On May 18, 1944, my grandfather, George Gerbner (or Opapa, as I called him), wrote the following words in his journal.

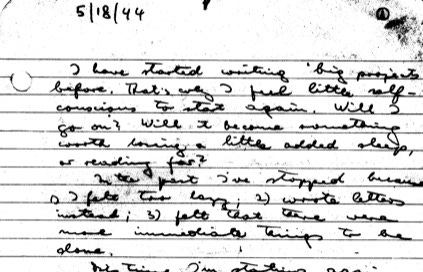

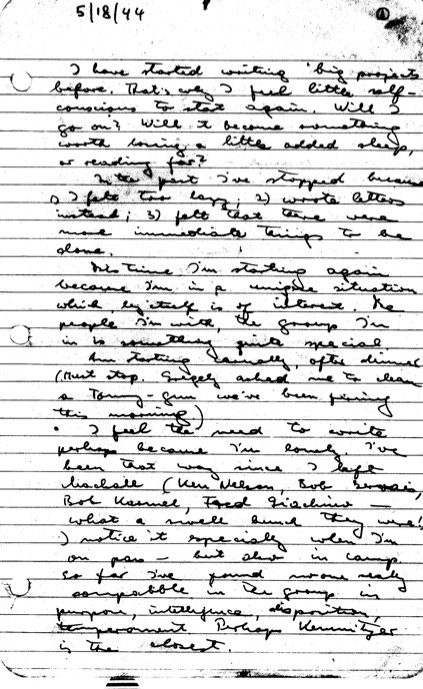

"I have started writing “big projects” before. That’s why I feel [a] little self-conscious to start again. Will I go on? Will it become something worth losing a little added sleep, or reading far? In the past I’ve stopped because 1) I felt too lazy; 2) wrote letters instead; 3) felt that there were more immediate things to be done."

So begins Opapa's diary - at least the portion I have access to right now. Opapa scanned this page, and several other pages from his 1944 diary, into his computer over twenty years ago, in 2005.

In 2005, Opapa had started to write an autobiography. I remember him talking about it. He wanted to called it “Turning Points,” and to focus on a select handful of moments in his life that changed his trajectory in a fundamental way.

This particular page was not a “turning point.” It was a bit more of an existential crisis: “I have started writing 'big projects' before,” he wrote. “That's why I feel [a] little self-conscious to start again.”

It's a side of Opapa I rarely saw: one who had self doubt, who questioned where things were going, who asked: “Will I go on? Will it become something worth losing a little added sleep, or reading far?”

It's a side of Opapa that acknowledged failure: “In the past I've stopped because (1) I felt too lazy; (2) wrote letters instead; (3) felt that there were more immediate things to be done.”

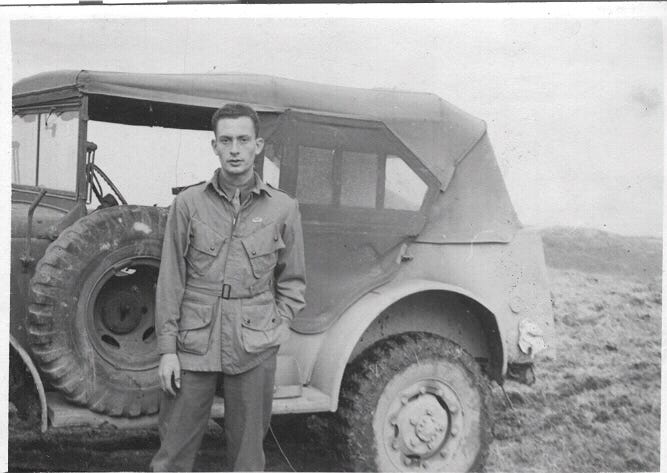

I deeply appreciate seeing this side of Opapa. It's relatable, questioning, and very human. And yet, then I think about where Opapa was when he wrote these words, and the chasm between us reemerges: he was twenty-four years old and had fled Hungary, his homeland, five years before - in 1939. He would never see his father again, though he didn't know that at the time. He had emigrated, alone, to a foreign country, learned a new language, enrolled in University, then joined the military and volunteered for the paratroopers, one of the most dangerous roles in the service. By the time he wrote this entry, he had volunteered yet again for another dangerous venture: to be in an Operational Group for the OSS, the forerunner of the CIA. In May 1944, he was waiting - rather impatiently - to be sent to Europe on an active mission.

The chasm between us is wide: As I write this, I am thirty-nine years old, and I am a History Professor at the University of Minnesota. I've never had to flee my country, and while I've learned new languages, they were never under the duress of forced migration, persecution, or religious oppression. When I was twenty-four - the same age that Opapa when he wrote those pages - I was just beginning a PhD program in History. Opapa had died two years before. My life, while deeply influenced by his (I started a PhD program largely due to his example), never had anywhere close to the level of difficulty that his did.

The chasm between us is wide, and yet we are inexorably connected. I don't know what Opapa's “big project” was when he wrote those words -- maybe to keep a journal? Maybe to write something else? To do something else? But for the past eighteen years, since Opapa died and I knew he had an unfinished autobiography, I've had my own “big project” in mind: to write about his life, about the influence of his research as a Media Studies scholar, and to use those topics to think more broadly about the stories we tell as a society, about the influence of capitalism and technology on our perception of the world, and about the connections between Opapa's life experience -- his first-person experience of fascism, his political commitment to the folk, and their stories, his dedication to fighting the forces in society that he beleived would lead to authoritarian regimes -- to our ongoing struggles as a society today to define what is just, what is true, and what is a story worth telling (and who gets to tell it).

In a way, this “big project” is a simple biography. But I hope it will become more than that. As a historian, I think a lot about the stories we tell about our own past, and how it defines what we believe is important, or worthwhile, about our society today.

This is also an experiment in more directly combining the personal with the political and the historical: this is a biography about a man who had a life that was, simply in itself, worth writing about, but it's also a story about my grandfather who I loved very much, and who is the reason that I, myself, am a historian. The past and the present are more obviously entangled. Unlike the other histories I've told, with this story, I can't ignore that I am, that we are all, personally connected to the past, and that it sets the foundation for how we imagine our future.

So here's to two Big Projects. I hope to learn more about what Opapa's Big Project really was as I write my own, about him, and about the stories he hoped we might all know.