In my Graduate seminar on the “Archive,” I always assign a book by the historian Arlette Farge entitled “The Allure of the Archives.” Originally written in French, it describes the mysterious and enticing space of physical archives: the sound of researchers entering the building; the quiet competition for the best desk locations; the smell of 18th century paper; and the pride that comes with knowing how to correctly submit call slips and examine manuscripts.

Sean asked me yesterday to write a little bit more about the archive, and who is here, and where I am. So today, I’m going to do that — somewhat in spirit of Farge’s “Allure of the Archives.”

First, some pictures of my daily routine: entering the behemoth of a building in College Park; and sitting at my desk in the reading room.

Since Covid (and having children), it’s been more difficult to have time to visit actual archives. But today, I finally feel like I’ve “figured out” the National Archives in College Park, MD. I know how many records I can call up together from each stack areas; I have gotten to know some of the archivists, who have provided invaluable insight; I know where the gloves are located in case I come across photos in my stacks of paper; and I have learned how to get the “declassification slug” required to take photos of formerly classified materials (this is the small piece of paper you see in my photos of documents). These are the small feelings of triumph that accompany the alternately riveting and frustrating world of archival research.

The greatest feeling of triumph, however, is opening up a file, and feeling the thrill of excitement that you’ve discovered something — perhaps something that you were hoping for, or perhaps something you never expected to see. I had a few moments of that today. One was when I opened up this box of “General Records” of the OSS, and examined the file labeled “Gerbner, George.”

This was a good folder: it complemented and expanded my understanding of Opapa’s 1945 mission to Austria/Slovenia, and offered new information on what he did in the summer of 1945, when he was traveling between Trieste, Slovenia, Salzburg, and Budapest.

