her children and grandchildren, and she would not talk about her experiences during the war, except in broad outlines. She did talk about theater, and her childhood in Vienna, and her love of classical music.

As I do research on my family, I try to be very respectful of my grandparents and their legacy, and I am particularly protective of my grandmother. This is not only because I felt a deep kinship with her growing up, but also because — unlike my grandfather — she was not trying to write an autobiography when she died. She was not planning to publish her own story.

This long prelude is to say that I have struggled with how to write about my grandmother: should I keep the same information private that she kept private? Or has the time for that passed?

I remember my parents struggling with this after my grandparents died in 2005: they discussed, with my uncle and aunt, whether to put my grandmother’s real birth year on her gravestone (1918) or whether to use the date she used (1921). They decided to go with her real birth year.

I’ve decided to make a similar decision: I want to write about my grandmother with respect, but I also don’t think I need to keep the same boundaries that she did. She had her reasons — very valid reasons — for keeping certain things private. But things are different now.

So: what am I actually talking about here? Well, a few months ago, my sister Emily and I discovered that my grandmother — like my grandfather — was Jewish. We found her birth certificate in the archives of Israelitische Kultusgemeinde in Vienna, along with her parents’ wedding certificate. And if that wasn’t enough of a surprise, when I looked farther back — at my great-great-grandparents — I learned that Omama’s grandfather was a well-known rabbi named Gyula Klein.

Gyula Klein was born in 1850 in what is now Serbia (at the time, it was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire). He was educated in Vienna and Tübingen and became a rabbi in Szigetvár and, later, Óbuda, a suburb of Budapest. In the 1870s and 80s, he wrote histories of the Jewish communities of Szigetvár and Óbuda, and published articles about Talmudic literature. Most notably, he was the first person to translate the Talmud into Hungarian.

When I discovered this connection a few months ago, my questions about my grandmother started to change: I began to think not only about her intentions and her secrets, but also about Gyula Klein — what stories would he want his descendants to know?

With that perspective, I became more at ease with telling a story about my grandmother that she chose not to reveal. The story of her Jewish heritage does not just belong to her, but to her ancestors and also to her descendants. I want to know more about it, and to understand why she chose to make it a secret.

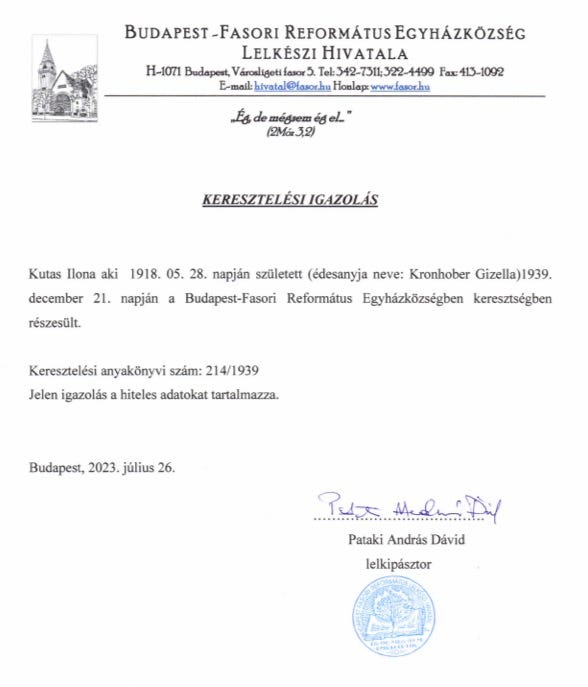

And on that note, I’ll end with a source that explains, at least in part, why she kept this part of her life a secret. It’s a source that Emily found yesterday: my grandmother’s baptismal certificate, dated December 21, 1939. It’s from the Reformed Church in Budapest, which was close to her home on Rippl Ronai.

This document explains something that has been very perplexing, ever since we discovered Omama’s Jewish heritage: how she did she survive the war in Budapest, when so many other Jews — including my great-grandfather — were murdered?

It turns out that she, along with thousands of other Hungarian Jews, decided to turn to Christian baptism in the face of rising anti-Jewish legislation. The date of her baptism, in December of 1939, came just a few month after the second set of anti-Jewish laws were passed in Hungary, severely restricting the livelihoods and economic stability of the Hungarian Jewish population.

As this document reveals, Omama had very good reasons to keep her Jewish heritage a secret. Thousands of others did the same. But her decisions do not need to be eternal. They are part of a longer story that is not yet over.

***

Nuts to crack:

When and why did Omama’s father, Andor Kutas, change his last name from Klein to Kutas? Was it primarily to “Magyarize” his name, ie make it more Hungarian? Or was it to distance himself from Judaism?

Was Omama raised Jewish, or had her family assimilated to such a degree that she did not identify as Jewish, even as a child?

Katie, this is such a beautiful tribute to the love you feel for your Grandmother. Your style of writing is so clear and touched my heart.

I’m looking forward to reading more of your posts and learning how your Grandmother

navigated a terrible time for Jews. It must have been very frightening to face what she needed to do to survive It is sad that Jews still have to face so much antisemitism.

I appreciate all of the unfolding you’re doing, both in negotiating your own intentions and inquiring about hers. The uncertainty you’re showing is one of my favorite parts about teaching/learning histories, and it’s so cool to learn abt your process in real time.