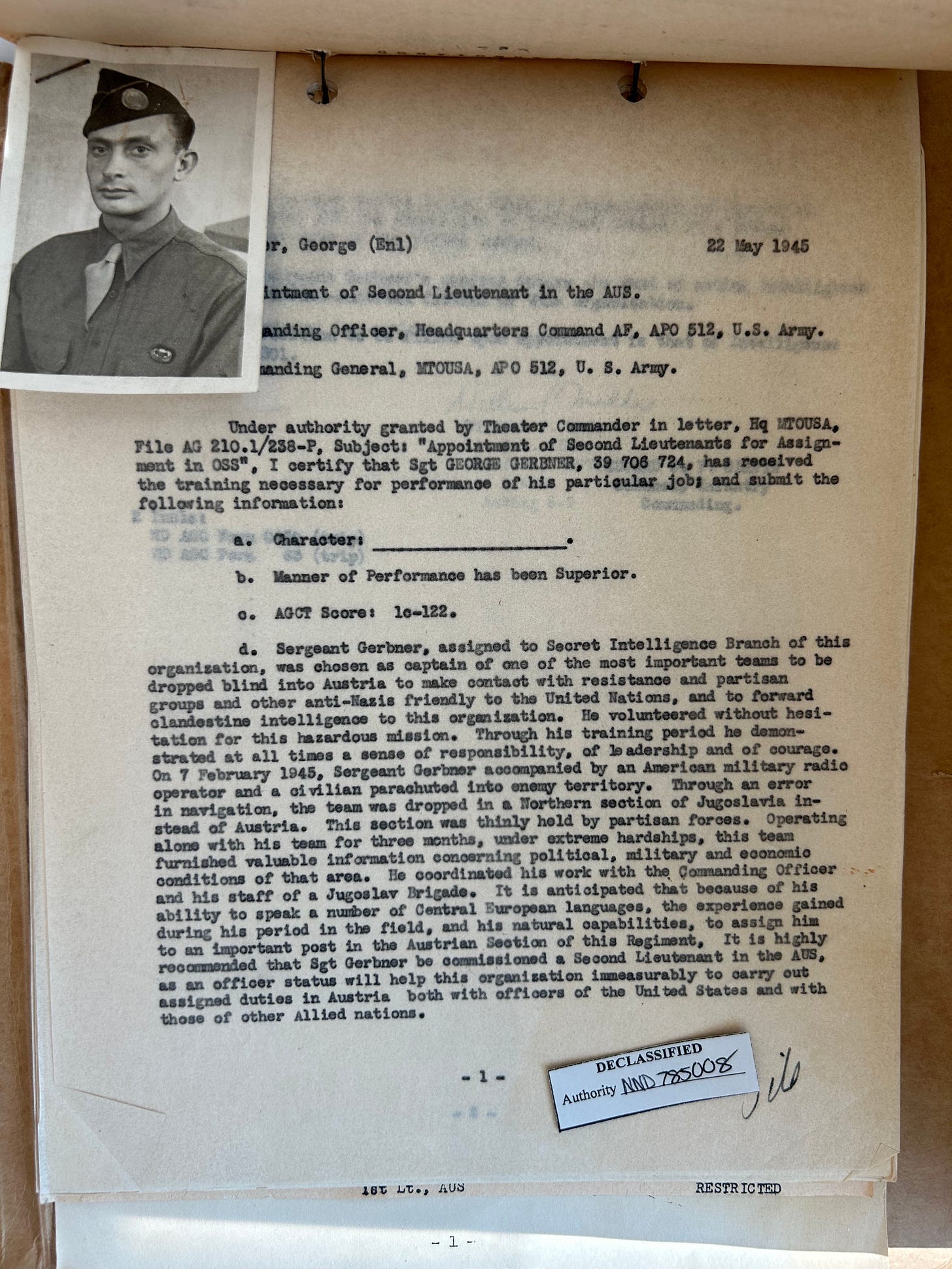

There was one point, flipping through the pages, when I actually exclaimed “oh!” because all of a sudden, I found myself looking at a photograph of my grandfather that I had never seen. Photographs are rare in these files, and it was jolting to see this one:

In addition to the photograph, the text of the record was lovely, in that it offered an external evaluation of Opapa’s record “in the field.” According to this recommendation,

[Gerbner] volunteered without hesitation for this hazardous mission. Through his training period he demonstrated at all times a sense of responsibility, of leadership and of courage…It is anticipated that because of his ability to speak a number of Central European languages, the experience gained during his period in the field, and his natural capabilities, to assign him to an important post in the Austrian Section of this Regiment. It is highly recommended that Sgt Gerbner be commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the AUS…

From this, we learn that Opapa earned his promotion, and his position arresting Hungarian war criminals in the Austrian office, thanks to his bravery during the Dania Operation.

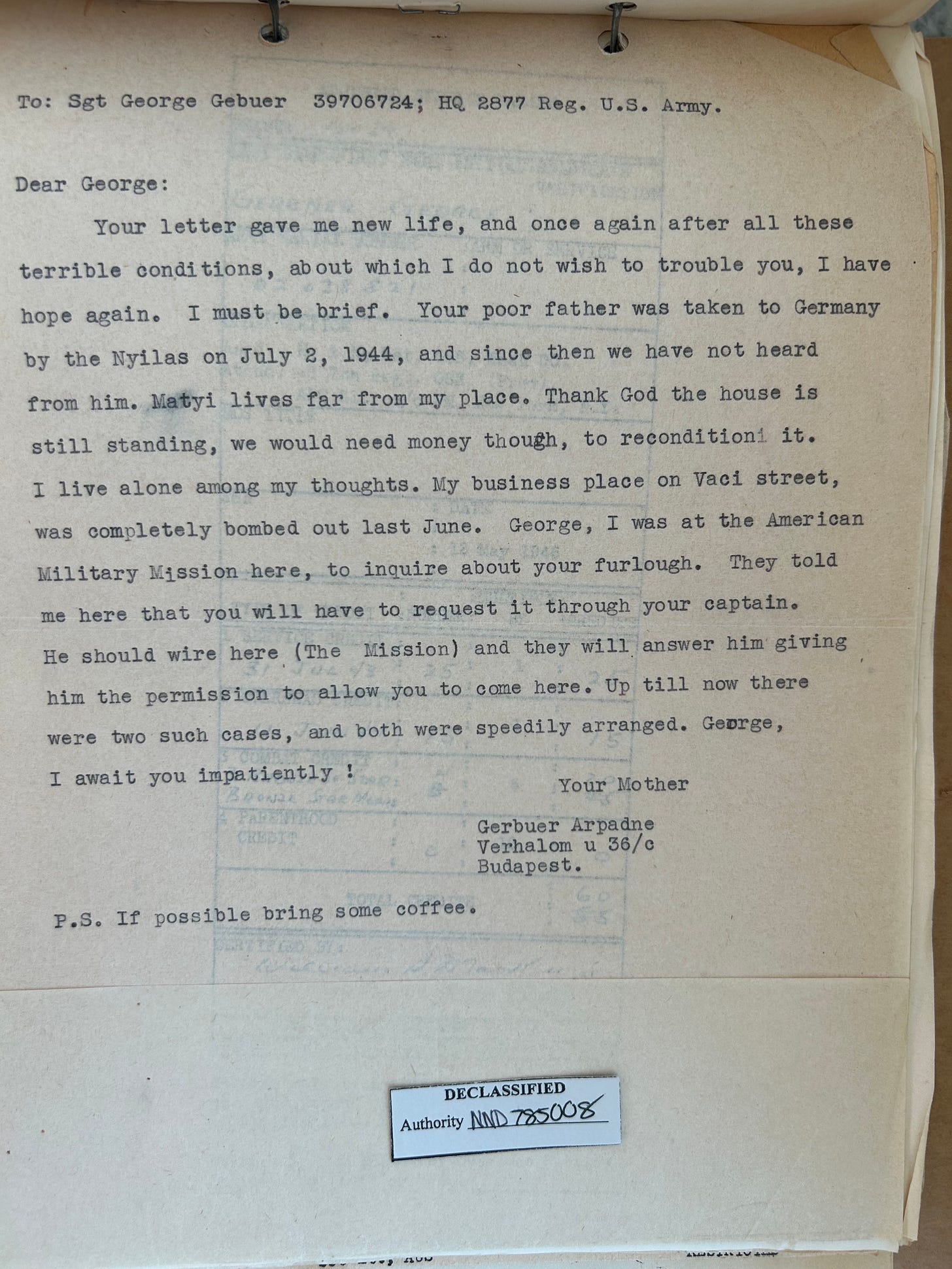

In the same folder, I found one other document that took my breath away. It was the missing English-language translation of the devastating letter that Opapa received in July 1945. The original letter — written by Margit Gerbner in Hungarian — informed Opapa that his father, Árpád Gerbner, had been deported in July 1944, and was still missing. The Hungarian letter was in Opapa’s personal files, along with a cover letter, written on Military stationary, saying that an English translation was attached.

Well, there was no English translation in Opapa’s files. The English translation, it turns out, had made it into the National Archives, Record Group 260, Entry No , Box #8, in a folder called “58 Gerbner, George.” Here it is:

In this case, we know exactly what happened: the original letter, along with the cover letter, were passed on to Opapa, while the OSS kept the English translation of Margit’s letter for their files.

And there it remains.

***

Nuts to crack:

I’m trying to figure out the Operation name/Code name for Opapa’s secret mission to Slovenia after the war.

What is an “AGCT score”? It’s listed on the letter of recommendation for Opapa’s promotion.

AGCT is Army General Classification Test, an IQ test to determine intelligence and suitability for leadership. 100 is average; George’s score of 129 is very high.

Great post, Katie. And thanks for the definition, Andrew. The letter from Margit was sad but quite interesting. I had never heard that Arpad had been taken to Germany (I wonder if he really was).